The parable of the Good Samaritan is one of the most popular, well-known and compelling stories Jesus ever told. Rather than teaching in an academic and rather dry way by making general statements, Jesus taught people by telling stories which caught their imagination. Invariably the stories were simple, direct and human. He recounted this parable in response to the question “Who is my neighbour?” Before looking at the parable in some detail, I owe it to you to tell you why I chose as the title.

Jesus told the story of the Good Samaritan in response to the question ‘Who is my neighbour’? This question was the title of a letter from the House of Bishops of the Anglican Church to the people and parishes of the Church of England in advance of the general election of May 2015. The letter argued that we were losing the concept of neighbourliness in our social life, becoming a ‘society of strangers’ rather than a ‘community of communities’. After the election the Bishop of St. Albans introduced a debate in the House of Lords, in which I took part, in which questions were asked, ourselves, our churches, and the government. As with all such debates there was a response from a government minister, in this case Lord Bridges.

The Bishops of the Catholic Church for England and Wales also released a letter before the election emphasizing the importance of respect for life, marriage and the family and in particular the need to build communities which seek to serve the common good. Both these letters made it clear that our church leaders believed the parable of the Good Samaritan to be relevant today. Not only that, they argued that the parable was a guide not just how we should respond at a personal level to the needs of others, but how we should respond in terms of our life together as a society, and even of social and economic policy. The question I found myself asking was “Was the view of church leaders my own view as a layman of what it meant to be a Good Samaritan?”

A further reason to think about the subject was the Chancellor of the Exchequer’s Summer Budget of 2015. In it he set out to move the United Kingdom from a high welfare, high tax, low wage economy to a low welfare, low tax, high wage, economy. He set out plans to do this through lower taxes for business, the introduction of a compulsory national living wage for all businesses, (considerably higher than the present minimum wage) and cuts in the overall budget on welfare spending through a reduction in tax credits. Moving from a high welfare to a low welfare society is an attempt to change in a significant way the direction of the welfare state.

Within no time Christians who were working with the most needy were campaigning against the policy. Again I was forced to ask myself, ‘What would be the response of the Good Samaritan today to this policy?’

Sign up to receive blogs and book reviews via email

More recently there has been the migration crisis. I chose the title for this address in the early summer, way before the migration crisis hit. There were problems in Calais but what we have seen over the summer – the sheer scale of the numbers seeking asylum and migration, the break-up of the Schengen agreement, and most of all the human suffering conveyed through the images of the abandoned lorry in Austria carrying 71 bodies, the capsized boats in the Mediterranean and the picture on the front page of newspapers of the body of three year old Syrian Aylan Kurdi being carried on a Turkish beach, have forced us to face up to this issue both as individuals and as a nation. I think it’s fair to say that the Prime Minister and the government underestimated the extent to which people in this country had been moved by the scale of this human catastrophe. Once again a question.” If I wished to emulate the Good Samaritan what should I do?”

In the light of these three challenges I have been forced to go back to square one and ask if I wish to follow the teaching of Jesus What does it mean to be a Good Samaritan today?

To start with I needed to look at the parable in greater detail.

The background to this parable was a challenge to Jesus to explain his teaching. Jesus lived in a very religious society and the person who posed the challenge was a lawyer who specialised in understanding and interpreting the Law of Moses. The law was the accepted foundation of social and economic life and the basis of social ethics. In our far more secular society the equivalent I imagine today would be John Humphreys on the Today Programme or Kirsty Walk on Newsnight questioning some moral philosopher or public intellectual about the issue. Believing as he did in an afterlife the lawyer wanted to know how to live his life here and now in this world in order to ensure he attained life in a future world, or to use the words of the King James version, “What must I do to attain eternal life?” Jesus responded to his question with a further question, ‘Tell me what the Law itself says?’ The lawyer replied with two quotations: both from the Torah.

First, ‘Love the Lord your God with all your passion and with all your being and with all your strength and with all your intelligence” (Deut. 6:5), and second, ‘Love your neighbour as yourself’ (Lev.19:18)

Quick to embarrass Jesus the lawyer shot a further question at him ‘And who is my neighbour?’ Being a neighbour meant belonging to one’s tribe, one’s race, one’s people. Being a Judean or Galilean was very different from being a Samaritan or a Gentile. Accepting that someone was a neighbour implied a responsibility to look after them. They were members of the same community and to help them was to show solidarity with all others in the group.

Jesus responded to this loaded question by recounting the parable.

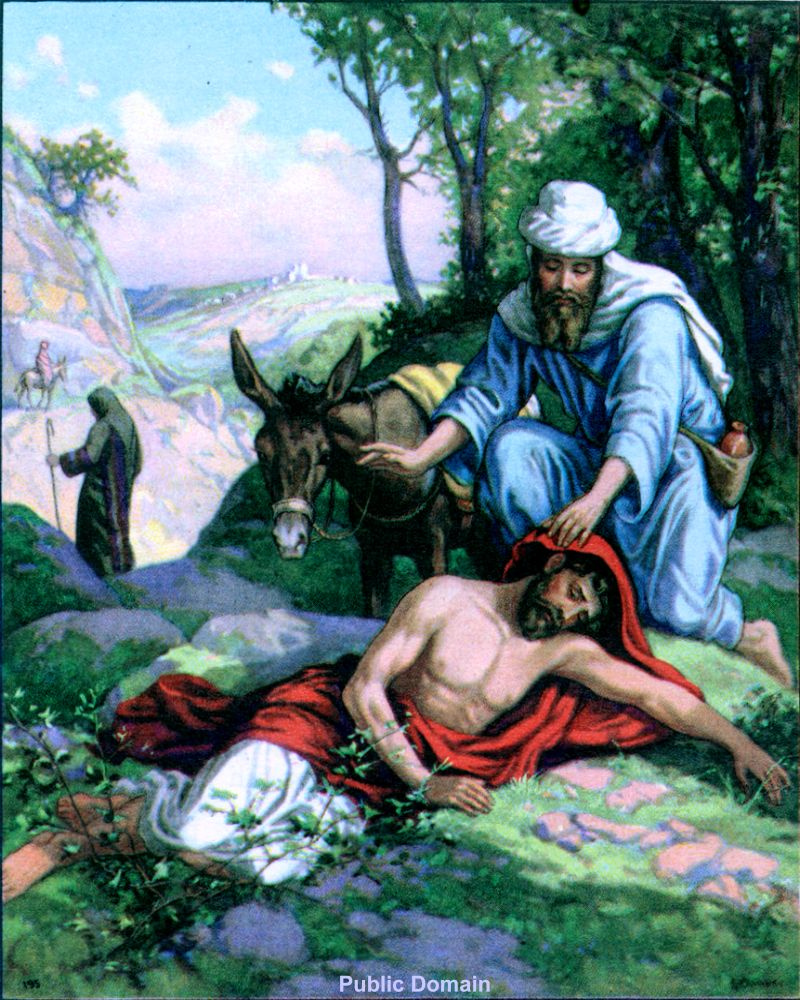

A man was travelling from Jerusalem down to Jericho and was attacked by a gang of thieves. They took his clothes, beat him and left him naked, apparently looking as if he were half-dead. By chance a priest was travelling down the same road. He saw him but deliberately walked on the other side. Later a Levite, one of the staff employed at the Temple in Jerusalem was also traveling down the same road. He also saw him but again he passed by on the other side of the road. Finally a Samaritan, a foreigner, and by upbringing and culture a heretic and sworn enemy of the Jewish people saw him. The text says he had compassion for him, administered first aid by disinfecting and bandaging his wounds, lifted him onto his animal and led him to an inn. The following day he gave the inn keeper two silver coins with the request, ‘take good care of him and if it costs more, put it on my bill – I’ll pay you on my return journey’.

Which of the three Jesus asked the lawyer was neighbour to the victim. Embarrassed to identify him as a Samaritan, the lawyer replied, “the one who treated him kindly”, to which Jesus added ‘go and do the same’.

This parable was a realistic story. The road from Jerusalem to Jericho is certainly downhill as I know from personal experience travelling on it the week before last. Jerusalem is 2550 feet above sea level. Jericho is over 800 feet below sea level, the lowest point on earth and the distance between the two is roughly 17 miles.

Today the road is a dual carriageway. Then it would have been an unmetalled dirt track. The landscape is still rocky and barren and in the summer with no rain and no green vegetation, the scenery is an unending and intimidating ochre as far as the eye can see. If you turn off the main road, you are immediately on minor tracks, which because of their unexpected twists and turns through sharp valleys expose the dangerous nature of such any first century journey. A Hollywood studio could not have constructed a more menacing set in which to show the danger of such a journey. Incidents such as this involving muggings and robberies were common on the road at the time. Even after Jesus time it continued to be dangerous to travel in this area, which is why half-way down on the right hand side of the road, the Crusaders in the eleventh century built a fort on top of the ancient Byzantine fort of Maledomni in order to protect pilgrims travelling along the route.

The victim in the story was most probably an Israelite. The priest and Levite might not have been bad people. If they stopped to help him they might have felt that their own lives might have been in danger. They might also have felt there was little they could do. As professional religious people they may have had qualms about defiling themselves with what could be a dead person. All these are matters for our imagination. The one thing however which is not left to our imagination is that both the priest and the Levite passed by on the other side. Indeed the expression to pass by on the other side, has become an idiom in our language.

We all aspire in one way or another to be a Good Samaritan. What lessons does it have for us?

I believe first this story is a great personal challenge to each one of us. What was different about the Samaritans response? To start with he went out of his way to discover for himself the man’s circumstances. The text says “he went to him” to find out at first hand the man’s condition. His response was more than empathy. He didn’t just identify with the victim mentally. The nature of his response is not conveyed adequately by words such as “he took pity”, “he was moved”, “he had compassion”. The Greek verb which is used suggests something much stronger. It was as if he had been struck by a bolt of lightning which had left him completely shaken. His response was visceral not cerebral. He was so moved he felt compelled to act. He committed himself regardless of the danger he himself might face. The evidence of his commitment is what he did. He gave his money and he gave his time.

The point of the parable is that it turns the lawyers question on its head. The Samaritan did not ask “who is my neighbour?” hoping to be able to divide the world into neighbours and non-neighbours. He found himself asking a more searching question, “to whom am I a neighbour?” For the lawyer the term Good Samaritan would have been an oxymoron, a contradiction in terms. For him to discover that the wounded man, most probably an Israelite, had been helped by a racial enemy, someone from outside the community, was not just a surprise but a scandal. Imagine you were walking at dusk in a dangerous part of London. You are attacked, beaten up and seriously injured. People ignore you because they are frightened. A young man stops to help you. Takes of his coat, puts it under your head, calls an ambulance. When you’re recovering in hospital you discover he is a Syrian refugee and by faith a Muslim.

When we pose the question ‘who is my neighbour?’ are we not also seeking the timeless quest for a loophole to divide the world into neighbours and non-neighbours: the deserving poor, the undeserving poor; the refugee, the economic migrant; the freedom fighter, the terrorist; the needy, the scrounger; the shirker, the worker. The lawyer was searching for a clear definition which would set a precise boundary between those who deserved help and those who did not.

Prof. T.W.Manson, who was a distinguished biblical scholar of the last century suggests that the question asked by the lawyer, “who is my neighbour?” is unanswerable. “The point of the parable is that if a man has love in his heart it will tell him who his neighbour is: and this is the only possible answer to the lawyer’s question”. (T.W.Manson, the Sayings of Jesus, P.308) You don’t have to be a Christian to have love in your heart, but without love in your heart it’s a presumption to call yourself a Christian.

The Good Samaritan not only showed compassion. He provided practical help meant action and the provision of resources.

The late John Stott relates the story of a country vicar to whom a homeless woman turned for help and who promised to pray for her doubtless sincerely and because he was busy and felt helpless. She later wrote this poem and handed it to the regional officer of the housing and homelessness charity, Shelter.

“I was hungry,

and you formed a Humanities group to discuss my hunger.

I was imprisoned,

And you crept off quietly to your chapel and prayed for my release.

I was naked,

And in your mind you debated the morality of my appearance.

I was sick,

And you knelt and thanked God for your health.

I was homeless,

And you preached to me of the spiritual shelter of the love of God.

I was lonely,

And you left me alone to pray for me

You seem so holy, so close to God

But I am still very hungry – and lonely – and cold.”

The Good Samaritan had compassion. He offered practical help. He also took responsibility to see that the victim was restored to health. The help he gave was not just to bandage the wounds. It was not just short term help. It involved accepting responsibility that the person was provided with the care and the resources to put him on his feet again.

Sometimes in churches and charities we welcome a person whose needs we only partially know. We create high expectations for them of the nature of the community of which they are now part. After a time we realise that their problems are long term and more intractable. As people they are far more demanding than we originally thought. In the end we too decide that we are too busy and so, almost imperceptibly we move to the other side of the road and move on, sometimes with tragic consequences.

The story of the Good Samaritan has not only inspired individuals. It has inspired churches, charities and governments to care for those in need. In the nineteenth century endless charities were set up to ease the brutality of industrialisation. Christians supported the establishment of trade unions and voluntary organisations which provided support for those unemployed through sickness, injury or market forces. Earlier in the century government reforms led to the abolition of slavery and the outlawing of children as chimney sweeps.

The first labour exchange was set up in the Upper Thames Street in London in 1980 by the Salvation Army. The term the welfare state was first coined by the Archbishop of Canterbury, William Temple in the early 1940’s. His book Christianity and the Social Order argued a powerful case for a welfare state of the kind set up by the Attlee Government after 1945. It was a case which found substantial public support.

Times change and today many people would not associate the modern welfare state with the parable of the Good Samaritan. There is considerable public scepticism of the welfare state. The television programme Benefits Street created a stir by its exposure of the scale of benefit dependency and the right to benefit entitlement which people expressed. The latest issue of the official government publication, British Attitudes Survey (2015) reported that public support for welfare spending in this country has been in long term decline. Support for the statement that “government should be spending more on welfare benefits for the poor” fell from 61% in 1989 to 30% in 2014. The public perception is that welfare has become too centralised, too disjointed and too impersonal.

How therefore should we think about this issue?

In the first place the hallmark of a Christian response to the suffering of fellow human beings must start with compassion. For me the most significant aspect of the parable of the Good Samaritan is that when he saw the condition of the victim ‘he had compassion’. Compassion must be the basis of any response we make as Christians to human suffering and in whichever way we chose to make it – personal, social, governmental.

Next it is important that we take the whole of Christian teaching into account and not select certain parables and texts. In addressing a large crowd of people (Lk 14:25-33) Jesus spelt out the cost of following him and used two parables to explain the importance of prudence. A person wishing to build a tower will first sit down, estimate the cost and figure out if he has the resources to proceed. Similarly he told the story of a king who was eager to wage war on an enemy but who must first consider whether with ten thousand soldiers he is able to withstand an army of twenty thousand men. Compassion may suggest an immediate and dramatic course of action but prudence is a necessary check to avoid a response which is unsustainable in the longer run.

In terms of the welfare budget prudence suggests that at the very least it must be sustainable and have public support. It must address the roots of poverty so that children brought up in poverty today do not become parents living in poverty tomorrow. To address this the Early Years from pregnancy to the first day of school are crucial. This is a people to people issue, not just a money transfer. It must tackle the growth in the dependency culture and offer better ways of returning to work. Unemployed people need personal help. For young people known as NEETS – not in education, employment or training – once again a cash handout is not enough. It’s through personal help and support that they realise their potential.

If the parable of the Good Samaritan has one main message for us today it is that people in need certainly require resources to help them. But money of itself will never be enough. They require personal help, personal encouragement, personal friendship and dare I say it, love.

In terms of migration the leadership of the Church of England is of the view that we could take more than double 20,000 refugees over a five year period which the Prime Minister has recommended. Parishes could do more to welcome those who are fleeing from war and persecution. One initiative, the Welcome Box based in Derby, which provides a box of gifts and information delivered by a church volunteer to help people newly housed in the area integrate into the community. The migration crisis is a tragedy: for the church it is a huge opportunity.

At the same time a functional state needs to define its borders, defend them and maintain law and order within them. Without this a state becomes dysfunctional. This is not the occasion to discuss the complex political issues Europe faces in response to the scale of the crisis, simply to recognise that dealing with it involved massive challenges such as ending civil wars and persecution in those countries from which refugees flee, building viable economies in those same countries and,. making sure detention centres can process more rapidly claims for asylum.

What is not acceptable in my view is for European countries to give conflicting signals: to say one day that migrants are welcomed but then to announce that after a stay of month’s or even years they may be deported.

In the parable the Good Samaritan showed compassion. He also showed prudence in that he promised the inn keeper funds to help the victim get back on his feet again.

Who then is the Good Samaritan today? A person of compassion, who takes ownership of the situation, offers practical help, concerned with restoration as well as rescue, long term not short term, offers time and money, however small, and is blind to race, colour, creed, gender, status, income and life style. What is important is that we as communities and as a society must be concerned within the long term flourishing of individuals and families and not just with offering short term financial help. Governments in particular have a crucial role to play in addressing the underlying causes of migration, which is easily said but hugely complex to accomplish.

The parable has a personal application for us all. It also has implications for churches, charities and governments. There is however a third dimension to the parable to which I would like to draw your attention.

I was brought up in a Christian tradition which had little regard for the church fathers, men such as Irenaeus, Clement of Alexandria, Origen, John Crysostom, Ambrose, Augustine. The church Fathers understood the parables not just as stories but as allegories. They were interested to discover their hidden meaning, what it told them about Jesus and his Kingdom – the Kingdom of God – which he had come to establish. There was precedent for doing this in the way for example that Jesus interpreted the parable of the sower, when asked about its meaning by the disciples (Mk 4:1-20). The individual details of their allegorical interpretation vary from one church father to another. Because some are excessively rich in the use of imagination they are easily parodied and ridiculed. However the parables invariably relate to the mission of Jesus and are there to help us have faith in Him and the Kingdom he came to establish. Pope Benedict XVI has referred to the allegorical meaning of parables as their “inner potentiality”, which I like.

For the Church Fathers the road from Jerusalem down to Jericho was a picture of human history. The victim is an image of ‘Adam’, of mankind in general, Everyman, who has been ‘robbed of immortality’ (St.Augustine). The half-dead man lying on the roadside is a symbol of the universal experience of human history in which mankind has been wounded through alienation, oppression and suffering. St Bede said that “sins are called wounds because they destroy the integrity of human nature” (Bede). The Good Samaritan is an image of Jesus Christ himself. By becoming like one of us he has shown us the true meaning of compassion. “This is how God showed his love among us: He sent his one and only son into the world that we might live through him” (Jn 4:9). The oil and wine poured into his wounds are the healing gift of the sacraments. The inn to which he was brought is the church which cares for us.

I believe the church Fathers were right when they recognised that we are all alienated and wounded like the victim. We all need healing to become fully the neighbours we can be. We experience that healing through responding to the love of God which is found in Jesus who loved us enough to become a neighbour to us, so that we can become neighbours to others.

This is a transcribed speech given at the Chilterns Prayer Breakfast on October 9th 2015.

Lord Griffiths is the Chairman of CEME. For more information please click here.