Dr Richard Turnbull is the Director of the Centre for Enterprise, Markets & Ethics (CEME). For more information about Richard please click here.

Dr Richard Turnbull is the Director of the Centre for Enterprise, Markets & Ethics (CEME). For more information about Richard please click here.

Colin Mayer is a distinguished professor at the University of Oxford, former dean of the Said Business School and a Fellow of the British Academy . Throughout his career one of his fields of interests has been the business corporation and at present he is director of the Academy’s research programme into the Future of the Corporation.

However neither the title nor sub-title of the book do justice to its contents. The book is nothing if not ambitious. In examining the business corporation the claim is that “it will take you across history, around the world, through philosophy and biology to business, law and economics, and finance to arrive at an understanding of where we have gone wrong, why, how we can put it right and what specifically we need to do about it”.

The remarkable fact is that I believe he has achieved his aim. The book is wide in scope, has considerable depth and is not superficial. It is well written, interesting to read and draws on a lifetime of research into different aspects of the business organisation.

The book is first a sustained and vigorous attack on Milton Friedman’s claim that the sole social responsibility of business is to increase its profits, subject however to doing so in open and free competitive markets, without deception or fraud, while conforming to the basic rules of the society embodied in law and custom. For Mayer the public have lost trust in business precisely because business has followed Friedman’s advice and put the interests of shareholders above other stakeholders.

In its place he proposes a total reinvention of the corporation. Corporate law should be changed so that each company is required to state its ultimate purpose over and above profit, redefine the responsibilities of directors to deliver these new objectives, develop new measures by which they can be judged and introduce incentives to deliver them.

In exploring the purpose of business Mayer distinguishes between ‘making good’ (such as manufacturing cars, or electrical products) and ‘doing good’ (treating employees well, cleaning up the environment, enhancing the well-bring of communities). The latter has a social public-service element which goes beyond the private interests of the firm’s customers and investors, and even beyond section 172 of the 2006 UK companies Act, which already imposes duties on directors to take into account the interests of stakeholders other than shareholders. As examples of successful and enlightened corporations he mentions with approval “industrial foundations” companies such as Bertelsmann, Bosch, Carlsberg, Tata and John Lewis which are set up as foundations or trusts.

While I admire his ability to explore different dimensions of the business in one book, I have serious problems with his argument.

First, the pursuit of long term profitability is essential if a company wishes to prosper in the long term. Long term profit is a great discipline. This applies not just to publicly quoted companies; it applies equally to private companies, B-corps, partnerships, foundations and trusts. If companies of any kind make losses, capital will drain away and either they get taken over or go bust. This applies to all companies even those which are foundations and trusts. Not only that but long term profitability is a pre-condition of companies doing good: being able to reward employees well, help communities, develop new products and services for customers and invest to protect the natural environment. In this context it is important to distinguish between long term profitability and short term profitability.

The pursuit of short term profitability is bad business. Just recall the financial derivative products created by banks in the feverish boom years leading up to the 2008 crisis which ultimately led to some banks going bust and others being bailed out by governments. This was bad business. British Home Stores was a classic example of short term profit maximization with inadequate investment in the business itself or the pension fund. Again short termism leading to bad business.

Pursuing long term profitability is not just a matter of management getting numbers right. Before they can do that it requires them to set out a vision which makes the firm “a great place to work”, ensures customers recognize value for money in what they buy, becomes known as an ethical organization by the way they conduct business and admired by shareholders for earning a superior long term return to capital.

A second problem with Mayer’s proposals is the sheer complexity of managing the diverse and frequently opposing interests of stakeholders. It is logically impossible to maximize in more than one dimension. If managers have to manage the interests of all stakeholders they need to be able to make meaningful tradeoffs between competing interests. Profit or change in long-term market value is a way of keeping score in the game of business. Michael Jensen and others have shown that in the long term prospective profit maximization and shareholder maximization amount to the same thing. The use by management of a balance scorecard is no better as it ultimately gives no objective way in which to weigh all of the elements in the scorecard to arrive at a single figure.

A third problem with Mayer’s argument is accountability. “Accountability to everyone means accountability to no one”. The author’s proposal is a revolutionary re-definition of property rights within a modern corporation to make it “trustworthy” but to whom is the board of this new “trustworthy” corporation responsible? And what are the rights of ownership over the funds invested in the business? Already in the US the number of publicly traded companies quoted on exchanges has roughly halved over the past 25 years. One reason is the increasing cost of regulation: another is the availability of private equity finance. If Mayer’s proposals were ever to be implemented they would constitute a major disincentive for companies to raise capital through the public markets and only accelerate the decline in stock market listings.

In Mayer’s proposal shareholders would become providers of capital to business rather than owners of the business. The general public have never had a great trust in business which is why ever since the Industrial Revolution governments have stepped in to control business through laws passed by parliament, regulation, mutualisation, nationalization and state ownership. Mayer’s proposals will downgrade the existing well defined ownership rights which exist in publicly traded companies and replace them with a form of ‘social’ decision making in which the leadership of the company is answerable to trustees but shielded from competition in the market place through take over bids. A sure way to create inefficiency.

In this respect these proposals are a far cry from an exercise in academic research, more a political statement. Far from having no objection to the existence of ‘trustworthy’ corporations as one of many different forms of corporate ownership, I welcome them. In terms of corporate structures let a hundred flowers bloom. If the author was making a case for the idea of ‘Industrial corporation’, fine. However he is doing more than that. He is making the case for eroding private property rights and restricting what companies can do, which is as much a political statement as one based on objective analysis.

“Prosperity: better business makes the greater good” by Colin Mayer was published in 2018 by Oxford University Press (ISBN: 978-0-1988240-08). 288pp.

Lord Griffiths is the Chairman of CEME. For more information please click here.

Colin Mayer is a distinguished professor at the University of Oxford, former dean of the Said Business School and a Fellow of the British Academy . Throughout his career one of his fields of interests has been the business corporation and at present he is director of the Academy’s research programme into the Future of the Corporation.

However neither the title nor sub-title of the book do justice to its contents. The book is nothing if not ambitious. In examining the business corporation the claim is that “it will take you across history, around the world, through philosophy and biology to business, law and economics, and finance to arrive at an understanding of where we have gone wrong, why, how we can put it right and what specifically we need to do about it”.

The remarkable fact is that I believe he has achieved his aim. The book is wide in scope, has considerable depth and is not superficial. It is well written, interesting to read and draws on a lifetime of research into different aspects of the business organisation.

The book is first a sustained and vigorous attack on Milton Friedman’s claim that the sole social responsibility of business is to increase its profits, subject however to doing so in open and free competitive markets, without deception or fraud, while conforming to the basic rules of the society embodied in law and custom. For Mayer the public have lost trust in business precisely because business has followed Friedman’s advice and put the interests of shareholders above other stakeholders.

In its place he proposes a total reinvention of the corporation. Corporate law should be changed so that each company is required to state its ultimate purpose over and above profit, redefine the responsibilities of directors to deliver these new objectives, develop new measures by which they can be judged and introduce incentives to deliver them.

In exploring the purpose of business Mayer distinguishes between ‘making good’ (such as manufacturing cars, or electrical products) and ‘doing good’ (treating employees well, cleaning up the environment, enhancing the well-bring of communities). The latter has a social public-service element which goes beyond the private interests of the firm’s customers and investors, and even beyond section 172 of the 2006 UK companies Act, which already imposes duties on directors to take into account the interests of stakeholders other than shareholders. As examples of successful and enlightened corporations he mentions with approval “industrial foundations” companies such as Bertelsmann, Bosch, Carlsberg, Tata and John Lewis which are set up as foundations or trusts.

While I admire his ability to explore different dimensions of the business in one book, I have serious problems with his argument.

First, the pursuit of long term profitability is essential if a company wishes to prosper in the long term. Long term profit is a great discipline. This applies not just to publicly quoted companies; it applies equally to private companies, B-corps, partnerships, foundations and trusts. If companies of any kind make losses, capital will drain away and either they get taken over or go bust. This applies to all companies even those which are foundations and trusts. Not only that but long term profitability is a pre-condition of companies doing good: being able to reward employees well, help communities, develop new products and services for customers and invest to protect the natural environment. In this context it is important to distinguish between long term profitability and short term profitability.

The pursuit of short term profitability is bad business. Just recall the financial derivative products created by banks in the feverish boom years leading up to the 2008 crisis which ultimately led to some banks going bust and others being bailed out by governments. This was bad business. British Home Stores was a classic example of short term profit maximization with inadequate investment in the business itself or the pension fund. Again short termism leading to bad business.

Pursuing long term profitability is not just a matter of management getting numbers right. Before they can do that it requires them to set out a vision which makes the firm “a great place to work”, ensures customers recognize value for money in what they buy, becomes known as an ethical organization by the way they conduct business and admired by shareholders for earning a superior long term return to capital.

A second problem with Mayer’s proposals is the sheer complexity of managing the diverse and frequently opposing interests of stakeholders. It is logically impossible to maximize in more than one dimension. If managers have to manage the interests of all stakeholders they need to be able to make meaningful tradeoffs between competing interests. Profit or change in long-term market value is a way of keeping score in the game of business. Michael Jensen and others have shown that in the long term prospective profit maximization and shareholder maximization amount to the same thing. The use by management of a balance scorecard is no better as it ultimately gives no objective way in which to weigh all of the elements in the scorecard to arrive at a single figure.

A third problem with Mayer’s argument is accountability. “Accountability to everyone means accountability to no one”. The author’s proposal is a revolutionary re-definition of property rights within a modern corporation to make it “trustworthy” but to whom is the board of this new “trustworthy” corporation responsible? And what are the rights of ownership over the funds invested in the business? Already in the US the number of publicly traded companies quoted on exchanges has roughly halved over the past 25 years. One reason is the increasing cost of regulation: another is the availability of private equity finance. If Mayer’s proposals were ever to be implemented they would constitute a major disincentive for companies to raise capital through the public markets and only accelerate the decline in stock market listings.

In Mayer’s proposal shareholders would become providers of capital to business rather than owners of the business. The general public have never had a great trust in business which is why ever since the Industrial Revolution governments have stepped in to control business through laws passed by parliament, regulation, mutualisation, nationalization and state ownership. Mayer’s proposals will downgrade the existing well defined ownership rights which exist in publicly traded companies and replace them with a form of ‘social’ decision making in which the leadership of the company is answerable to trustees but shielded from competition in the market place through take over bids. A sure way to create inefficiency.

In this respect these proposals are a far cry from an exercise in academic research, more a political statement. Far from having no objection to the existence of ‘trustworthy’ corporations as one of many different forms of corporate ownership, I welcome them. In terms of corporate structures let a hundred flowers bloom. If the author was making a case for the idea of ‘Industrial corporation’, fine. However he is doing more than that. He is making the case for eroding private property rights and restricting what companies can do, which is as much a political statement as one based on objective analysis.

“Prosperity: better business makes the greater good” by Colin Mayer was published in 2018 by Oxford University Press (ISBN: 978-0-1988240-08). 288pp.

Lord Griffiths is the Chairman of CEME. For more information please click here.

A PDF copy of this paper can be accessed here.

The advent of Generative AI is challenging and redefining the world of work. While exacting data on its impact remain at a nascent stage, a growing number of private firms and research organisations have been quick to impart their early predictions. McKinsey & Co. estimates that Generative AI could add as much as $4.4 trillion to the global economy annually, leading to profound changes in the anatomy of work, with an increase in both augmentation and automation capabilities of individual workers across all industries.[1] Goldman Sachs believes that Generative AI could raise global GDP by as much as 7% with two-thirds of current occupations being affected by automation.[2] At the macro level AI is poised to reshape the strengths of nation-state economies. Research conducted by Oxford University and CITI Bank found that ‘The comparative advantage of rich nations will increasingly lie in the early stages of product life cycles — exploration and innovation rather than execution or production — and this will make up a bigger portion of total employment. […] Without innovation, progress and productivity will stall’.[3]

In September 2023 Microsoft launched ‘Copilot 365’, an AI-driven digital assistant that integrates Office applications such as Word, Excel and PowerPoint to enable the user to harness the capabilities of AI within their workflow. Copilot and other AI agents such as Google’s ‘Gemini’ aim to combine the use of Large Language Models (LLMs) and user generated data to greatly enhance productivity. Microsoft Chairman and CEO Satya Nadella said that ‘[Copilot] marks the next major step in the evolution of how we interact with computing, which will fundamentally change the way we work and unlock a new wave of productivity growth. […] With our new copilot for work, we’re giving people more agency and making technology more accessible through the most universal interface — natural language’.[4]

These potentially seismic changes urge us to reconsider the fundamental nature of work. They force us to step back and ask how ought humanity shape its future relationship with work. This implicitly raises wider questions of purpose, meaning and a sense of calling that pervades the mere temporal dimension of work. From a Judaeo-Christian perspective it seeks a re-evaluation of the gift and place of human agency and responsibility within creation.

The argument of this paper is therefore twofold. First, we point out that that all technological advancements, including Generative AI, should be harnessed for the benefit and enhancement of humanity. This applies in particular to work but should not be excluded from other spheres of human endeavour such as leisure or recreation. Second, we point out that, while most technological advancements are valuable, a careful and persistent degree of discernment needs to be applied in minimising the novel risks brought on by Generative AI. A central concern here is the capacity for misuse of AI (with all the various facets that that entails), as well as the long-term risk that it presents of a destructive and dehumanising effect on its users.

Defining the Terms

It is worth starting with a brief conceptual analysis of some of the key terms. What do we mean by ‘work’? How are we to delineate a ‘humanising’ versus ‘dehumanising’ effect on work? Indeed, are we mistaken in assuming any intrinsic value of work in the first place? These are all pertinent questions that require much thought and attention.

In his monograph on Recovering a Theology of Work, Revd Dr Richard Turnbull rightly points out that work ’…is not a static concept’.[5] Work evolves in tandem with the ability of humans to learn, pursue and engage with it, which implies an ongoing relational change in both skill and knowledge. This creative ability is, for the Christian theologian, a reflection of the Imago Dei that is fundamental to all of humanity. Darrell Cosden, who wrote extensively on the theology of work acknowledges that ’work is a notoriously difficult concept to define’.[6] Cosden views human work as ’a transformative activity essentially consisting of dynamically interrelated instrumental, relational, and ontological dimensions’.[7] Work is therefore a multifaceted concept.

If we step back for a moment and consider a more utilitarian interpretation we find some rather crude definitions of work. The Cambridge dictionary sees it as ’an activity, such as a job, that a person uses physical or mental effort to do, usually for money’.[8] In pure physics work is ’the transfer of energy by a force acting on an object as it is displaced’.[9] This apparent dichotomy leads us to (at least), two broad and distinct dimensions of work: 1. The physical or mental activity that usually results in quantifiable economic activity; 2. Work in relation to meaning (or semantics), the presence of a personal calling and a higher purpose that serves as an ultimate goal.

Attempts to categorise the term ‘humanising’ are also likely to encounter an additional array of definitional challenges. Some dictionaries see it as ‘representing (something) as human: to attribute human qualities to (something)’,[10] others define it as ‘the process of making something less unpleasant and more suitable for people’.[11] The common denominator in attempting to describe ‘humanising’ is the intention to give something qualities that make it suitable for humans to use and understand – an effort which in and of itself no doubt suffers from a degree of subjectivity.

The last major term that we will attempt to define is ‘Generative Artificial Intelligence (AI)’. I have written elsewhere about the concept of intelligence and how it fits within AI, so a detailed discussion on the matter will not be included here. However, what is worth mentioning is that by ‘Generative AI’ we are referring to complex yet narrow AI systems that currently exist or at most are likely to emerge within the short to medium term (3-5 years). By ‘generative’ we are referring to AI systems that not only learn from new data but generate interpretable results based on said data – this includes LLMs such as ChatGPT3/4, LaMDA, Google Gemini and so on.

The Impact of Generative AI

There are competing narratives as to which technological changes of the modern era bear the greatest impact on work and productivity. The British Agricultural revolution of the 17th and 18th centuries saw a dramatic increase in crop yields and agricultural output which resulted in the population of England and Wales almost doubling from 5.5 million in 1700 to over 9 million by the end of the century.[12] The arrival of the steam engine in the second half of the 18th century and the subsequent mechanisation of labour sparked the first and second Industrial Revolutions. The change to the nature and purpose of work during this time was fundamental. Europe moved from a largely agrarian-based society to one that was driven by mass production, standardisation and the development of new skills and abilities in manufacturing and scientific discovery.

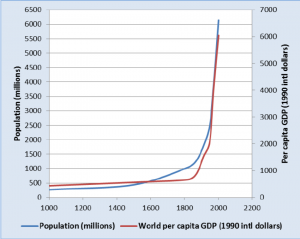

One remarkable chart worth revisiting is illustrated in the adjacent figure.[13] For over 1,800 years GDP per capita remained largely flat – and only changed in the late 19th century when both GDP per capita and global population experienced a sudden and unprecedented jump in both trajectory and scale. The change was overwhelmingly attributed to the transition of a workforce that had previously been accustomed to hand manufacturing and production to becoming almost entirely machine-driven. This in turn, allowed for more effective and precise tools, a greater understanding of chemicals and alloys, and widespread availability of these to workers that previously relied solely on manual labour. Some economic historians such as Paul Bouscasse et al. (2021) estimate that the Industrial Revolution quadrupled average productivity by each decade, from around 4% up until the 1810s to over 18% from there onwards.[14]

One remarkable chart worth revisiting is illustrated in the adjacent figure.[13] For over 1,800 years GDP per capita remained largely flat – and only changed in the late 19th century when both GDP per capita and global population experienced a sudden and unprecedented jump in both trajectory and scale. The change was overwhelmingly attributed to the transition of a workforce that had previously been accustomed to hand manufacturing and production to becoming almost entirely machine-driven. This in turn, allowed for more effective and precise tools, a greater understanding of chemicals and alloys, and widespread availability of these to workers that previously relied solely on manual labour. Some economic historians such as Paul Bouscasse et al. (2021) estimate that the Industrial Revolution quadrupled average productivity by each decade, from around 4% up until the 1810s to over 18% from there onwards.[14]

Large-scale industrialisation and the rise of the mechanised factory system created fertile ground for what would later become the digital revolution (i.e. the Third Industrial Revolution). The middle of the 20th century saw the arrival of the first transistor which not only paved the way for modern computing, it more fundamentally enabled the digitalisation of information. This marked a major change in the way in which information is stored and shared, and perhaps unsurprisingly, at least in retrospect, also brought profound changes for the world of work. The first through third Industrial Revolutions represent magnificent events of human advancement that altered the course of history in ways that make the absence of their fruits in contemporary life hard to imagine. Therefore, how would Generative AI fit within such a paradigm?

The scholastic body of research in this area is embryonic. The ‘Fourth Industrial Revolution’ or ‘Industry 4.0’ coined back in 2013 by former German Chancellor Angela Merkel foresaw a future where the collective power of technologies such as AI, 3D Printing, Virtual Reality (VR), the Internet of Things (IoT), and others could be integrated and used within a (predominantly) unified system.[15] Over a decade later this holistic vision has yet to fully materialise. What we are currently seeing are many of these technologies being largely used in silos rather than fully integrated systems (with a few exceptions such as smart homes). In 2020 a KPMG report found that less than half of business leaders understood what the ’fourth industrial revolution’ meant, with online searches of the term having peaked in 2019 and trending downward ever since.[16]

On one level the prophecies of the Fourth Industrial Revolution have yet to be fulfilled. Current research into the impact of AI is therefore reliant upon scarce present data and future predictions that are, more often than not, overhyped and peppered with unlikely outcomes. One more robust piece of research has been an intercollegiate effort between academics at the universities of Leeds, Cambridge and Sussex, which found that 36% of UK employers have invested in AI-enabled technologies but only 10% of employers who hadn’t already invested in AI were planning to do so in the next two years.[17] Commenting on the research, Professor Mark Stuart, Pro Dean for Research and Innovation at Leeds University Business School said that,

’A mix of hope, speculation, and hype is fuelling a runaway narrative that the adoption of new AI-enabled digital technologies will rapidly transform the UK’s labour market, boosting productivity and growth. However, our findings suggest there is a need to focus on a different policy challenge. The workplace AI revolution is not happening quite yet. Policymakers will need to address both low employer investment in digital technologies and low investment in digital skills, if the UK economy is to realise the potential benefits of digital transformation.’[18]

These apparent roadblocks will require a concerted effort on behalf of employers and employees to actively seek and develop new skills that will give organisations the capabilities required to meaningfully integrate AI systems into their workflows. As has been the case with the industrial revolutions of the past, new technologies invariably necessitate new knowledge and training. AI Prompt Engineering is an interesting example of this. Although Large Language Models (LLMs) are built to operate via NLP (Natural Language Processing), they still require specialised training when dealing with more complex challenges or troubleshooting errors. A ‘Prompt Engineer’ in this sense is a trained professional that creates ‘prompts’ (usually in the form of text), to test and evaluate LLMs such as ChatGPT.[19] Thus, a well-trained prompt engineer can extract and gain far more from LLMs than the average user.

More importantly, the skills and capabilities gap between AI systems and the end-user need to be bridged in a manner that allows for the concurrent growth of the technology as well as the flourishing of the workforce. This is all the more pertinent when we are talking about a workforce that is predicted to become increasingly reliant on AI. What generative AI has achieved thus far is to fuel a creative springboard that enabled a wider audience to imagine the possibilities (and risks) of AI tools: ranging from relatively banal features such as improved email spam filtering to uncovering disease-fighting antibodies. A report by the International Data Corporation (IDC) estimated that the use of conversational AI tools is expected to grow worldwide by an average of 37% from 2019 to 2026.[20] With the accelerated growth of Microsoft’s ChatGPT, Google’s Bard as well as other tech giants joining the conversational AI race, it is reasonable to expect that this figure may end up being higher.

Yet we do not know exactly what impact this will have upon work. There have been some early studies and working papers that suggest that AI tools are having a positive effect on employee productivity. The National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) recently published a paper by Erik Brynjolfsson, Danielle Li & Lindsey R. Raymond which looked at a case study of 5,179 customer support agents using AI tools. The report found that,

‘Access to the tool increases productivity, as measured by issues resolved per hour, by 14% on average, including a 34% improvement for novice and low-skilled workers but with minimal impact on experienced and highly skilled workers. We provide suggestive evidence that the AI model disseminates the best practices of more able workers and helps newer workers move down the experience curve. In addition, we find that AI assistance improves customer sentiment, increases employee retention, and may lead to worker learning. Our results suggest that access to generative AI can increase productivity, with large heterogeneity in effects across workers.’[21]

It appears therefore that while there is an overall increase in productivity, a key factor in its dispersion is dependent upon the varying degrees of employee experience and skill level, with those at the lower end of the spectrum likely to benefit more that those at the top. Another study led by Shakked Noy and Whitney Zhang from MIT looked at an empirical analysis of business professionals who wrote a variety of business documents with the assistance of ChatGPT. The study found that of the 444 participants, those that used ChatGPT were able to produce a deliverable document within 17 minutes compared to 27 minutes for those who worked without the assistance of ChatGPT.[22] This translates to a productivity improvement of 59%. What is perhaps more remarkable is that the output quality also increased: blind independent graders examined the documents and those written with the help of ChatGPT achieved an average score of 4.5 versus 3.8 for those without.[23] A third preliminary study looked at the impact of ‘GitHub Copilot’, an AI tool used to assist in computer programming. The paper found that programmers who used GitHub Copilot were able to complete a job in 1.2 hours, compared to 2.7 hours for those who worked alone. In other words, task throughput increased by 126% for developers who used the AI tool.[24]

Pursuing a Theology of Work

This provokes some wider questions surrounding morality, AI and work. One pertinent question here is not just a matter of can we use AI but rather how ought we to use AI? Indeed, how are we to best integrate AI in manner that reaps the rewards and minimises the risks? If we consider the Judaeo-Christian perspective, the obligatory prerequisite to answering these questions is a scriptural understanding of the act and role of work.

In the Old Testament we find several fundamental passages in relation to work. The first and perhaps most widely cited is Genesis 1:28 and 2:15 where humanity is called to ‘Be fruitful and increase in number; fill the earth and subdue it. Rule over the fish in the sea and the birds in the sky and over every living creature that moves on the ground. […] The Lord God took the man and put him in the Garden of Eden to work it and take care of it.’[25] The command here is not just one of stewardship over creation, but a calling to reflect through human capacities that which is teleologically divine: the ability to order, create, tend to, and indeed destroy (within the premise of the fall).

God himself is portrayed as a worker: ’In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth’ (Gen. 1:1), and then in Genesis 1:27 we find that God ’created man in his own image’.[26] In this sense human work is fundamentally ’…derived from the principle of God’s work in creation’.[27] While humanity is called to mimic God’s creative pursuit, it also has the responsibility to protect and care for the gift that is creation and everything found within it. Genesis 2:15 portrays the garden as an adequate place where man can fulfil his duty and calling of work. David Atkinson in his commentary usefully points out that ‘…work is not simply to be identified with paid employment. Important as paid work is in our society, both in providing necessary conditions for adequate living standards, and in giving a person a sense of worth in his or her creativity, it is the creative engagement with the world on behalf of God that is the really significant thing’.[28] This rather Barthian perspective gives significance to work in as much as it represents a conscious partaking in the establishment of God’s kingdom through Christ. The objective is, according to Barth, ‘…the centre of God’s activity. [..] [so] the centre of our human actions as Christians must be to reflect this focus on the kingdom of God’.[29] Work therefore encapsulates the temporal and the metaphysical. Human action is not merely a bystander to the cosmic order of events but an active partaker in shaping the journey. The Genesis account of creation therefore does not delineate between secular and pious work – all work in the garden carries some degree of spiritual value. It is important to note that the distinction between the sacred and the secular in the first place can only be made in light of the fall.

This raises another key dimension in developing a theology of work, that is, the notion of calling and vocation. For Martin Luther there are two kingdoms: the temporal and the eternal. Human endeavour operates entirely within the temporal but the tension between good and evil (or sin) cuts through and is present in both, making the struggle omnipresent. The act of human calling and vocation in the temporal therefore becomes as important and relevant as it is in the eternal. There is a continuous interplay between the two, as Richard Turnbull notes: “there is no dualism here in Luther. Vocation and calling, ethics and behaviour are the ways God is served in the temporal kingdom”.[30]

If we turn to the New Testament we find a series of examples where so-called ‘secular’ work is used to advance the heavenly kingdom. In Acts Chapter 16 we are introduced to Lydia of Thyratira, a businesswoman in what was considered those days to be expensive clothing or ‘purple cloth’ (verse 14). We are told that Lydia persuaded the apostles and used her earned resources to care and provide for Paul and Silas: ‘If you consider me a believer in the Lord,’ she said, ‘come and stay at my house’ (verse 15). Paul himself, though highly educated in the Hebrew law, maintained his work as a tentmaker (Acts 18:3) and used it to not only financially support his ministry but also to minister to others through it:

‘I coveted no one’s silver or gold or apparel. You yourselves know that these hands ministered to my necessities, and to those who were with me. In all things I have shown you that by so toiling one must help the weak, remembering the words of the Lord Jesus, how he said, “It is more blessed to give than to receive.”’ (Acts 20:33-35, RSV)

As a more anecdotal observation, it is interesting to see how Paul, though a scholar, never found himself too proud to undertake manual labour. That was likely driven by his profound understanding of what true Christological self-sacrificial love and service entails – his life as presented in the scriptures embodies it fully.

Peter, Andrew, James and John were the first disciples called by Jesus in Matthew 4:18–22. By most historical accounts they were ordinary fishermen operating within a highly competitive fishing environment that were the shores of Galilee in the 1st Century A.D. It is reasonable to assume that they possessed some degree of business acumen in budgeting, preparing orders, managing stocks and so on. Indeed, Jesus himself worked as a carpenter in his family business (Mark 6:3) and one can imagine that Joseph (and likely Jesus himself) had to utilise their skills and knowledge in budgeting, drawing projects, analysing space, preparing materials and fulfilling orders to clients – there is no suggestion in scripture that this was a pro bono affair.

Neither Jesus, nor any of the disciples shied away from what would today be labelled as ‘secular work’. Quite the contrary, they embodied work as: 1. An integral part of their calling before God in the temporal; and 2. A fulfilment of their God-given gifts and abilities in utilising and developing the skills needed to carry out the work. Indeed, Christ vividly illustrated the implications of this aspect in the Parable of the Talents found in Matthew 25:14–30 and Luke 19:11–27.

Conclusions: Towards a collaborative theology of work and AI?

In the introduction we mentioned the necessity and overarching aim that all technological advancements, including Generative AI, should be harnessed for the benefit and enhancement of humanity. This applies in particular to work but also to other spheres of human activity such as family time or recreation. It is also important to note that great care and discernment needs to be applied in minimising the novel risks posed by Generative AI, such as an unhealthy reliance on the technology, disinformation, fraud, and so on. Discernment in this case refers to uncovering the right way of action amidst uncertainty.

We have also seen how Judaeo-Christian teaching places the concept of Work as a key part of what it means to be made in the image of God and to actively partake in the eschatological realisation of creation. If work therefore represents an integral element of Christ’s redemptive transformation of the individual (and indeed the world), how does AI fit within this paradigm?

One possibility is arguing in favour of AI as a tool or digital aid to humanity. Within a Judaeo-Christian framework the role of AI ought to be one that contributes to humanity’s holistic development, be that spiritual, economic or scientific. Central to this overarching view of humanity is the promotion and protection of human dignity – a core principle of Catholic Social Thought (alongside the common good, solidarity and subsidiarity). If we are to see AI as a tool for human advancement and productivity, then it becomes part of an economic system that ought to be conducive to upholding human dignity. As Mons. Martin Schlag rightly points out, ‘Economic growth, material prosperity and wealth are without doubt necessary conditions for a life in dignity and freedom but they are not sufficient’.[31] In this sense, AI should bring economic benefits whist not representing a hindrance to spiritual growth (for instance, the creation of ‘false idols’ or idolatry found in Exodus 20:3, Matthew 4:10, Luke 4:8), or indeed the promotion of scripturally antagonistic values such as greed, deceit, egotism or malice of any kind.

On a more practical level, the concrete steps of integrating such guideposts in AI development will have to come, at least to some extent, from the programme creators themselves. However, it is also equally important to emphasise a degree of personal responsibility that will invariably become necessary when dealing with powerful open-ended AI systems.

AI is then best understood as a gift of human creativity, yet one that can sometimes lead to unpredictable outcomes (such as black box scenarios within LLMs). Digital AI assistants therefore need to be utilised in a manner that is conducive to a harmonious synergy between work and AI tools. The aim here is to augment and transform work rather than replace it. Digital AI assistants ought to be just that: assistants built upon a foundation of ethical values that contribute to human dignity and flourishing. Bill Gates wrote in a recent article that, ‘…advances in AI will enable the creation of a personal agent. Think of it as a digital personal assistant: It will see your latest emails, know about the meetings you attend, read what you read, and read the things you don’t want to bother with. This will both improve your work on the tasks you want to do and free you from the ones you don’t want to do.’[32] In March 2023 Pope Francis said, ‘I am convinced that the development of artificial intelligence and machine learning has the potential to contribute in a positive way to the future of humanity. […] I am certain that this potential will be realized only if there is a constant and consistent commitment on the part of those developing these technologies to act ethically and responsibly.’[33]

The future of AI and work is important not just because of its bearing on the individual but also because of its capacity to influence societal transformations. The advent of the personal computer (PC) for instance sparked profound changes in the world of work in the 1980s-1990s. A human-centric vision of AI will require a concerted effort on the part of all parties (developers and users) to ensure that the implementation represents an enrichment to human life – and as we have seen, considerations of the meaning, value and purpose of work are of fundamental importance. Such an approach would strengthen humanity’s position to reap the rewards and mitigate the risks in a myriad of areas – from creative agency and productivity to medical and scientific discovery.

Andrei E. Rogobete is Associate Director at the Centre for Enterprise, Markets & Ethics. For more information about Andrei please click here.

[1] ‘The economic potential of generative AI: The next productivity frontier’, McKinsey & Co., https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/mckinsey-digital/our-insights/the-economic-potential-of-generative-ai-the-next-productivity-frontier

[2]‘Generative AI could raise global GDP by 7%’, Goldman Sachs, https://www.goldmansachs.com/intelligence/pages/generative-ai-could-raise-global-gdp-by-7-percent.html

[3] ‘TECHNOLOGY AT WORK v6.0 The Coming of the Post-Production Society’, Oxford University Martin School, June 2021, https://www.oxfordmartin.ox.ac.uk/downloads/academic/Technology-at-Work-6.pdf

[4] ‘Introducing Microsoft 365 Copilot – your copilot for work’, Official Microsoft Blog, 16th March 2023, https://blogs.microsoft.com/blog/2023/03/16/introducing-microsoft-365-copilot-your-copilot-for-work/

[5] Turnbull, Richard, Work as Enterprise: Recovering a Theology of Work, Oxford: The Centre for Enterprise, Markets & Ethics, 2018, p. 7

[6] Ibid.

[7] Cosden, Darrell, A Theology of Work: Work in the New Creation, Milton Keynes: Paternoster theological monographs, 2006, https://www.bu.edu/cpt/2013/10/03/theology-of-work-by-darrell-cosden/

[8] ‘Work’, Cambridge Dictionary, https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/work

[9] ‘Work – The Scientific Definition’, University of Iowa Pressbooks, https://pressbooks.uiowa.edu/clonedbook/chapter/work-the-scientific-definition/

[10] ‘Humanise’, Merriam-Webster Dictionary, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/humanize

[11] ‘Humanisation’, Cambridge Dictionary, https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/humanization

[12] Richards, Denis; Hunt, J.W., An Illustrated History of Modern Britain: 1783–1980 (3rd ed.), Hong Kong: Longman Group, 1983, p. 7.

[13] Slaus, IvoI & Jacobs, Garry. ‘Human Capital and Sustainability’, Sustainability. (2011). Vol.3(1): 97-154.

[14] Bouscasse, Paul, Emi Nakamura, & Jón Steinsson, ‘When Did Growth Begin? New Estimates of Productivity Growth in England from 1250 to 1870’, NBER Working Paper Series, March 2021, https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w28623/revisions/w28623.rev0.pdf

[15] ‘Industrie 4.0’, National Academy of Science and Engineering, https://en.acatech.de/project/industrie-4-0/

[16] Markoff, Richard; Seifert, Ralf; ‘Why the promised fourth industrial revolution hasn’t happened yet’, The Conversation, 27th February 2023, https://theconversation.com/why-the-promised-fourth-industrial-revolution-hasnt-happened-yet-199026

[17] University of Leeds, ‘Workplace AI revolution isn’t happening yet,’ survey shows’, 4th July 2023 https://www.leeds.ac.uk/news-business-economy/news/article/5341/workplace-ai-revolution-isn-t-happening-yet-survey-shows

[18] Ibid.

[19] Yasar, Kinza, ‘AI prompt engineer’, TechTarget, https://www.techtarget.com/searchenterpriseai/definition/AI-prompt-engineer

[20] Sutherland, Hayley; Schubmehl, David; ‘Worldwide Conversational AI Tools and Technologies Forecast, 2022-2026’, International Data Corporation (IDC), July 2022.

[21] Brynjolfsson, Erik; Li, Danielle; Raymond, Lindsey; ‘Generative AI at Work’, NBER Working Paper Series, November 2023, https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w31161/w31161.pdf

[22] Nielsen, Jakob; ‘ChatGPT Lifts Business Professionals’ Productivity and Improves Work Quality’, Nielsen Norman Group, 2nd April 2023, https://www.nngroup.com/articles/chatgpt-productivity/

[23] Ibid.

[24] Nielsen, Jakob; ‘AI Tools Make Programmers More Productive’, Nielsen Norman Group, 16th July 2023, https://www.nngroup.com/articles/ai-programmers-productive/

[25] The Holy Bible, (NIV Translation)

[26] Genesis 1:27, The Holy Bible, (NIV Translation)

[27] Turnbull, Richard, Work as Enterprise: Recovering a Theology of Work, Oxford: The Centre for Enterprise, Markets & Ethics, 2018, p. 16

[28] Atkinson, David; The Message of Genesis, Cambridge: IVP, 1990, p. 61

[29] Ibid., p. 60

[30] Turnbull, Richard, Work as Enterprise: Recovering a Theology of Work, Oxford: The Centre for Enterprise, Markets & Ethics, 2018, p. 26

[31] Shlag, Martin; Business in Catholic Social Thought, Oxford: The Centre for Enterprise, Markets & Ethics, 2016, p. 22

[32] Gates, Bill; ‘The Age of AI has begun’, Gates Notes – The Blog of Bill Gates, 21st March 2023, https://www.gatesnotes.com/The-Age-of-AI-Has-Begun

[33] Lubov, Deborah Castellano; ‘Pope Francis urges ethical use of artificial intelligence’, Vatican News, 27th March 2023, https://www.vaticannews.va/en/pope/news/2023-03/pope-francis-minerva-dialogues-technology-artificial-intelligenc.html

When we consider the evident benefits of capitalism in its capacity to generate wealth and lift people out of poverty, and contrast this with the failure of attempts to implement socialism, we might ask ourselves why Marxist thought continues to exercise such influence. This is the question with which Tibor Rutar (Assistant Professor at the University of Maribor) opens Capitalism for Realists. His answer is that the appeal of Marxism appears to lie in its theoretically grounded criticisms of capitalism – criticisms that might very well ring true for those who do not directly feel its benefits. Nevertheless, the author points out, the more poignant criticisms of capitalism are not unique to Marxism and might just as easily be reached from other theoretical positions. Accordingly, the aim of this book is not to offer an ideologically driven attack on capitalism – or necessarily to defend it – but to provide a balanced reckoning based on the available (quantitative) evidence. What follows is a fairly involved and detailed examination of the statistical information relating to the debates that surround capitalism in connection with issues such as wealth and poverty, inequality, exploitation, morality and politics.

The first chapter considers the origins of capitalism and in place of cultural explanations such as Weber’s ‘Protestant Ethic’ thesis, offers a materialist account that attributes the emergence of capitalism in England to the massive population decline caused by the Black Death, a situation that gave rise to a market for land leases and labour as land became vacant and landowners sought to retain peasants on their demesnes in order to mitigate economic losses. Thus, whatever the role of ‘ideational’ changes such as the Protestant Reformation, it was English material conditions that ‘set the scene’ for the transition to capitalism. The argument in this chapter is compelling and interesting to follow, but I was left wondering what capitalism is taken to be in the author’s view. As a very broad term, it can often encompass vastly different phenomena – a point that the author himself makes about ‘neoliberalism’ – and it would have been useful from the outset to have a definition of what the author was seeking to analyse throughout the book.

Subsequent chapters consider the criticisms commonly levelled at capitalism. In the chapter on poverty, inequality and exploitation, the author points out that capitalism has reduced extreme poverty but does not distribute the wealth that it creates equally. While the picture painted by the data is not uniform, Rutar’s analysis suggests that over longer periods of time, inequalities in wealth within countries are increasing. However, he is quick to highlight the fact that the growing wealth of the rich does not mean that the poor are getting poorer, though he does urge us to remember that rising inequalities can and do result in various societal problems which should not be ignored. While rejecting the classical Marxist position on exploitation, the author’s suggestion is that some (wage) exploitation is likely to exist in any economic system and in capitalist economies cannot be eliminated by market competition for labour alone. However, a difficulty with the treatment of this subject is that it is not quite clear what Rutar intends by ‘exploitation’: whether the mere fact of companies paying employees less than the full value of their labour when estimated as a financial contribution to the company, or the more sinister, deliberate attempt to suppress wages in order to maximise profits. The former is open to question as a definition of exploitation, since it is unclear whether the financial contribution of workers can be calculated with any accuracy; the latter more obviously runs counter to our ideas of a just wage.

The following chapter considers ‘neoliberalism’, a term that is often used pejoratively but, as the author rightly states, lacks any clear definition. In view of this, his focus is on those generally accepted features of neoliberalism that lend themselves to empirical investigation, such as support for free markets and modest welfare states. The analysis leads to the view that as the world has become more neoliberal over the last forty years, poverty has been reduced and material prosperity increased, with no apparent fall in overall government spending, no destruction of welfare provision and broad stability (or increases) in tax revenues. Moreover, capitalist societies appear to be conducive to the emergence and development of democratic orders. Thus, contrary to the charges levelled at it by its critics, neoliberalism has surely been an economic success.

I was particularly interested in the chapter on morality, which the author begins by contrasting the ‘classical’ view that commerce leads to gentler manners, greater co-operation and trust, with the anti-capitalist position that capitalism, as a system based on competition and profit, surely appeals to our most selfish tendencies, eroding trust and leading us to see others as mere means. From surveying the existing evidence, Rutar concludes that capitalist societies are certainly not inimical to the emergence of more moral conduct and in fact show greater levels of trust, whilst exposure to market competition appears to boost co-operation and fairness. At the state level, the data suggests an incompatibility between economic liberalisation and human rights abuses, and that wealthier states with complex economies characteristic of capitalism are less likely to suffer political coups.

It is clear, given his focus on measurable, quantifiable phenomena, that what the author is (understandably) concerned with in this chapter is not morality understood as personal virtue or vice, but what we might call pro-social attitudes and behaviours. Indeed, the book does not take up questions of value, except insofar as it is implied that capitalist economics can be said to embody a set of values, such as a belief in property rights and economic liberty, and a conviction that material prosperity is a ‘good thing’ for all. However, if capitalism appears consistent with – if not an actual cause of – pro-social, tolerant, moral conduct, we might wonder where this leaves its critics. Given the nature of their criticisms, it would be foolish to assume that they do not also value pro-social behaviours, co-operation, trust and prosperity. We are left to conclude, therefore, that they believe either that such things are only realised in spite of capitalist systems (contrary to the evidence presented in this book), or, since capitalism increases overall material prosperity but does not close the wealth gap, that they are not realised to the degree or in the manner desired.

The short concluding chapter discusses the environment and rejects the idea that there is something inherent in capitalism that results in environmental degradation, such that protecting the environment necessitates a shift to some form of socialism. At the same time, the data analysed does not suggest that market solutions alone will do enough to deal with the environmental problems that we face, resulting in Rutar’s recommendation that at this stage, greater regulation is required.

What ultimately emerges from Capitalism for Realists is that, when one considers the available data, capitalism’s critics are often wide of the mark. Indeed, it would appear that in some cases, capitalism is often correlated with (and is perhaps the cause of) the very opposite of the faults of which it is accused. The writing is accessible in the main, though the numerous typographical errors can be distracting and are indicative of poor copy-editing on the part of the publisher. Some of the more detailed statistical discussions can be hard to follow, but this evidence is fundamental to the book’s very project of offering a realistic rather than an ideological assessment. Overall, this is a fairly specialist work which offers a nuanced, balanced, evidence-based analysis of how the modern economy works and what its effects might be.

‘Capitalism for Realists: Virtues and Vices for the Modern Economy’ by Tibor Rutar, was published in 2022 by Routledge (ISBN: 978-1-32-30592-9). 178pp.

Neil Jordan is Senior Editor at the Centre for Enterprise, Markets and Ethics. For more information about Neil please click here.

There are growing concerns that capitalism and democracy are in crisis. Despite the success of free markets in creating global prosperity over two centuries, the recent slowdown in growth in Western economies, the persistence of inflation, increasing economic inequality, financial instability and the explosion in debt have called into question the value of market capitalism. Moreover, trust has been eroded in liberal democracies because of dysfunctional governments, a perceived lack of commitment to truth and political leaders playing the game to the edge of legality. Added to these concerns are the growth of a post-modernist culture with steadily increasing social fragmentation, divisiveness and the lack of a unifying and accepted source of appeal.

We are living in the 21st century in Western societies in which religion has not just been replaced by secularism, but the one God of the Christian religion, with its deep roots in Judaism, has been replaced by the pluralism of the many gods of modernity. As a society we require those in leadership and authority in business and politics to have a moral compass and as Adam Smith set out regarding the virtue of prudence and Burke regarding the role of religion, our fellow citizens need values of honesty and sympathy if we are to seek the common good.

Against this background and under the auspices of the Centre we have decided to launch a series of colloquia in which to explore a Christian perspective on contemporary issues of political economy. On each occasion a small panel of experts will present their thoughts on the chosen topic, and other participants will then have the opportunity to make their own contributions to a free-flowing discussion. Participants will be invited from across the political spectrum and the number kept to around twenty. In the links below you will find the first of these which took place in November 2023 and focused on the theme of ‘Christian Realism’. We hope you find the papers stimulating.

Brian Griffiths (Lord Griffiths of Fforestfach), Senior Research Fellow, Centre for Enterprise, Markets and Ethics.

Ken-Hou Lin is an Associate Professor of Sociology at the University of Texas at Austin and Megan Tobias Neely is a Post-Doctoral Researcher at Stanford University, studying gender, race and social class inequality. They are alarmed by the growth of inequality in the United States of America over the past generation and blame this on the “financialisaton” of the US economy, which they define as “The wide-ranging reversal of the role of finance from a secondary, supportive activity to a principal driver of the economy” (page 10, italics original). They assert that “To understand contemporary finance is to understand contemporary inequality” (page 2) and that previous studies often touch only on fragments of the connection between finance and inequality. Hence, they set out to “provide a more comprehensive synthetic account of how financialisaton has led to greater inequality in the United States” (page 4).

The analysis which follows includes a whistle stop review of the world economic system since the Second World War and a closer examination of many trends over recent decades. Building on the work of others, they bring together copious statistics, particularly in the form of dozens of graphs indicating economic trends. Absorbing the statistics and considering their implications takes time, so this is not a book to be read fast. However it is not a heavy read and does not require a great amount of prior knowledge.

Lin and Neely make a number of interesting observations that deserve careful consideration. These relate to subjects as diverse as the implications of outsourcing, the reluctance of employers to provide on the job training and the risk implications of the modern dislike of investment managers for conglomerates. There is thus much in the book that is worthy of consideration.

Unfortunately, however, the analysis that the authors provide, which purports to bring the wealth of statistical information together, is most unsatisfactory. In particular, the analysis of causation is poor and unpersuasive even in relation to the core thesis of the book. Although Lin and Neely acknowledge the role of globalisation and the growth of IT in increasing inequality (at one point saying that former “is a broadly convincing explanation of rising inequality”, page 38), they dismiss these things as primary factors, regarding them as essentially background circumstances against which other things have resulted in growing inequality. Yet there is no satisfactory analysis to back up this position and their blaming of many US specific factors is somewhat undermined by their frank admission towards the end of the book that “similar trends have unfolded in Europe, Asia, and other countries” (page 181).

The book contains many statements designed to demonstrate that the authors recognise fundamental economic realities and do not wish to deal in caricatures: early in the book, they recognise that finance is indispensable for a prosperous society and dismiss populist claims that financial professionals are evil; they acknowledge that deregulation could be beneficial (citing evidence that suggests that relaxing the US intrastate bank branch restrictions in the 1980s was associated with local economic growth); they draw attention to the problems with Keynesian economics that emerged in the 1960s and 1970s; and they accept the value of many financial products, including derivatives. However, these promising statements are outnumbered by less balanced comments and, at times, careful analysis is replaced by extreme assertions, such as the statement that the profitability of financial ventures “depends on the harm they bring” (page 60, emphasis original) and that finance “has morphed into a snake ruthlessly devouring its own tail” (page 83).

On a number of occasions, the authors come close to Luddism. The statement that the Industrial Revolution “created … massive poverty” (page 29) is extraordinary but irrelevant to the argument of the book. However, other statements are less easily ignored. For example, it is clearly arguable that some of the cost cutting and other actions taken by the management of numerous companies over the past generation has been unduly influenced by short-termism (particularly short-term stock market considerations) and on occasion has been carried out in a way that many would consider reprehensible. If Lin and Neely had confined their comments regarding cost cutting to this then there would have been little to object to in what they say about it. However, they do not: they lump together all cost saving measures and thus fail to recognise the long-term economic benefits of continually increasing efficiency. Thus they comment adversely on those managers who had “a deep conviction that a firm’s performance could be optimised with sophisticated cost-benefit analysis” and that parts of companies should “be evaluated, eliminated, or expanded according to their profitability” (page 87). They also lament the fact that “new technologies have been adopted to replace unionised work forces” (page 110) and the fact that “To maximise returns for shareholders, firms have cut costs by automating and downsizing jobs, moving factories oversees, outsourcing entire production units, and channelling resources into financial ventures” (page 118).

Although in places, the authors acknowledge that things were not perfect in the past and they warn about romanticising it, there is a definite note of nostalgia in the book. On several occasions, they contrast current management attitudes unfavourably with what they perceive to be the objective of US industrialists in past years, namely “to broaden their market share – the prior gold standard for corporate management” (page 180). They also talk fondly of the historic “capital-labor accord” (e.g. page 45) and suggest that there was once “a fair-wage model” that sustained long-term employment relationships (page 47), seemingly blind to the confrontations that dogged industrial relations in the USA and elsewhere through much of the twentieth century. One wonders whether, deep down, they are nostalgic for the days of US economic hegemony and the prosperity that it bought in the generation following the Second World War.

Whatever the deficiencies in the book’s analysis one would have expected it to contain clear policy suggestions but it does not. Lin and Neely urge us to “scrutinise the rules of the game” (page 177) and call for “inventive and carefully considered policies” (page 184) but what follows is little more than a series of vague general comments and micro proposals. It is hard to understand what the authors are advocating. For example, in the introduction, they indicate that they believe that policies targeting high-earners, such as earnings caps and progressive taxes, are necessary but they never explain what kind of earnings caps they have in mind and, in their conclusion, appear to suggest that increasing tax may not be practicable or even the best approach. Likewise, having suggested on various occasions that the repeal of the Glass-Steagall Act (the US Banking Act of 1933) has caused many problems, the authors declare that “The Glass-Steagall era has passed and its restrictions are no longer sensible a century later” (page 184).

The book concludes in an anti-climax: “We suspect that there are many answers to the social question through which economic institutions could be organised and conducted so that all members of society more justly share their benefits. These answers must be imagined” (sic, page 190). Indeed they must, because there is little in the book to tell us what they might be.

“Divested: Inequality in the Age of Finance”, by Ken-Hou Lin and Megan Tobias Neely, was published in 2020 by Oxford University Press (ISBN 978-0-19-0638313). 190pp.

Richard Godden is a Lawyer and has been a Partner with Linklaters for over 25 years during which time he has advised on a wide range of transactions and issues in various parts of the world.

Richard Godden is a Lawyer and has been a Partner with Linklaters for over 25 years during which time he has advised on a wide range of transactions and issues in various parts of the world.

Richard’s experience includes his time as Secretary at the UK Takeover Panel and a secondment to Linklaters’ Hong Kong office. He also served as Global Head of Client Sectors, responsible for Linklaters’ industry sector groups, and was a member of the Global Executive Committee.

Global Discord does not fit neatly into any of the categories of book that are reviewed on this website. It is not primarily a book about business, capitalism or wealth and poverty. In fact, it is not primarily about economics. However, its focus is on something of crucial importance to all of these things: the global political order. Its author, Paul Tucker, the former Deputy Governor of the Bank of England, suggests that “the deep architecture of the international economy [is] influx for the first time in decades” (page 3) and he sets out to analyse both the causes of this and potential responses to it.

He never expressly identifies his intended audience. The primary audience is doubtless those responsible for formulating the policies of Western nations in relation to international affairs, including, in particular, international finance and trade. The issues that he discusses are, however, of crucial importance to a far wider audience. Unfortunately, the book is dense and heavy going in parts. This will limit its appeal but those who take the trouble to study it carefully will find it rewarding, particularly if they seek to reflect on how his suggested approaches to international engagement might be applied in their corner of the global political, financial or business world.

Tucker identifies three major differences between the kind of globalisation that we are now witnessing and that which existed in the past: first, derivative markets have separated cross-border flows of funds from flows of risk; secondly, after accumulating vast sovereign wealth funds, some states have acquired great influence in global capital allocation and, taken with state-owned enterprises, state-capitalist actors are operating on a scale that has not been seen “since Europe’s merchant companies traded and intervened around the planet half a millennium ago” (page 7); and, thirdly, today’s infrastructure for cross-border financial transactions create vulnerabilities that can be weaponised.

Tucker suggests that there is “a deep cleavage in modern international affairs” (page 78) and his overwhelming concern is China. He argues that the West needs to face up to the fact that, far from China moving in the direction of a liberal economic and political order, it is moving in precisely the opposite direction. Quoting the now well-known “Seven No’s” of the Chinese Central Committee, he points out that, “While Western states took different paths to [wielding power across their territories, the Rule of Law, and accountability], for China the destination is different” (page 220). Thus he argues, surely correctly, that “commentators in the West who insist current tensions are not ideological – and should not be allowed to become so – are deeply mistaken, while nevertheless pressing an important practical question: What to do?” (page 461).

He repeatedly accuses Western policy makers of wishful thinking in their dealings with authoritarian states and China in particular and he has many criticisms of current global institutions pointing to both specific design flaws and more general issues. Some of these criticisms relate to specific institutions: he describes the second Basel Capital Accord as “deeply flawed” (page 98) and suggests that the WTO is based on unrealistic universalistic rather than pluralistic concepts. Other criticisms are more general: he points to the hazards of delegation to international organisations, particularly in a world in which international treaties are what economists call “incomplete contracts”, and the dangers of what he refers to as “judicialization”.

His concern in relation to the latter is that international courts and tribunals are ruling on matters that ought to be left to political negotiation and are applying interpretations of treaties and even “natural law” concepts in a way that results in states being bound by things to which they do not believe they ever agreed. Some might argue that this is simply the concept of the Rule of Law applied in an international context but, as is the case in relation to some domestic systems (e.g. the role of the Supreme Court in the USA), it gives rise to a situation that is dangerously close to the Rule of Judges. In short, it is an example of judicial overreach and it has potentially serious political consequences for the perceived legitimacy of the world order, particularly when set against the context of the ideological divide to which Tucker draws attention.

Much of what Tucker says is thus critical of the existing order and those who have contributed to its creation. However, Global Discord is not a negative, destructive book. Tucker’s main aim is to assist in the building of a new global order that is based on coherence defensible principles whilst being capable of surviving in the real world. To this end he devotes a lot of space to analysing the theory of international relations and he suggests that we need to contemplate four broad scenarios for the next quarter to half century: “Lingering Status Quo (continuing US international leadership); Superpower Struggle (the scenario most resembling the long eighteenth century’s French-British contest); New Cold War (autarkic rival blocks); and Reshaped World Order (more Vienna 1815 than Washington 1990)” (page 115).

Against this background, he moves to more specific, concrete issues. The final part of the book includes chapters on the international economic system, the IMF and the international monetary order, the WTO and the system for international trade, preferential trade pacts and bilateral investment treaties and Basel and the international financial system, and the book concludes with an eight page appendix setting out, in numbered pithy points, Tucker’s suggested principles for constitutional democracies participating and delegating in an international system. No-one can accuse Tucker of merely dealing in abstract theory!

Tucker describes his approach as “realist” in the sense that it is “not a morality-first account deriving duties, rights, and legitimation principles from fundamental, externally given, universal principles, with some kind of morality system providing ultimate foundations” (page 268). However, he suggests that his approach does not “consign moral values to the side lines” since it requires “sociability with path-dependent, problem-solving norms, which leaves something to be said about the sources or mechanisms of normativity” (page 268).

Many will criticise this approach. Some will do so on the basis that it is insufficiently “realist”. Many others, especially Christians and others with strong moral compasses, will worry that morality plays an insufficient part in it and Tucker concedes that, in his view, the West has to adopt a “live and let live” policy and accept that engagement with illiberal regimes is necessary despite a possible desire to promote a universal morality-based international order.

Tucker is not a moral philosopher and he does not engage in detail with the moral issues. However, one does not have to accept moral relativism to conclude that there is a good moral case for his overall approach. A purist approach is highly unlikely to have the outcomes desired by its protagonists and could well result in outcomes that cause much suffering, whether by resulting in war or, more likely, by preventing co-operation over issues such as pandemics, mass-migration and climate change and by stifling international co-operation and trade, with the result that prosperity declines and poverty increases. Furthermore, Tucker bases his thesis on some fundamental tenets that are, at heart, moral: the desirability of peaceful co-existence; the idea that “order is not to be sniffed at: war and instability are quite a lot worse, as is fear of them” (page 323); the need to “stake out the ground that constitutional democracies should insist on to avoid sacrificing our deep domestic norms: to remain who we are” (page 356) whilst accepting that illiberal states will remain who they are; and the idea that perfection cannot be demanded, legitimacy is not binary and “Authority can be legitimate if it is the best realistically available” (page 287). Whilst this may not go far enough for some moral purists, there is, at least a strong argument to the effect that Tucker’s overall approach is likely to produce the best realistic outcome for the world political and economic order and is thus fundamentally ethically defensible.

The purists will also have difficulties with some of Tucker’s more specific statements. In particular, his suggestion that “We need to make judgements about the past only insofar as they materially affect the present (through institutions, norms, values, embedded habits, and so on)” (page 316) will not resonate well with those who are urging ever more delving into past wrongdoings. However, the purists have never explained how their approach leads to a world in which people are able to live together harmoniously and productively. Indeed, the proponents of the recent trend in legislation in the UK towards there being no time bar in relation to the raking up of the past should reflect on whether their proposals are as ethically pure as they like to believe. For example, Tucker suggests that “it is simply no good looking back to the Gulag” or various other dreadful episodes of the twentieth century (page 316) but this is precisely what the UK Prevention of Crime Act 2002 requires: it, unrealistically, regards an enterprise that has once been tainted by crime (e.g. those that benefitted from contracts with slave labour in the Gulags or those that assisted the Nazi regime) as forever tainted.

In developing his arguments, Tucker analyses in some detail different philosophical approaches to international affairs and different concepts and models of international co-operation (e.g. the nature of international law). He largely dismisses Thomas Hobbes’s extreme “realism” and criticises John Rawles’s demand for what he regards as an unrealistically “thick” and binary (“in or out”) international order, while acknowledging his debt to David Hume and Bernard Williams.

This analysis of the philosophical underpinning of Tucker’s concepts will enhance the attractiveness of Global Discord for some more academically minded readers. However, it is the primary reason why the book is dense and, in parts, heavy going. Tucker would doubtless argue that the analysis is essential to the development of his case and this is doubtless true. However, on occasions, the reader is left with the feeling that the analysis is a bit laboured and that the language could be simpler. This is a pity because it mars an otherwise excellent and important book that deserves to be widely read.

“Global Discord: values and power in a fractured world order” by Paul Tucker was published in 2022 by Princeton University Press (ISBN-13:9780691229317). 483pp.

Richard Godden is a Lawyer and has been a Partner with Linklaters for over 30 years during which time he has advised on a wide range of transactions and issues in various parts of the world.

Richard Godden is a Lawyer and has been a Partner with Linklaters for over 30 years during which time he has advised on a wide range of transactions and issues in various parts of the world.

Richard’s experience includes his time as Secretary at the UK Takeover Panel and he is currently a member of the Panel. He also served as Global Head of Client Sectors, responsible for Linklaters’ industry sector groups, and was a member of the firm’s Executive Committee.

Global Discord does not fit neatly into any of the categories of book that are reviewed on this website. It is not primarily a book about business, capitalism or wealth and poverty. In fact, it is not primarily about economics. However, its focus is on something of crucial importance to all of these things: the global political order. Its author, Paul Tucker, the former Deputy Governor of the Bank of England, suggests that “the deep architecture of the international economy [is] influx for the first time in decades” (page 3) and he sets out to analyse both the causes of this and potential responses to it.