President Trump has certainly brought the issue to the fore with a bang. Perhaps his attempts at protectionism will show the error in the thinking of the anti-globalists in our own country. We don’t get many controlled experiments in economics. Perhaps this will be one.

The anti-globalisation trend, which is strongly supported by Christians in the US, has been around for ten years or more. Globalisation itself stalled following 2010, went into reverse by many measures (though not all) during the first Trump presidency, the policies of which Biden continued to follow. But things really do look grim now. It should not be thought that this is only a Trump phenomenon – protectionist sentiment is well engrained amongst Republicans and Democrats.

In the 2016 presidential election, Trump said: ‘You go to New England, Ohio, Pennsylvania …manufacturing is down 30, 40, sometimes 50 per cent. NAFTA is the worst trade deal maybe ever signed anywhere’. It is fair to say that he has not changed his view.

Those arguing for tariffs are wrong about whether there is a problem to be solved; wrong about the diagnosis of the problem they perceive; and wrong about the efficacy of their proposed solution to the non-existent problem.

In the same campaign, the left-wing Democrat candidate and Senator Bernie Sanders said: ‘I do not believe in unfettered free trade…We heard people tell us how many jobs would be created…you are now competing against people in Vietnam who make 56 cents an hour minimum wage.’

Reading his comments on Trump’s policies today, he seems simply to want a better ordered version of those policies.

I will leave the huge benefits of globalisation and free trade for another post. It is just worth noting that the development of the modern era of globalisation was coincident with a huge reduction in absolute poverty and the biggest reduction in global inequality the world has ever known.

But let’s go back to Bernie Sanders’ challenge. In responding to this, we effectively answer the concerns of Trump supporters about free trade. How can the US compete with Vietnamese producers paying 56 cents an hour? Surely, US industry will be wiped out, as Bernie Sanders suggests, if the US lets in Vietnamese imports.

The answer to this question is a clear ‘no’. US workers would earn vastly more than Vietnamese workers even if they were to produce garments because US workers are more productive: they have higher skill levels and use more capital equipment.

More importantly, though, US wages are higher than 56 cents because the US produces more valuable things than cheap garments. It makes sense to export other things that are more valuable and import cheap garments.

Free trade means that the US is able to produce goods and services that are more valuable than garments, export those goods and services and use the proceeds from selling its exports to buy garments. US consumers get cheaper goods from abroad and US producers are able to produce things of a higher value than garments. This is why the average income in the US is nearly 30 times that in Vietnam – it is not 56 cents an hour.

Furthermore, we have global supply chains in which countries produce those aspects of a product they are relatively best at producing. If you buy a shirt with ‘made in Vietnam’ on the label, the sewing machinery might have been made in South Korea or Japan, the dye might have been made in Germany, the cotton might come from Egypt, the shipping might be by a Greek firm, the finance and insurance for the shipping might be provided by a US bank, and so on. It is a collaborative effort. It would not benefit anybody if the whole process were ‘insourced’ and the Wall Street bankers had to go to work in garment and dye-producing factories.

There are significant problems in many developed countries, but I would suggest that they are caused much more by demographics (ageing populations), dysfunctional welfare states and the costs of family fragmentation. These are, essentially, religious and cultural problems which we should not blame on economic globalisation.

The US (like the UK), of course, has a large trade deficit: ostensibly, this is the reason for Trump’s tariffs. This deficit is caused by the US government and private sector (like the UK) being net borrowers – just as Germany’s surplus is caused by Germany being a net saver. [In reality, the situation is a little more complicated than this and issues to do with net direct investment, dividend flows, foreign holdings of dollars, and so on are also important.] If a country is a net borrower, it will import more than it exports and consume more than it produces. Tariffs will not change that situation – they will just make the country poorer.

Those arguing for tariffs are wrong about whether there is a problem to be solved; wrong about the diagnosis of the problem they perceive; and wrong about the efficacy of their proposed solution to the non-existent problem.

What is the Church’s position on free trade? Its position arises from her concern for the poor and is not unqualified. Pope Paul VI wrote in Populorum progressio in 1967: ‘trade relations can no longer be based solely on the principle of free, unchecked competition, for it very often creates an economic dictatorship’. This is interesting because Pope Paul is saying that poor countries lose from free trade whereas Trump is arguing that rich countries lose, and poor countries gain. Economists argue that both gain.

Pope Paul VI’s view reflected the ‘developmental state’ theory common in economics in the 1960s. John Paul II took a different view in his encyclical Centesimus annus:

Even in recent years it was thought that the poorest countries would develop by isolating themselves from the world market and by depending only on their own resources. Recent experience has shown that countries which did this have suffered stagnation and recession, while the countries which experienced development were those which succeeded in taking part in the general interrelated economic activities at the international level.

Empirically, this is correct. Even more pertinently for Catholic leaders of richer countries, Pope Benedict wrote of their obligations to poorer countries, in relation to trade, in Caritas in Veritate:

It should also be remembered that, in the economic sphere, the principal form of assistance needed by developing countries is that of allowing and encouraging the gradual penetration of their products into international markets, thus making it possible for these countries to participate fully in international economic life…Furthermore, there are those who fear the effects of competition through the importation of products — normally agricultural products — from economically poor countries. Nevertheless, it should be remembered that for such countries, the possibility of marketing their products is very often what guarantees their survival in both the short and long term. Just and equitable international trade in agricultural goods can be beneficial to everyone, both to suppliers and to customers.

It is difficult to think of any concern about free trade to which the right response is protectionism through tariffs. Putting aside its economic effects, protectionism creates disharmony and destroys relationships. It makes people who should gain from mutual co-operation believe they can gain at the expense of each other: we are already seeing this. Adam Smith taught us how countries gain from co-operation and exchange rather than from stealing each other’s ‘stuff’. We should not need to re-learn that lesson by having to endure the tragedy of ignoring it.

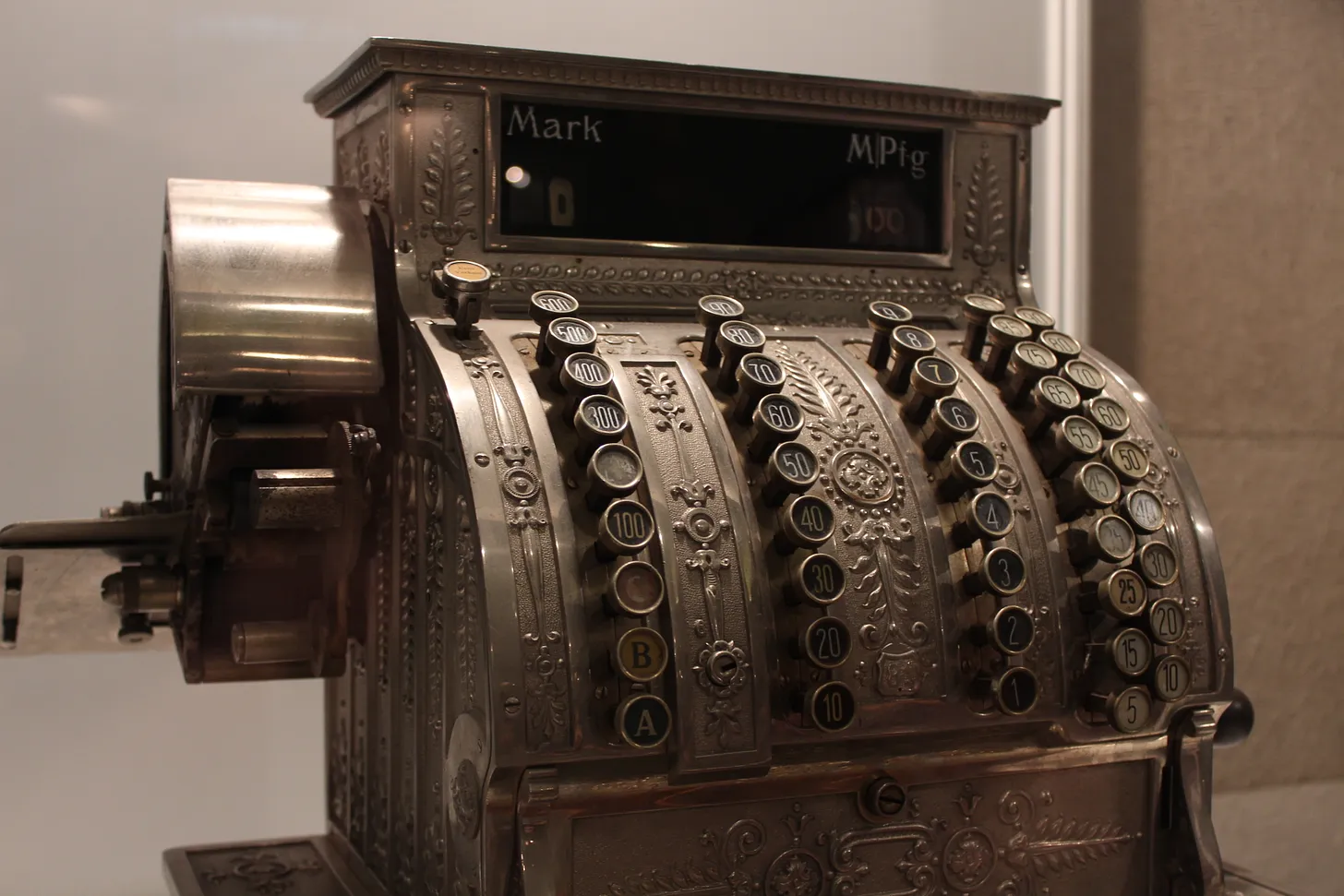

Image: Old cash register in Museum of Technology in Warsaw; reproduced from Wikimedia Commons using a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported licence.