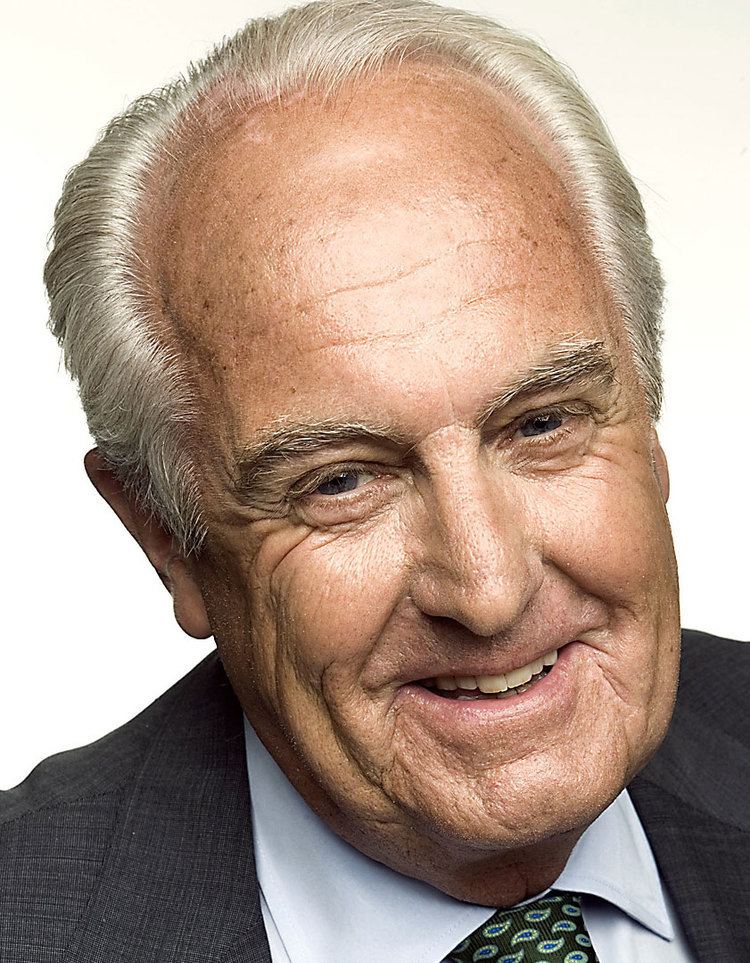

Steve Morris: Lost gurus of the 80s – Jan Carlzon (Part 2: The Heart of Leadership)

Jan Carlzon, the dynamic architect of the rescue of Scandinavian Air Services in the 80s, had a good deal to say about what it is to be a leader. We would do well to listen because he counters some of the common misconceptions about leadership.

One of those things is that the leader should always be busy, available and there to solve every problem. How many times has a government minister or even the Prime Minister been called back from holiday because they have to be there to sort something out? I almost feel sorry for them. For goodness sake let them have a few days off and let other people do some of the work.

The image of the superhero leader who never gets tired, is always available on the end of his or her phone is deeply destructive because it leads in the end to people who burn-out and organisations that are so heavy at the top that those who are doing the job feel they have no power.

Carlzon begins his dissection of leadership with an interesting story. In the summer of 1981, the first year he became president of SAS, he decided to take two weeks holiday. As soon as he got to the country house, the telephone began ringing. It rang so much over the first couple of days that he gave up on his holiday and returned to Stockholm. The following summer a Swedish newspaper interviewed him on the subject of taking it easy. He agreed but only if the article was published a week before his own vacation so that everyone in SAS read it and knew what he had to say.

In the interview Carlzon explained that he believed responsibilities should be delegated within a company so that the decisions are made right at the moment of truth, the place where they need to be made. The higher up decisions need to be referred in the organisational chart the more likely it is that people won’t take responsibility and those at the top won’t be able to take a holiday. In the article, he explained this and said that he intended to take four weeks holiday and would see his telephone not ringing as proof that he was succeeding.

As a leader it’s always good to feel wanted and relevant but we need to know that this kind of hero leader is not sustainable Carlzon talks about his earlier experience at a smaller airline where he tended to take every single decision. He came to the realisation though, that a leader is not appointed because he knows everything and makes every decision; he’s appointed to bring together the knowledge that’s available and then create the circumstances in which people can be successful . Delegation is key to leadership and that means delegating whole tasks not just parts of them.

Carlzon argues that what’s needed is a leader who has a helicopter sense, a talent for rising above the details to see how the land is laying. Today’s business leader needs to understand finances and production and technology but must also be an expert in human resources. The leader therefore helps to set the culture of the organisation – the way things are done around here.

Carlzon’s view of leadership is far more than utopianism. It is nuanced. He admits there are some areas in which the leader has to be an enlightened dictator. They must, without variance, explain convincingly the vision and the goals and strategies so that everyone knows exactly what the company is doing and to keep doing that even when life looks difficult.

The leader has to deal with difficult people and those who don’t agree and give them more information and attempt to make them understand. If people can’t be that persuaded, Carlzon says, the least that can be expected from them is loyalty even if they’re not emotionally committed to the goals. If this isn’t achievable, they should be asked to leave.

Carlson makes it very clear that he’s not calling for corporate democracy in its purest form. He believes that everyone; middle managers, frontline employees, union leaders, and board members must be given the opportunity to air their views, but they are not all involved in making every final decision.

The leader is the one who creates just the right environment for business to be done – not too hands on, not too distant. Carlzon uses a football analogy. The coach is the leader whose job it is to select the right players, ensure that the team go onto the field in the best condition to play a good game, and on the field there is a team captain who is really analogous to the company managers who issue orders and make changes during the match. Most important of all, of course, are the individual players all of whom are their own boss during the game. He asks us to imagine when a player with an open goal suddenly abandons the ball to run back to the bench and ask the coach for orders on how to kick it.

Carlzon argues that it makes no difference who comes up with a good idea, all that matters are the ideas that work which, he says, was one of the key factors in the success of SAS.

Carlzon’s is a deeply challenging and interesting vision of leadership. It is easy to admire. It makes the world look a bit simpler. But there are those circumstances when all the consulting others and training them might not be what is needed. In some circumstances the leader just has to tell us what to do and we just get on with it. But the principle is a good one; that the more the leader’s phone rings, the less people have taken on delegated responsibility.

Steve Morris is the Vicar of St Cuthbert’s, North Wembly, an entrepreneur, and the author of several publications for CEME and beyond including Enterprise and Entrepreneurship, and Lessons from Family Business, both available from the CEME office. He is married, with two children and has three cats. His latest writing, Our Precious Lives, dealing with the power of story-telling is available here.

Steve Morris is the Vicar of St Cuthbert’s, North Wembly, an entrepreneur, and the author of several publications for CEME and beyond including Enterprise and Entrepreneurship, and Lessons from Family Business, both available from the CEME office. He is married, with two children and has three cats. His latest writing, Our Precious Lives, dealing with the power of story-telling is available here.