The company American Rounds is supplying vending machines from which gun owners can buy bullets, with machines currently available in food shops in the states of Alabama, Oklahoma and Texas. There are plans to expand this provision to states where hunting is popular, such as Louisiana and Colorado. Customers simply select the ammunition that they would like to buy using a touchscreen, scan their identification and collect their bullets below, the machine having used ‘built-in AI technology, card scanning capability and facial recognition software’ to match the buyer’s face to his or her ID and to ensure that he or she is over 18 years old.

The states in which such machines are available at present place no minimum age limit on the purchase of ammunition, do not require the vendor to keep a record of the purchaser, impose no licensing regime for the sale or purchase of ammunition and do not prohibit those disqualified from purchasing or owning firearms from buying ammunition (though federal laws might impose such a restriction, without necessarily obliging vendors to check whether a customer is in fact disqualified). It would therefore seem that in checking the ID of a purchaser and maintaining a record of the transaction, the machines provided by American Rounds arguably do more than state law requires. This might be for the purposes of ensuring that the machines are unquestionably within the law, or, by ensuring sales are made to adults only, it might be an exercise in reputation management – perhaps both – but it does mean that the machines are likely to be legally compliant when installed in other states where tighter restrictions may apply.

Artificial Intelligence, Risk and Trust

Without entering into the wider issue of gun ownership and its regulation, there are nonetheless moral questions regarding the provision of something so potentially dangerous by way of a vending machine. Can we be certain that the technology will always perform as it is supposed to? We might ask whether such machines capable of discerning a forged ID from a genuine one. Moreover, will they identify buyers correctly? After all, numerous cases (at least seven in the US last year) have been documented of wrongful arrest as a result of facial recognition technology and it would appear that some technologies of this kind are prone to reflecting and perpetuating biases in the data with which they are trained. Whether the technology in American Rounds’ vending machines will accurately match the purchaser’s face to a photograph on an identity document is therefore a legitimate question. These concerns raise the much broader question of responsibility.

Decisions, Decisions…

Where there exists a right to own firearms and ammunition, there is no prima facie reason to disallow sales of ammunition provided by technological means, provided that the technology is reliable and ensures that sales are only ever made to the right people. What, then, is the role of people in such transactions? In a jurisdiction in which would-be buyers of ammunition were checked against a register of individuals disqualified from buying or owning guns, one would expect purchases to be carefully monitored – not least because the shop-owner’s livelihood is likely to be at risk for breaches of regulations. Such verification would doubtless be conducted by means of access to a database, such that the checks, while instigated and concluded by a human-being who makes a decision ‘in store’, would nonetheless be dependent on technology. Ultimately, therefore, while relying on the information provided, the individual vendor would be responsible for the sale. The question, then, is whether this decision, based on the same information, might safely be deferred to a machine that uses facial recognition software and searches databases itself.

The risks involved are different, but a similar question can be asked about the sale of alcohol. Practices vary but in some countries, alcoholic drinks can be bought from vending machines, with the identification of the buyer being verified either by biometric data gained by scanning the customer’s fingerprint, or by simply supplying the purchaser with a wristband to show that his or her ID has been checked by a member of staff. In other countries, alcohol can only be bought at certain times from state approved vendors.

Decisions and Responsibility

Whether the sale is of alcohol or ammunition, are those businesses and states who continue to require and rely upon a human decision at some stage in the transaction doing so based on an unjustified our outdated mistrust of technology, or because they acknowledge that responsibility can ultimately only be attributed to free human beings, who recognise the potential consequences of error? The question, therefore, becomes one not only of trust, but also of responsibility in relation to technology. Where certain decisions handed over to technology – which, of course, can be done more easily and more safely in some areas than in others – we are left with the matter of where responsibility lies, particularly when the technology ‘gets it wrong’. Other things being equal, the owner of a hunting supplies store will be liable if he or she sells a firearm to someone who is underage or disqualified from purchasing guns. Where does responsibility lie if a vending machine sells alcoholic drinks to children in error? Does this rest with the corporate owners or suppliers of the machine? If the machine is on licensed premises, is the landlord responsible? Perhaps there is a case for holding the suppliers of the technology used by the machine liable. This might not be a straightforward matter, as fatalities involving self-driving cars demonstrate: in one case, the back-up driver of the vehicle was convicted while the operating company was judged not to be criminally liable. When an algorithm becomes involved in decisions relating to sentencing for criminal misdemeanours or the provision of social security, where does responsibility for those decisions lie?

Regardless of the scenario, responsibility, as a moral category, must always reside with a person or (human) organisation, never a machine. Machines, however ‘intelligent’, are neither conscious nor free and as such, they are not moral agents. Where decisions are devolved to technology – and that technology ‘decides’ incorrectly – the challenge is for us to identify the responsible subject.

Neil Jordan is Senior Editor at the Centre for Enterprise, Markets and Ethics. For more information about Neil please click here.

This paper is part of a series of essays that seek to explore the current and prospective impact of AI on business. A PDF version can be accessed here.

The advent of Artificial Intelligence (AI) upon the business world raises a myriad of challenges and opportunities for management theorists. The first of these is a matter of considered choice: Which are the most suitable theoretical lenses that one might apply in understanding the novel phenomena that AI represents? Might one start with Taylorism and the scientific management approach, or perhaps rather turn to Henri Fayol and his pioneering work on administrative management theory? Still, it may be wise to go back and consider Weber’s work on hierarchy and the resulting Bureaucracy Theory, or perhaps Elton Mayo’s advancements in Human Relations Theory and the creation of ‘humanistic organisations’.[1] Modern managerial thought (post-WW2) brought us the pioneering work of Joan Woodward and Contingency Theory which cannot be ignored. In the realm of psychology and the broader expansion of behavioural science and personnel management, we have Maslow’s influential Hierarchy of Needs and Douglas McGregor’s Theory X and Theory Y. Far from being exhaustive, this list illustrates the plethora of avenues that are available to the inquisitive researcher. This paper, however, elects what many might consider a less obvious choice – that is, an analysis of AI through Peter Drucker’s writings and more specifically, through his concept of the ‘Knowledge Worker’.

It is important to note from the onset that when referring to AI here we are referring specifically to Generative AI, which represents a branch of the wider field that is artificial intelligence, the main distinction being that generative AI has the capacity to learn and produce novel output autonomously.

In an article in the California Management Review during the winter of 1999, Drucker made a compelling statement:

The most important, and indeed the truly unique, contribution of management in the 20th century was the fifty-fold increase in the productivity of the manual worker in manufacturing. The most important contribution management needs to make in the 21st century is similarly to increase the productivity of knowledge work and knowledge workers. The most valuable assets of a 20th-century company was its production equipment. The most valuable asset of a 21st-century institution (whether business or non-business) will be its knowledge workers and their productivity.[2]

Throughout his lifetime Peter Drucker proved to be a prolific writer, having published some 41 books and countless articles, essays and lectures. The totality of his work amounts to over ten million words which as one scholar put it, is the equivalent of 12 Bibles or 11 Complete Works of Shakespeare.[3] No wonder then, that his alias as the ‘Father of Modern Management’ is a fitting title.

Drucker was born in Vienna in 1909 into a Lutheran protestant family.[4] His father was a lawyer and civil servant, and his mother studied medicine – both parents were considered intellectuals at the time. His house often served as a place of congregation for scientists, academics, and government officials, who would meet and discuss new ideas.[5] Yet his formative years were spent at Hamburg University, where he read international law and became heavily influenced by the works of Kierkegaard, Dostoevsky, Aquinas, Luther, Calvin and Weber. Here he developed a sense of Christian responsibility In tackling life’s challenges and made it his life mission to discover a society‘…in which its citizens could live in freedom and with a purpose’.[6] Interestingly, he was not swayed by Marxism because, in his view, the will of the collective came at the expense of the freedom and purpose of the individual: ‘there was no capacity for individual purpose in a collective society’, Drucker remarked.[7]

Amongst scholars and business executives he is perhaps best known for his work on decentralisation and a management approach that emphasises the value of employees and their contributions in achieving the shared goals of the organisation. His most celebrated theory is Management by Objectives (MBO Theory), initially presented in his 1954 book, The Practice of Management,[8] which was later refined in his 1974 magnum opus, Management: Tasks, Responsibilities, Practices.[9] Yet, Peter Drucker’s most distinguished and lasting contribution came in bringing about a novel way of understanding the field of management as an integrative whole. Previous writers such as Rathenau, Fayol, and Urwick drew connections between the varied functions of management, but it took Drucker to tie in all the strings and establish Management as a standalone discipline of study and practice.[10]

Drucker also fundamentally changed how employees were to be viewed by the company. He was the first to argue that they represent assets, not liabilities, and that within the modern economy, employee value and development is crucial to the well-being of the organisation.[11] Indeed, it is in the company’s best interest to invest and support career learning and the continual growth of its employees.

The Effectiveness of Knowledge Workers

Drucker first introduced the concept of a ‘knowledge worker’ in his 1967 book, The Effective Executive, where he defined it as ‘…the man who puts to work what he has between his ears rather than the brawn of his muscles or the skill of his hands’.[12]

He understood and foresaw the seismic shift that the well-developed economies of the West would experience in transitioning from a largely manual workforce to a predominantly knowledge-driven economy. The kickstart to all of this was, of course, the revolution in Information Technology (IT) from the 1950s onwards. Drucker explains that: ‘Today, however, the large knowledge organisation is the central reality. Modern society is a society of large organised institutions. In every one of them, including the armed forces, the centre of gravity has shifted to the knowledge worker’.[13]

What, then, makes the knowledge worker valuable? It is, put rather crudely, his or her ability to make a contribution to the firm. Unlike manual workers of the past, the knowledge worker benefits from a degree of heightened indispensability since the driving source of their effectiveness lies not in machinery or even in skill, but in the knowledge and judgement found between their ears. The concept of effectiveness becomes a key theme in Drucker’s writing on the knowledge worker: ‘…[those] schooled to use knowledge, theory and concept rather than physical force or manual skill work in an organisation and are effective only in so far as they can make a contribution to the organisation’.[14]

This raises questions surrounding the measurability of effectiveness of knowledge workers. It is important and interesting to note that throughout the 1950s the term ‘productivity’ was not yet in widespread use, hence Drucker’s reliance on ‘effectiveness’ as an early substitute. The traditional methods of measurement applied to manual work would no longer apply to knowledge work. The ‘yardsticks’ used for manual work such as industrial quality control or total output generation are ill-fitted to the knowledge worker. The knowledge worker also cannot be monitored ‘closely or in detail’, such an effort is futile for the organisation.[15] Instead, all efforts must be concentrated on the effectiveness of the knowledge worker. Drucker here usefully points out that unlike the manual worker, the knowledge worker produces immaterial things: knowledge, ideas, and concepts that remain unquantifiable in a physical sense. Instead, the ultimate task of the knowledge worker is to convert these abstract intangibles into tangible effectiveness for the organisation, this being in stark contrast to the manual worker who needn’t have to undergo this step of conversion – their contribution being already justified by the goods produced. Therefore, ‘Knowledge work is not defined by quantity. Neither is knowledge work defined by its costs. Knowledge work is defined by results’.[16]

If the knowledge worker ‘thinks’ in his or her contribution to the firm and this ‘thinking’ yields favourable results for the organisation, then surely the principal aim of the knowledge worker is to develop and grow their thought processes. In this sense they are all executives because they possess the capacity as well as the permission (given by their superiors or the company in general), to enact impactful decisions that are a direct result of their thinking.[17] Surely, then, the following challenge is one of discernment in differentiating the right decisions amidst the wrong ones. Within such a context, how might knowledge worker effectiveness be gained?

Drucker argues that it has nothing to do with personality traits: ‘Among effective executives I have known and worked with, there are extroverts and aloof, [others] even morbidly shy. Some are eccentrics, others painfully correct conformists. Some are worriers, some are relaxed. […] Some are men of great charm and warmth, some have no more personality than a frozen mackerel’.[18]

If personality traits have little to no bearing on effectiveness, or at least there is no evidence to prove the contrary, what does have an impact on effectiveness? Drucker argues that effectiveness ‘…is a habit, that is a complex of processes’. There is no silver bullet when it comes to seeking knowledge worker effectiveness, rather, it represents a collection of practices and habits that collectively amount to favourable results for the employee as well as the organization. The beauty of it is that practices and habits can be learned, meaning that any knowledge worker has the capacity to become effective.

However, as Drucker points out, ‘practices are simple, deceptively so; […] practices are always exceedingly hard to do well’.[19] There are five key practice areas that executives and knowledge workers need to master should they wish to become ‘effective’. The first is time – an effective knowledge worker knows what their time is mostly spent on and controls the allocated time that they have at work. The second is a focus on outward contribution – keeping one’s ‘eye on the ball’ so to speak. The effective knowledge worker always maintains an awareness of the overarching goal which helps direct the smaller practices and offers mental guideposts in achieving the desired outcomes. The third area is a sober awareness of one’s strengths and weaknesses. Effective workers build upon their strengths – be those inherent, personal strengths or the strengths conferred on them by their position within the organisation. The fourth area is the ability to distinguish what approaches are likely to yield the most impactful results and focus primarily on them. The fifth and final area is a fundamental understanding of the decision-making process and how to navigate it to make effective decisions. They are aware of operating within a system where too many, sometimes hasty, decisions, can lead to poor outcomes. Only a carefully thought-through strategy will result in favourable outcomes in the long-run.[20]

Drucker and Technology: The Impact of AI Upon the Knowledge Worker

What would the likely impact of AI be on the knowledge worker within such a context? The aforementioned five areas of practice offer multiple viewpoints for one to postulate how AI might augment (or replace), the daily activities of the knowledge worker.

When it comes to matters of automation and the arrival of new technologies, Peter Drucker warns against a position of extremes: technology is seldom a total panacea or an absolute disaster.[21] Indeed, in 1973 he pointed out that, ‘The technology impacts which the experts predict almost never occur’.[22] Drucker would have experienced the early hype surrounding digitalisation and the purported gifts of computing in the 50s and 60s. In some of his earlier writings he branded the computer a ‘mechanical moron’ – one that is very able at storing and processing precise data yet omits all that represents unquantifiable data, the problem of course being that it is often exactly this ‘unquantifiable data’ that becomes essential to the success of the organisation in the long-run.[23] It is often not the trends themselves that dictate a company’s future but rather changes in trends and the unique events which, at least in the early stages, are yet to be quantifiable. They are too nascent to become ‘facts’ and by the time they do become facts it is often too late. Drucker points out that the logical ability of computers represents both their biggest strength and their biggest weakness. One advantage that humans hold over the machine is their enhanced sense of perception and intuition. However, there is a serious risk that executives (i.e. all knowledge workers), might lose this sense of perception if they rely too heavily on quantifiable, computable data at the expense of unquantifiable, qualitative data.[24] This is a behavioural challenge that needs emphasising.

AI: Data versus Information

The resulting key theme that emerges in Drucker’s writing is the notion of data versus information. It’s relevance to analysing the potential consequences of AI lie within the wider scope of using software to effectively manage data. The crux of the problem is as follows: data, in its raw form, is inconsequential until it is interpreted and acted upon. Too many knowledge workers are ‘computer literate’ but not ‘information literate’: they know how to access data but aren’t adept at using it.[25]

For over half a century, Drucker argues, there has been an overwhelming focus on the ‘T’ in IT and the development of technology that stores, processes, transmits and receives data, but not enough effort has been placed on the ‘I’: What does this data mean to me? What does it mean to my business? What purpose does it serve? These are all fundamental questions that haven’t been given the prominence they deserve. [26] The main challenge is to ‘…convert data into usable information that is actually being used’.[27] This has ultimately resulted in decades of computer technology serving as a producer of data and not a producer of information. Drucker, quite rightly, points out that computer generated information has had practically no impact on a business deciding whether or not to build a new office, or a county council deciding to build a new hospital, a prison, a school and so on.[28] The computer has had minimal impact on high-level decisions in business.

Yet this is not just a failure of technology or even of some form of stubbornness amongst knowledge workers and executives; it is principally a failure of providing relevant information that is needed to perform and/or change the direction of any given task.[29] This effort is personalised and applies to each individual worker or executive. The focus then shifts from data gathering to data interpretation but, as mentioned, also to an astute discernment in organising and acting upon said data. The availability of data becomes second to the usability of data. Efforts move toward organising, interpreting, and acting upon reliable data.

As information is the principal resource of knowledge workers, Drucker suggests three broad organisational methodologies. We will briefly detail each in part and thereafter consider the potential implications of AI.

The first is called Key Event which looks at one or multiple important events that have a major contributing role towards the end performance of the knowledge worker. [30] This can be a single event or, as it is often the case, a series of key events that may direct certain outcomes. The event(s) in this case act as a ‘hinge’ upon which performance is dependent. Any executive or knowledge worker stands to benefit substantially in his or her career if they are able to identify, interpret and act upon such events.

The second methodological concept is based on modern Probability Theory and its resulting Total Quality Management (TQM).[31] This approach looks at a variety of possible outcomes that are expected to fit within a given range (i.e. withing the normal probability distribution), and singles out the outliers (those that do not meet the criteria). These exceptional events automatically move from being data (where no action is needed), to being information which necessitates immediate action.[32] This approach is useful when overseeing something like a large manufacturing process but can also be applied to the provision of services, for instance, a client going bankrupt, a deal falling through, a project yielding unexpectedly poor results, etc.

The third methodology for organising information is similar to the second and is based upon the Threshold Phenomenon and the field of perception psychology pioneered by the German physicist Gustav Fechner (1801-1887).[33] This holds that humans only perceive events to become a phenomenon once they cross a certain ‘threshold’ – and the threshold itself is subjective to each individual. In physical pain we only experience it once the stimuli are of such an intensity that they become categorised as ‘pain’. Similarly, it is the intensity and/or frequency of certain data points that lead to their recognition as phenomena. Drucker argues that accurately identifying the phenomena can assist knowledge workers (or managers, executives) in the early prediction of trends. The threshold concept is highly useful in identifying which sequences of events are likely to become trends and require immediate attention.

Conclusions: striving toward AI as a generator of useful information

How might AI assist within this context? The methodologies of organising data are effectively attempts to filter out and sieve the critical information from what otherwise is a plethora of largely useless noise. AI has a major role to play not merely in data monitoring and gathering but increasingly in extraction and accurate interpretation. Here lies the biggest challenge: which AI Large Language Model (LLM) will emerge as the most capable and useful to the knowledge executive?

The reality is that there are likely to be several dominant LLMs with differing traits and characteristics. It is becoming increasingly clear that a multimodal system will benefit from the advantage of being able to receive and work across differing types of data, including text, images, sound, and video. However, multimodality alone won’t suffice if the AI performs poorly at data interpretation and reasoning (e.g. hallucinations, general black box optimisation issues, and so on). We are currently in the nascent stages of a more in-depth, multi-layered reasoning approach with companies such as Meta and OpenAI investing heavily in the ability of AI chatbots to reason memorise, and comprehend more complex challenges. OpenAI’s chief operating officer Brad Lightcap said that in the near future, ‘We’re going to start to see AI that can take on more complex tasks in a more sophisticated way. […] I think we’re just starting to scratch the surface on the ability that these models have to reason. [Today’s AI systems] are really good at one-off small tasks, [but they are still] pretty narrow in their capabilities’.[34]

Again, for AI to have a significant impact on the decisions of knowledge workers they need to possess the capacity to provide a consistent supply of relevant, actionable information. We can already see the underpinnings of a technological infrastructure that may facilitate this: continued growth in the Internet of Things (IoT), the proliferation of AI hardware and artificial neural engines in a rising number of products and services, the consolidation of reliable datasets used to train LLMs, the fine-tuning of AI chatbots with specific characteristics and so on. This also creates a pool of moral and ethical challenges for executives: issues around data privacy, misinformation, bias, fraud, manipulation (e.g. impersonating people to promote products or services via ‘Deepfakes’), the recurring problem of AI hallucinations and so on. All of these issues require careful consideration. However, at this stage the importance of AI’s primary function as a provider of useful information cannot be understated. It may well represent the pivotal element in determining the success or failure of generative AI within business and beyond.

Andrei E. Rogobete is Associate Director at the Centre for Enterprise, Markets & Ethics. For more information about Andrei please click here.

This blog has also been published by the Catholic Social Thought website at St Mary’s University, where there are also many other useful resources on Christian social thought.

Despite the strong interest in property rights in Catholic social thought and teaching, their importance is rarely linked to the topic of the preservation of the natural environment. There is a clear prima facie case for doing so. It starts with what is often described as the ‘tragedy of the commons’.

Imagine, we have a forest, and nobody owns the forest: that is, it is a ‘common’. What will happen? People will come and harvest the trees for firewood, for sale or for industrial use, and they will not replace them. They will take as much as they can without restraint because, if one person or corporation does not harvest the timber, another will. And will anybody plant trees to replace the ones harvested? Of course not. If anybody plants trees, there is no chance they will be there in 20 years’ time for the person to harvest. We cannot expect all people to behave altruistically all the time and certainly should not organise our institutions assuming that they will do so.

If we do not have some way of controlling use, ascribing ownership and usage rights, and enforcing those rights, environmental resources will be exhausted.

If we have a private owner of the forest resources, that private owner will get the benefit of harvesting the trees in the indefinite future. The owner will want to make sure that there is sufficient replanting done to ensure that the forest is self-sustaining. The trees are a valuable resource. But the land is even more valuable if it carries on growing trees for harvesting year after year.

Sign up for our Substack to receive new blogs directly in your inbox!

This does not just apply to private ownership: government or community ownership might work in some circumstances. Indeed, it might be necessary at times, though it would be highly inefficient if the government owned all our environmental resources.

At the same time, property rights have to be enforced. The World Wildlife Fund, for example, estimates that, in Peru, illegal logging is 80 per cent of total logging; it is 85 per cent of total logging in Myanmar; and nearly 65 per cent of total logging in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Illegal logging is the lead cause of degradation of the world’s forests.

We need both strong property rights and strong institutions to protect those rights.

This table is instructive. The top half has the top seven countries by their rank for the protection of property rights in 2020 and their reforestation rate from 1990 to 2020. The bottom half has seven of the bottom eight countries in the international property rights index (the exception of Yemen which hardly has any trees at all!) and their reforestation rates which are negative – in almost all cases, they have high levels of deforestation.

| Country | Property rights rank 2020 | Reforestation rate (%) 1990-2020 |

| Finland | 1 | 2.4 |

| Switzerland | 2 | 10.0 |

| Singapore | 3 | 6.7 |

| New Zealand | 4 | 5.6 |

| Japan | 5 | -0.1 |

| Australia | 6 | 0.1 |

| Netherlands | 7 | 7.3 |

| Country (Yemen – bottom country has not been included) | Property rank index 2020 – places from bottom | Reforestation rate 1990-2020 (%) |

| Venezuela | 1 | -11.1 |

| Bangladesh | 2 | -1.9 |

| Nigeria | 3 | -18.5 |

| Madagascar | 4 | -9.2 |

| Zimbabwe | 5 | -7.3 |

| Nicaragua | 6 | -46.7 |

| Pakistan | 7 | -25.3 |

The second table just looks at those South and Central American countries for which there are data and ranks them by security of property rights and levels of reforestation (so a higher rank means higher levels of reforestation or lower levels of deforestation).

| Property rights index 2007 | Reforestation rank – (higher means higher reforestation or lower deforestation) |

Examples reforestation 1990-2020 % |

|

| Uruguay | 3 | 1 | 155% |

| Dominican Republic | 10 | 2 | |

| Chile | 1 | 3 | |

| Costa Rica | 2 | 4 | 4.00% |

| Peru | 9 | 5 | |

| Mexico | 7 | 6 | |

| Panama | 4 | 7 | |

| Colombia | 5 | 8 | |

| Honduras | 13 | 9 | -9% |

| Haiti | 19 | 10 | |

| Venezuela | 18 | 11 | |

| Bolivia | 17 | 12 | |

| Ecuador | 11 | 13 | -15% |

| Brazil | 6 | 14 | |

| El Salvador | 14 | 15 | |

| Argentina | 8 | 16 | |

| Guatemala | 12 | 17 | |

| Paraguay | 15 | 18 | |

| Nicaragua | 16 | 19 | -47% |

| pearson rank correlation coefficient |

0.6 |

There is high correlation between protection of property rights and reforestation levels. Even the exceptions are instructive. Although the Dominican Republic has a poor record in general for the protection of property rights, it has had a focused, government-led scheme to protect and promote forest growth. Government intervention can work in this field but, in general, it is the package of institutions (private property rights, well-functioning and uncorrupt courts and criminal justice systems, and an efficient state operation for where government intervention is needed) that is necessary.

More generally, private property rights are not a panacea. There may be limited situations in which governments should legitimately intervene to protect natural resources that a private owner might destroy for commercial or other reasons. However, such particular interventions are far more likely to be effective if they take place in a situation in which there are effective legal institutions for the protection of property rights more generally.

This reasoning applies to all environmental resources – forests, the conservation of water, the conservation of fish and ensuring that farming is sustainable. Effective protection of property rights is a vital stepping stone to promoting good environmental outcomes. Iceland, for example, has transformed its fishing grounds by establishing private property rights in fisheries. More generally, good institutions, the rule of law and private property are the foundations of harmonious and prosperous societies.

Catholics often cite St. Thomas Aquinas’s justifications for private property. He argued that: ‘Private property encourages people to work harder because they are working for what they would own’. It is a short step from that to the related: ‘Private property encourages people to conserve environmental resources because they are looking after and conserving property, the fruits of which efforts they will own’.

If we wish to tackle deforestation (or the degradation of many other environmental resources), we need to examine a range of institutions related to property rights. As Pope John Paul II put it in Centesimus Annus: ‘Economic activity, especially the activity of a market economy, cannot be conducted in an institutional, juridical or political vacuum. On the contrary, it presupposes sure guarantees of individual freedom and private property, as well as a stable currency and efficient public services. Hence the principle task of the State is to guarantee this security, so that those who work and produce can enjoy the fruits of their labours and thus feel encouraged to work efficiently and honestly. The absence of stability, together with the corruption of public officials and the spread of improper sources of growing rich and of easy profits deriving from illegal or purely speculative activities, constitutes one of the chief obstacles to development and to the economic order.’

Philip Booth is professor of finance, public policy, and ethics and director of Catholic Mission at St. Mary’s University, Twickenham (the U.K.’s largest Catholic university). He has a B.A. in economics from the University of Durham and a Ph.D. from City University.

Philip Booth is professor of finance, public policy, and ethics and director of Catholic Mission at St. Mary’s University, Twickenham (the U.K.’s largest Catholic university). He has a B.A. in economics from the University of Durham and a Ph.D. from City University.

Reasoning Robots

It was announced recently that developers of artificial intelligence models at Meta are working on the next stage of ‘artificial general intelligence’, with a view to eliminating mistakes and moving closer to human-level cognition. This will allow chatbots and virtual assistants to complete sequences of related tasks and was described as the beginning of efforts to enable AI models to ‘reason’, or to uncover their ability to do so.

This represents a significant advance. One example given, of a digital personal assistant being able to organise a trip from an office in Paris to another in New York, would require the AI model to seek, store, retrieve and process data recognised as relevant to a task. It would have to integrate ‘given’ information (for instance, the destination and the planned time of arrival), with stored information (such as the traveller’s home address) and search for new information (flight durations, train timetables and perhaps the morning’s traffic reports, for example), which it would have to select as relevant to the task of organising the journey. Following processing of the data, it would then have to instigate further processes (such as making reservations or purchasing tickets with third parties).

Human Reasoning and Moral Problems

Remarkable as such a development is, the concept of ‘reasoning’ in play is limited. Compare this to the kind of reasoning of which human beings are capable, particularly in morally ‘difficult’ situations.

Consider the case of someone who, while shopping in a supermarket, catches sight of a toy that he knows his daughter would love for her birthday, but which, down on his luck, he is unable to pay for. The thought crosses his mind that he could simply make off with it. He might think about how this is to be done. Maybe he could run through the door with an armful of goods before the security personnel have time to intervene. This is not certain to succeed, particularly if there are staff outside who might be alerted. Even if he escapes, he is still likely to have been recorded by in-store security systems and having drawn attention to himself by his flight, he risks identification and subsequent arrest. Perhaps, then, he could just hide the toy in his coat, or even use a self-service checkout but fail to scan some of the items that he wishes to leave with. He might then wonder whether he should steal. On the one hand, having lost his job some weeks ago and having been unable to find work, he is very short of money and he has children to feed – and there is a birthday coming; on the other, should he be arrested, he risks punishment under the law, which will in all likelihood worsen his family’s situation. Perhaps he will then consider whether he has any right to act in the manner that he has been considering, reflecting on whether his level of poverty justifies what he had been intending to do. The supermarket chain makes millions in profits every year, while he is only trying to provide for his family and make his daughter happy – and with an item that the shop probably won’t even miss. Ultimately, a consideration of principle alone – a conviction about the general immorality of theft – leads to a resolve to return some of the food items to the shelf, put the toy in his basket and to pay for everything he has selected.

Recognising Reasons

In this case, the subject has undoubtedly engaged in reasoning of an interesting and complex variety. First, it should be noted, the man has not processed data, but considered reasons. Moreover, he has considered not only a number of reasons, but reasons of different kinds. He has moved from an initial motive based on a desire (to please his daughter), through considerations of possible means and outcomes, to issues of familial obligation, distributive justice and moral principle. He has even considered both prudential and moral questions in relation to the matter of whether he ‘should’ steal. Just as easily, he could also have reflected on questions of political obligation and his duty to obey the law.

There are two points of importance here. The first is that in spite of their differences – a concern about the consequences of arrest for one’s family being different in kind from a speculation about the material injustice of one’s situation – the agent was able to recognise the relevance of these considerations as reasons. The second is that of all of the reasons under consideration, his action was ultimately motivated by a single consideration of a moral nature.

It is clear from this example that reasoning (at least as it relates to questions about how to act) extends far beyond calculation or processing data in order to reach a defined end. The man did not follow a set process to reach a pre-determined goal. Indeed, part of his dilemma involved reflection on what the goal should properly be, such that there was even reasoning about the desirable outcome. (He might, for instance, have decided to complete his shopping and leave the toy on the shelf, in the hope that it might soon be reduced in price.) Moreover, owing to the ‘qualitative’ differences between the reasons that he considered, he did not simply ‘pile them up’ and reach a decision based on a form of ‘difference calculation’. Indeed, it is not obvious that there is any intelligible sense in which one could ascribe a calculable ‘value’ either to the man’s conviction that stealing was wrong, or to his desire to please his daughter.

The Requirements of Reasoning

These two points reveal some important characteristics of human reasoning about action. The ability to deliberate about what constitutes a (good) reason for acting and to decide which reasons ultimately matter requires consciousness. This is surely one of the differences between data and reasons. Unlike machines processing data, we are aware of our reasons. Moreover, they have meaning for us, usually in relation to a projected aim or in light of our values – and quite often both. (The fact that a shop has CCTV, for instance, becomes meaningful if one is considering or planning theft.) In order for the man to reach the decision he did, he had to be aware of various reasons and to admit the overwhelming salience of the moral conviction that ultimately held sway because it meant more than the others. (To say that it ‘meant more’ is not to say that each reason has a measure of ‘meaning’ and that the moral consideration ‘weighed’ more than the others. This would be to reintroduce the idea of ‘calculation’. Rather, the moral consideration was a reason of a different kind and had a particular importance. Indeed, it is often the case that moral convictions will limit the courses of action that we are prepared to consider, such that a different person in a similar situation would not even have entertained the possibility of stealing.)

Thus, we are conscious of reasons and adopt them as the ground of our actions, such that they are usually realised or expressed in what we do. The fact that we are conscious of reasons and acquiesce in them when we act is what makes them reasons rather than causes: they are our reasons and make our actions meaningful. This is what renders our actions actions, rather than mere ‘behaviour’. In addition, they make our actions ours, such that we are responsible for them. This is why AI models functioning on data, without consciousness, cannot be considered agents and are not themselves deemed to be morally responsible.

Reasoning and Processing

Following a process or executing a calculation are of course central to certain types of reasoning, but it is doubtful whether in themselves they should be described as reasoning. Properly speaking, this surely requires consciousness. Where a student successfully solves an equation using a prescribed formula, but without understanding what is being done, what the formula achieves, why the answer is right or what it means, would we say that he or she had ‘reasoned’? This is debatable, but the student is conscious, has a concept of what equations are and grasps the notion of number. The tasks of which the most advanced AI models are soon to be capable will be completed without any conscious awareness of the task to be fulfilled or the meaning of the data deployed. This is not to denigrate what artificial intelligence is able to achieve: the technology is advancing quickly and with impressive results. In the absence of consciousness, however, its remarkable capacities might better be referred to as processing or calculation rather than ‘reasoning’ at all – and without reasons, it remains a long way from true human-level intelligence.

Neil Jordan is Senior Editor at the Centre for Enterprise, Markets and Ethics. For more information about Neil please click here.

On Thursday, 23rd May 2024 the Centre for Enterprise, Markets & Ethics (CEME) hosted an online event on the topic of Artificial Intelligence: Challenges and Opportunities.

The event was chaired by Revd Dr Richard Turnbull and our speakers were:

On Saturday, February 10th, in Chinatown in San Francisco, a crowd of people attacked and burnt a driverless car operated by Waymo (Google’s self-driving car project). This represents an escalation of activism against autonomous vehicles led by a group calling itself the Safe Street Rebels, who generally seek to disable driverless cars by placing a traffic cone on the bonnet (or hood, for our American readers), which renders the vehicle immobile until a company employee can attend to it. The group’s website expresses a variety of grievances regarding the introduction of autonomous vehicles on public roads, among them being claims regarding increased congestion, safety, surveillance, lack of accessibility and a dearth of legal accountability. Taken together, they amount to a moral case against driverless cars, but each one of the arguments is potentially capable of being addressed by way of advances in technology, the introduction of new legislation or changes in the conduct of the companies that operate driverless cars. There are, however, other arguments to consider – ones that focus less on from the practicalities, dangers and risks of AI controlled vehicles as they currently stand, and more on the value of human capacities and skill.

Traffic, Legislation and Accessibility

The argument that driverless cars (particularly robotaxis) encourage the use of individual vehicles rather than other forms of mobility is salient, particularly in cities that already suffer from congestion and in which there are concerns about air quality (as well as pollution more generally), but this is really an argument about our transport decisions more broadly and is not specific to driverless cars. That is to say, it is an argument against introducing more private transport, rather than specifically autonomous private transport. Similarly, the assertion that autonomous vehicles are exempt from citations for certain motoring offences (a result of the assumption in existing legislation that vehicles have drivers) could easily be addressed via the introduction of laws that treat as drivers either the safety operators present in certain cars or the companies that operate them, who can therefore be held culpable for traffic violations. (Safety operators are already liable to prosecution, as demonstrated by the charges brought against one such driver after a fatal accident in Arizona.) It is contended that self-driving cars are not accessible for those with disabilities. There do indeed seem to be problems with their ability to pull over to the kerb to pick up passengers. Operators are under pressure to rectify this issue (not least because their tendency to stop in traffic lanes creates obstructions) but on the matter of accessibility for those who use wheelchairs, Google suggests that accessible cars can be summoned, with safety operators to assist passengers. Not all driverless vehicles are accessible, but it could be argued that this issue is being addressed.

Surveillance and Sales

Two fundamental concerns are connected with surveillance and safety. With regard to the former, driverless cars do collect various types of data, whether connected with location and the journey itself, or information about passengers. The sensors on the car will also record information about journeys, including objects encountered in the course of travel, such as other cars, humans or animals, such data being necessary for improving safety and avoiding collisions. The use of this data is an area of legitimate concern. If this information is passed to authorities, people can rightly be worried about invasions of privacy and the growth of the surveillance state. Moreover, as Matthew Crawford argues in Why We Drive: On Freedom, Risk and Taking Back Control, citing in this regard the importance of Shoshana Zuboff’s work on surveillance capitalism, it is also quite possible that the technology firms developing driverless cars will be able to use passenger data in order to build a user profile and employ it for the purposes of ‘managing’ more of our activity and selling products and services to users – data being a valuable commodity in contemporary capitalism. This is of course a risk associated with advancing technology but need not be an argument against autonomous vehicles themselves. After all, there are concerns about the extent to which smart TVs and even Alexa devices record information about users. Were technology companies to behave differently, or were there to be rigorous data protection laws in place – laws which were actually enforced with penalties for companies found in breach of them – perhaps the capture, storage and use of data needn’t be of such concern.

Safety

Quite reasonably, safety is the fundamental reason for opposing the introduction of self-driving cars. There have been numerous incidents involving such vehicles. As a result of one fatal accident, Uber ceased testing autonomous vehicles in Arizona, while in the wake of a serious collision, Cruise, a subsidiary of General Motors, had its test licences revoked by the regulator (the DMV) in California on the grounds of ‘unreasonable risk to public safety’. Until such time as deaths and injuries caused by driverless cars can be avoided, it is quite proper to argue that such vehicles should not be on public roads. This is an argument based on the current state of technology rather than driverless cars per se. Without fundamentally redesigning cities and traffic management, there are good reasons to doubt whether self-driving cars will ever be completely safe – or at least no less safe than cars driven by humans – but should the technology ever advance to this point, this argument would no longer serve as a reason to keep autonomous vehicles off public roads.

Driving as a Skill

So far, all arguments, though compelling in their own way, are in a sense ‘time-limited’ and stand to lose their force were suitable changes to occur in legislation, technology or the behaviour of companies. However, an argument advanced by Crawford is rather more stubborn in the face of such changes because it is centred not on the state of technology or regulatory frameworks, but on the nature of driving itself, and human beings as drivers. This argument states that in a world in which driverless cars are the norm, we are rendered (even more) dependent on technology companies, thus impoverishing us as human beings. Much technology – dishwashers, for instance – has the advantage of freeing us from mundane chores to focus on other, more rewarding or fulfilling tasks. Autonomous vehicles are not like this. Driving is not like washing up: it is a skill that requires judgement and the honing of certain capacities, including the ability to negotiate solutions with other road-users to emergent situations through the use of accepted social cues (a feat that it is hard to see autonomous vehicles ever achieving). Driving grants us autonomy and (in some cases) enjoyment but is also a learned ability. Stripping us of this and replacing it with a form of automated transport, controlled by large companies, is to deprive us of something worthwhile and valuable.

Value and Flourishing

It might be replied that driving simply isn’t important: after all we don’t object to not being allowed to drive trains when we catch them. This is true, but it does not address the value of an acquired skill and its place in human flourishing. As we read about the capacity of AI to generate poems, we might wonder whether, at some point, the technology will be able to produce material comparable to that of the greats. Would we equally argue that since software can create poetry that is every bit as impressive as that written by a human, then humans might just as well give up poetry? Surely the answer is that we should not: a skill, an ability or an excellence, provided it is not in some way intrinsically disordered, is of value and is worth preserving. Driving might not be as rarified as great poetry (though Formula 1 aficionados might beg to differ) but this does not make it valueless. Being able to execute a three-point turn might not be an achievement comparable to the work of Thomas Hardy or Virgil, but it is also true that most poetry is not of this kind either. If a computer can produce a poem that is ‘better’ than that of a primary school child, should we simply leave poetry to the software and, once the children have decided on the subject, set them some other task while the computer writes the poem for them? Most would think not – because even if a skill is one in which we are not expertly proficient, or is less impressive than some other activity we might attempt, it can still quite properly be considered worthwhile and a ‘good’.

Conclusion

Were driverless cars to become so advanced that they had almost no environmental impact, were entirely accessible, were never involved in accidents and were subject to laws of the road just like human drivers; were the operating companies to work within a strict social and moral code; and were regulations to prevent the misuse of data always and everywhere enforced, there would still be the question of whether, in dispensing with cars driven by humans, we were in some (perhaps small, but still significant) way, having an adverse effect on human flourishing. This is a moral consideration for us to ponder.

Photograph ©Robin Hamman, downloaded from Flickr using a CC BY-NC 2.0 Deed creative commons licence.

Neil Jordan is Senior Editor at the Centre for Enterprise, Markets and Ethics. For more information about Neil please click here.

What are the lessons we can learn from Wilberforce today? What about the continued challenges of modern slavery? The Centre for Enterprise, Markets and Ethics, together with CCLA, hosted an event on the topic on the 24th April 2024.

Our speakers were:

Revd Dr Richard Turnbull: Lessons from Wilberforce’s campaign against the slave trade

Dame Sara Thornton: Insights from the fight against modern slavery

The event was chaired by Alderman Robert Hughes-Penney.

An Introduction to William Wilberforce written by Richard Turnbull

This paper is part of a series of essays that seek to explore the current and prospective impact of AI on business. A PDF copy of this paper can be accessed here.

The advent of Generative AI is challenging and redefining the world of work. While exacting data on its impact remain at a nascent stage, a growing number of private firms and research organisations have been quick to impart their early predictions. McKinsey & Co. estimates that Generative AI could add as much as $4.4 trillion to the global economy annually, leading to profound changes in the anatomy of work, with an increase in both augmentation and automation capabilities of individual workers across all industries.[1] Goldman Sachs believes that Generative AI could raise global GDP by as much as 7% with two-thirds of current occupations being affected by automation.[2] At the macro level AI is poised to reshape the strengths of nation-state economies. Research conducted by Oxford University and CITI Bank found that ‘The comparative advantage of rich nations will increasingly lie in the early stages of product life cycles — exploration and innovation rather than execution or production — and this will make up a bigger portion of total employment. […] Without innovation, progress and productivity will stall’.[3]

In September 2023 Microsoft launched ‘Copilot 365’, an AI-driven digital assistant that integrates Office applications such as Word, Excel and PowerPoint to enable the user to harness the capabilities of AI within their workflow. Copilot and other AI agents such as Google’s ‘Gemini’ aim to combine the use of Large Language Models (LLMs) and user generated data to greatly enhance productivity. Microsoft Chairman and CEO Satya Nadella said that ‘[Copilot] marks the next major step in the evolution of how we interact with computing, which will fundamentally change the way we work and unlock a new wave of productivity growth. […] With our new copilot for work, we’re giving people more agency and making technology more accessible through the most universal interface — natural language’.[4]

These potentially seismic changes urge us to reconsider the fundamental nature of work. They force us to step back and ask how ought humanity shape its future relationship with work. This implicitly raises wider questions of purpose, meaning and a sense of calling that pervades the mere temporal dimension of work. From a Judaeo-Christian perspective it seeks a re-evaluation of the gift and place of human agency and responsibility within creation.

The argument of this paper is therefore twofold. First, we point out that that all technological advancements, including Generative AI, should be harnessed for the benefit and enhancement of humanity. This applies in particular to work but should not be excluded from other spheres of human endeavour such as leisure or recreation. Second, we point out that, while most technological advancements are valuable, a careful and persistent degree of discernment needs to be applied in minimising the novel risks brought on by Generative AI. A central concern here is the capacity for misuse of AI (with the various facets that may entail), as well as the long-term risk that it presents of a destructive and dehumanising effect on its users.

Defining the Terms

It is worth starting with a brief conceptual analysis of some of the key terms. What do we mean by ‘work’? How are we to delineate a ‘humanising’ versus ‘dehumanising’ effect on work? Indeed, are we mistaken in assuming any intrinsic value of work in the first place? These are all pertinent questions that require much thought and attention.

In his monograph on Recovering a Theology of Work, Revd Dr Richard Turnbull rightly points out that work ’…is not a static concept’.[5] Work evolves in tandem with the ability of humans to learn, pursue and engage with it, which implies an ongoing relational change in both skill and knowledge. This creative ability is, for the Christian theologian, a reflection of the Imago Dei that is fundamental to all of humanity. Darrell Cosden, who wrote extensively on the theology of work acknowledges that ’work is a notoriously difficult concept to define’.[6] Cosden views human work as ’a transformative activity essentially consisting of dynamically interrelated instrumental, relational, and ontological dimensions’.[7] Work is therefore a multifaceted concept.

If we step back for a moment and consider a more utilitarian interpretation we find some rather crude definitions of work. The Cambridge dictionary sees it as ’an activity, such as a job, that a person uses physical or mental effort to do, usually for money’.[8] In pure physics work is ’the transfer of energy by a force acting on an object as it is displaced’.[9] This apparent dichotomy leads us to (at least), two broad and distinct dimensions of work: 1. The physical or mental activity that usually results in quantifiable economic activity; 2. Work in relation to meaning (or semantics), the presence of a personal calling and a higher purpose that serves as an ultimate goal.

Attempts to categorise the term ‘humanising’ are also likely to encounter an additional array of definitional challenges. Some dictionaries see it as ‘representing (something) as human: to attribute human qualities to (something)’,[10] others define it as ‘the process of making something less unpleasant and more suitable for people’.[11] The common denominator in attempting to describe ‘humanising’ is the intention to give something qualities that make it suitable for humans to use and understand – an effort which in and of itself no doubt suffers from a degree of subjectivity.

The last major term that we will attempt to define is ‘Generative Artificial Intelligence (AI)’. I have written elsewhere about the concept of intelligence and how it fits within AI, so a detailed discussion on the matter will not be included here. However, what is worth mentioning is that by ‘Generative AI’ we are referring to complex yet narrow AI systems that currently exist or at most are likely to emerge within the short to medium term (3-5 years). By ‘generative’ we are referring to AI systems that not only learn from new data but generate interpretable results based on said data – this includes LLMs such as ChatGPT3/4, LaMDA, Google Gemini and so on.

The Impact of Generative AI

There are competing narratives as to which technological changes of the modern era bear the greatest impact on work and productivity. The British Agricultural revolution of the 17th and 18th centuries saw a dramatic increase in crop yields and agricultural output which resulted in the population of England and Wales almost doubling from 5.5 million in 1700 to over 9 million by the end of the century.[12] The arrival of the steam engine in the second half of the 18th century and the subsequent mechanisation of labour sparked the first and second Industrial Revolutions. The change to the nature and purpose of work during this time was fundamental. Europe moved from a largely agrarian-based society to one that was driven by mass production, standardisation and the development of new skills and abilities in manufacturing and scientific discovery.

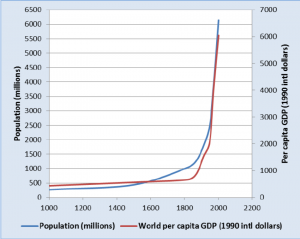

One remarkable chart worth revisiting is illustrated in the adjacent figure.[13] For over 1,800 years GDP per capita remained largely flat – and only changed in the late 19th century when both GDP per capita and global population experienced a sudden and unprecedented jump in both trajectory and scale. The change was overwhelmingly attributed to the transition of a workforce that had previously been accustomed to hand manufacturing and production to becoming almost entirely machine-driven. This in turn, allowed for more effective and precise tools, a greater understanding of chemicals and alloys, and widespread availability of these to workers that previously relied solely on manual labour. Some economic historians such as Paul Bouscasse et al. (2021) estimate that the Industrial Revolution quadrupled average productivity by each decade, from around 4% up until the 1810s to over 18% from there onwards.[14]

One remarkable chart worth revisiting is illustrated in the adjacent figure.[13] For over 1,800 years GDP per capita remained largely flat – and only changed in the late 19th century when both GDP per capita and global population experienced a sudden and unprecedented jump in both trajectory and scale. The change was overwhelmingly attributed to the transition of a workforce that had previously been accustomed to hand manufacturing and production to becoming almost entirely machine-driven. This in turn, allowed for more effective and precise tools, a greater understanding of chemicals and alloys, and widespread availability of these to workers that previously relied solely on manual labour. Some economic historians such as Paul Bouscasse et al. (2021) estimate that the Industrial Revolution quadrupled average productivity by each decade, from around 4% up until the 1810s to over 18% from there onwards.[14]

Large-scale industrialisation and the rise of the mechanised factory system created fertile ground for what would later become the digital revolution (i.e. the Third Industrial Revolution). The middle of the 20th century saw the arrival of the first transistor which not only paved the way for modern computing, it more fundamentally enabled the digitalisation of information. This marked a major change in the way in which information is stored and shared, and perhaps unsurprisingly, at least in retrospect, also brought profound changes for the world of work. The first through third Industrial Revolutions represent magnificent events of human advancement that altered the course of history in ways that make the absence of their fruits in contemporary life hard to imagine. Therefore, how would Generative AI fit within such a paradigm?

The scholastic body of research in this area is embryonic. The ‘Fourth Industrial Revolution’ or ‘Industry 4.0’ coined back in 2013 by former German Chancellor Angela Merkel foresaw a future where the collective power of technologies such as AI, 3D Printing, Virtual Reality (VR), the Internet of Things (IoT), and others could be integrated and used within a (predominantly) unified system.[15] Over a decade later this holistic vision has yet to fully materialise. What we are currently seeing are many of these technologies being largely used in silos rather than fully integrated systems (with a few exceptions such as smart homes). In 2020 a KPMG report found that less than half of business leaders understood what the ’fourth industrial revolution’ meant, with online searches of the term having peaked in 2019 and trending downward ever since.[16]

On one level the prophecies of the Fourth Industrial Revolution have yet to be fulfilled. Current research into the impact of AI is therefore reliant upon scarce present data and future predictions that are, more often than not, overhyped and peppered with unlikely outcomes. One more robust piece of research has been an intercollegiate effort between academics at the universities of Leeds, Cambridge and Sussex, which found that 36% of UK employers have invested in AI-enabled technologies but only 10% of employers who hadn’t already invested in AI were planning to do so in the next two years.[17] Commenting on the research, Professor Mark Stuart, Pro Dean for Research and Innovation at Leeds University Business School said that,

’A mix of hope, speculation, and hype is fuelling a runaway narrative that the adoption of new AI-enabled digital technologies will rapidly transform the UK’s labour market, boosting productivity and growth. However, our findings suggest there is a need to focus on a different policy challenge. The workplace AI revolution is not happening quite yet. Policymakers will need to address both low employer investment in digital technologies and low investment in digital skills, if the UK economy is to realise the potential benefits of digital transformation.’[18]

These apparent roadblocks will require a concerted effort on behalf of employers and employees to actively seek and develop new skills that will give organisations the capabilities required to meaningfully integrate AI systems into their workflows. As has been the case with the industrial revolutions of the past, new technologies invariably necessitate new knowledge and training. AI Prompt Engineering is an interesting example of this. Although Large Language Models (LLMs) are built to operate via NLP (Natural Language Processing), they still require specialised training when dealing with more complex challenges or troubleshooting errors. A ‘Prompt Engineer’ in this sense is a trained professional that creates ‘prompts’ (usually in the form of text), to test and evaluate LLMs such as ChatGPT.[19] Thus, a well-trained prompt engineer can extract and gain far more from LLMs than the average user.

More importantly, the skills and capabilities gap between AI systems and the end-user need to be bridged in a manner that allows for the concurrent growth of the technology as well as the flourishing of the workforce. This is all the more pertinent when we are talking about a workforce that is predicted to become increasingly reliant on AI. What generative AI has achieved thus far is to fuel a creative springboard that enabled a wider audience to imagine the possibilities (and risks) of AI tools: ranging from relatively banal features such as improved email spam filtering to uncovering disease-fighting antibodies. A report by the International Data Corporation (IDC) estimated that the use of conversational AI tools is expected to grow worldwide by an average of 37% from 2019 to 2026.[20] With the accelerated growth of Microsoft’s ChatGPT, Google’s Bard as well as other tech giants joining the conversational AI race, it is reasonable to expect that this figure may end up being higher.

Yet we do not know exactly what impact this will have upon work. There have been some early studies and working papers that suggest that AI tools are having a positive effect on employee productivity. The National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) recently published a paper by Erik Brynjolfsson, Danielle Li & Lindsey R. Raymond which looked at a case study of 5,179 customer support agents using AI tools. The report found that,

‘Access to the tool increases productivity, as measured by issues resolved per hour, by 14% on average, including a 34% improvement for novice and low-skilled workers but with minimal impact on experienced and highly skilled workers. We provide suggestive evidence that the AI model disseminates the best practices of more able workers and helps newer workers move down the experience curve. In addition, we find that AI assistance improves customer sentiment, increases employee retention, and may lead to worker learning. Our results suggest that access to generative AI can increase productivity, with large heterogeneity in effects across workers.’[21]

It appears therefore that while there is an overall increase in productivity, a key factor in its dispersion is dependent upon the varying degrees of employee experience and skill level, with those at the lower end of the spectrum likely to benefit more that those at the top. Another study led by Shakked Noy and Whitney Zhang from MIT looked at an empirical analysis of business professionals who wrote a variety of business documents with the assistance of ChatGPT. The study found that of the 444 participants, those that used ChatGPT were able to produce a deliverable document within 17 minutes compared to 27 minutes for those who worked without the assistance of ChatGPT.[22] This translates to a productivity improvement of 59%. What is perhaps more remarkable is that the output quality also increased: blind independent graders examined the documents and those written with the help of ChatGPT achieved an average score of 4.5 versus 3.8 for those without.[23] A third preliminary study looked at the impact of ‘GitHub Copilot’, an AI tool used to assist in computer programming. The paper found that programmers who used GitHub Copilot were able to complete a job in 1.2 hours, compared to 2.7 hours for those who worked alone. In other words, task throughput increased by 126% for developers who used the AI tool.[24]

Pursuing a Theology of Work

This provokes some wider questions surrounding morality, AI and work. One pertinent question here is not just a matter of can we use AI but rather how ought we to use AI? Indeed, how are we to best integrate AI in manner that reaps the rewards and minimises the risks? If we consider the Judaeo-Christian perspective, the obligatory prerequisite to answering these questions is a scriptural understanding of the act and role of work.

In the Old Testament we find several fundamental passages in relation to work. The first and perhaps most widely cited is Genesis 1:28 and 2:15 where humanity is called to ‘Be fruitful and increase in number; fill the earth and subdue it. Rule over the fish in the sea and the birds in the sky and over every living creature that moves on the ground. […] The Lord God took the man and put him in the Garden of Eden to work it and take care of it.’[25] The command here is not just one of stewardship over creation, but a calling to reflect through human capacities that which is teleologically divine: the ability to order, create, tend to, and indeed destroy (within the premise of the fall).

God himself is portrayed as a worker: ’In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth’ (Gen. 1:1), and then in Genesis 1:27 we find that God ’created man in his own image’.[26] In this sense human work is fundamentally ’…derived from the principle of God’s work in creation’.[27] While humanity is called to mimic God’s creative pursuit, it also has the responsibility to protect and care for the gift that is creation and everything found within it. Genesis 2:15 portrays the garden as an adequate place where man can fulfil his duty and calling of work. David Atkinson in his commentary usefully points out that ‘…work is not simply to be identified with paid employment. Important as paid work is in our society, both in providing necessary conditions for adequate living standards, and in giving a person a sense of worth in his or her creativity, it is the creative engagement with the world on behalf of God that is the really significant thing’.[28] This rather Barthian perspective gives significance to work in as much as it represents a conscious partaking in the establishment of God’s kingdom through Christ. The objective is, according to Barth, ‘…the centre of God’s activity. [..] [so] the centre of our human actions as Christians must be to reflect this focus on the kingdom of God’.[29] Work therefore encapsulates the temporal and the metaphysical. Human action is not merely a bystander to the cosmic order of events but an active partaker in shaping the journey. The Genesis account of creation therefore does not delineate between secular and pious work – all work in the garden carries some degree of spiritual value. It is important to note that the distinction between the sacred and the secular in the first place can only be made in light of the fall.

This raises another key dimension in developing a theology of work, that is, the notion of calling and vocation. For Martin Luther there are two kingdoms: the temporal and the eternal. Human endeavour operates entirely within the temporal but the tension between good and evil (or sin) cuts through and is present in both, making the struggle omnipresent. The act of human calling and vocation in the temporal therefore becomes as important and relevant as it is in the eternal. There is a continuous interplay between the two, as Richard Turnbull notes: “there is no dualism here in Luther. Vocation and calling, ethics and behaviour are the ways God is served in the temporal kingdom”.[30]

If we turn to the New Testament we find a series of examples where so-called ‘secular’ work is used to advance the heavenly kingdom. In Acts Chapter 16 we are introduced to Lydia of Thyratira, a businesswoman in what was considered those days to be expensive clothing or ‘purple cloth’ (verse 14). We are told that Lydia persuaded the apostles and used her earned resources to care and provide for Paul and Silas: ‘If you consider me a believer in the Lord,’ she said, ‘come and stay at my house’ (verse 15). Paul himself, though highly educated in the Hebrew law, maintained his work as a tentmaker (Acts 18:3) and used it to not only financially support his ministry but also to minister to others through it:

‘I coveted no one’s silver or gold or apparel. You yourselves know that these hands ministered to my necessities, and to those who were with me. In all things I have shown you that by so toiling one must help the weak, remembering the words of the Lord Jesus, how he said, “It is more blessed to give than to receive.”’ (Acts 20:33-35, RSV)

As a more anecdotal observation, it is interesting to see how Paul, though a scholar, never found himself too proud to undertake manual labour. That was likely driven by his profound understanding of what true Christological self-sacrificial love and service entails – his life as presented in the scriptures embodies it fully.

Peter, Andrew, James and John were the first disciples called by Jesus in Matthew 4:18–22. By most historical accounts they were ordinary fishermen operating within a highly competitive fishing environment that were the shores of Galilee in the 1st Century A.D. It is reasonable to assume that they possessed some degree of business acumen in budgeting, preparing orders, managing stocks and so on. Indeed, Jesus himself worked as a carpenter in his family business (Mark 6:3) and one can imagine that Joseph (and likely Jesus himself) had to utilise their skills and knowledge in budgeting, drawing projects, analysing space, preparing materials and fulfilling orders to clients – there is no suggestion in scripture that this was a pro bono affair.

Neither Jesus, nor any of the disciples shied away from what would today be labelled as ‘secular work’. Quite the contrary, they embodied work as: 1. An integral part of their calling before God in the temporal; and 2. A fulfilment of their God-given gifts and abilities in utilising and developing the skills needed to carry out the work. Indeed, Christ vividly illustrated the implications of this aspect in the Parable of the Talents found in Matthew 25:14–30 and Luke 19:11–27.

Conclusions: Towards a collaborative theology of work and AI?

In the introduction we mentioned the necessity and overarching aim that all technological advancements, including Generative AI, should be harnessed for the benefit and enhancement of humanity. This applies in particular to work but also to other spheres of human activity such as family time or recreation. It is also important to note that great care and discernment needs to be applied in minimising the novel risks posed by Generative AI, such as an unhealthy reliance on the technology, disinformation, fraud, and so on. Discernment in this case refers to uncovering the right way of action amidst uncertainty.

We have also seen how Judaeo-Christian teaching places the concept of Work as a key part of what it means to be made in the image of God and to actively partake in the eschatological realisation of creation. If work therefore represents an integral element of Christ’s redemptive transformation of the individual (and indeed the world), how does AI fit within this paradigm?