In this discussion with CEME Senior Research Fellow John Kroencke, Andrew Haldane discusses his view that economic growth is a failed lodestar for policy, presents the case for increasing opportunity for those at a disadvantage, and considers the problems with British public finance.

This is the first entry in our Conversations with CEME Series which features a member of CEME in conversation with a leading voice from economics, business, policy, and faith communities to grapple with these defining challenges of our time. Through conversations with experts who approach these issues from diverse perspectives, we aim to explore not just the technical dimensions of our current predicament, but the deeper questions about purpose, meaning, and values that lie at its heart. In an era in which purely economic solutions seem insufficient, these discussions seek to illuminate new pathways forward that acknowledge both the practical constraints we face and the moral imperatives that must guide our response.

The edited transcript follows the introduction to the guest.

Andrew Haldane was the Chief Executive of the Royal Society of Arts (RSA) until June 2025.

He was formerly Chief Economist at the Bank of England and a member of the Bank’s Monetary Policy Committee. He was the Permanent Secretary for Levelling Up at the Cabinet Office from September 2021 to March 2022.

This transcript was edited to make points by both speakers clearer. It has been approved by both.

John Kroencke: To start us off, Tyler Cowen has this phrase: The Great Forgetting.

What he’s getting at when he talks about it is how people, including economists, have forgotten many of the kinds of insights of basic economics and even the major findings of the last 40 or 50 years. This is even more true of people who discuss policy in newspapers and don’t even introduce the basics of the standard Economics 101 response to a policy proposal or the findings of the literature.

Do you agree with that point of view? Has your opinion changed on the importance of basic economics as a rule of thumb?

Andy Haldane: I don’t know about a great forgetting. There’s been, a narrowing, I think, with, maybe to some extent, parts of economics forgetting its roots in moral philosophy – and therefore, an underemphasis of the social part in social science, and insufficient thinking about how other social sciences, psychology, sociology, anthropology, might bear upon their discipline.

I think the profession is now trying to integrate more of those insights into mainstream thinking, and policy. We’re not there yet, but there’s a growing acknowledgement the narrowing went too far, the mathematization of the subject went too far and the distance from real human behavior meant that we had traveled too far. Some of that is a fair critique and has been, at least in part, responded to.

KROENCKE: I would imagine political economy constraints would be relevant as well; that is, how politics is practiced by politicians, and this disconnect between the literature and idealized policy responses, and the real politics involved.

HALDANE: And the role of politics and institutions generally. Institutions have sort of been taken out the equation in terms of how we think about economies, yet we know institutions, both political and non-political, are foundational to economic success.

Elements of other of the social sciences are finding their way back into the economic mainstream. As I say, the kind of engineering approach to economics, perhaps draws excessively on insights from the natural sciences and insufficiently on insights from other social sciences and the arts and humanities.

KROENCKE: One thing that keeps recurring is this kind of discussion about how focused policy is on growth and whether growth per se is the primary goal of economic policy. In recent years, you’ve had this spread of kind of ‘growth, yes, but only of a certain sort’ thinking. So, things like ‘sustainable growth’ or ‘inclusive growth’ or any of these other types of constructs.

In response to this, Paul Johnson of the Institute for Fiscal Studies had this piece, a couple weeks ago, basically saying that people should focus on the core of economic growth and the social benefits that result from growth instead of only focusing on certain types of growth. Did you read that piece or have any thoughts on that?

HALDANE: I didn’t read Paul’s piece, unfortunately, but I can see what he was getting at.

I mean for, for me, growth, whether at the national or individual level, is at best an imperfect proxy of what we should be seeking when it comes to public policy. Longer, larger lives, are for me, what it’s all about. Longer in the sense of remaining healthy, which is foundational, to living a good life, and larger in terms of the opportunity set available to you.

We can’t, and shouldn’t seek to equalize outcomes, but we absolutely should seek, to equalize and open up opportunities to people. We know that is foundational to wellbeing and happiness. We furnish people with the best opportunities to flourish and whether they do so, of course, is in part down to them.

But that for me is the objective of public policy and of a good life which is related to growth but is not umbilically tied to growth. So, this is not a question of what particular flavor of growth: ‘Is it sustainable?’ or ‘Is it inclusive for me?’ For me that’s the wrong question, because while that might make it a less imperfect measure, it misses the bigger point, which is there that it isn’t the right end objective for a good society.

KROENCKE: What would you say about people who push back on the secondary concerns in the UK context, where the level of income per capita is much lower and the economic growth has been much lower than in the US since the financial crisis.

If I were to put this forward it would be something like: we’ve seen a widening gap between Europe and US, and whereas they might say in the US that on the margin growth is less important and it’s all these other things decaying that we should worry about, in the UK, on the other hand, incomes especially outside London are far lower, and growth is still the primary thing. So, while growth may be a proxy for all of those things we care about, it is the feature that is most relevant for improving the lives of Brits and overcoming the state’s fiscal challenges.

HALDANE: The comparison of the US and UK underscores my point: one of the reasons the US has done relatively better in growth terms is because it widens the opportunity set for many people. It provides a longer, stronger ladder than much of Europe.

That has provided dynamism to the US economy and enabled it to grow. But equally, for all the reasons you say, we know that the US has not been a singular success on that front because there are many people for whom the ladder hasn’t become longer and stronger.

That’s the issue of rising inequality or stasis in living standards. Both need to be addressed. The US is an example of the importance of what I say in terms of both in explaining what’s gone right there: strong growth – and what’s gone wrong: too few opportunities for those in the lower half of the distribution.

KROENCKE: In terms of setting out how we think about policy in the abstract, often the focus is either enabling growth, or on correcting market failures. The basic premise is: ‘this is the problem with leaving it to the market and here’s how the state can address it.’

Do you think the market failure aspect has been lost in recent years as myriad policies get proposed to achieve disparate ends, but the theoretical rationale or justification for the policy is hazy?

HALDANE: I don’t know about lost. I think it’s too narrow of a lens through which to view the case for public policy and action. Let me give a couple of examples of that to make it concrete.

Some problems we face are not just existing markets not working as we wish. They’re more a case of markets being missing completely. This isn’t a friction in the market, it’s the absence of a market.

When it comes to, say, tackling environmental and biodiversity challenges. The markets for dealing with that are largely either fledgling or absent. Even if you take something more basic, like the market for education, for many people, especially those on the lowest rungs of the ladder, that I mentioned before, they have been excluded from that market: it’s missing for them individually. I think missing markets are as important as failing ones.

Also, this binary distinction between what is done by the market and by the state, with the state stepping in when the market’s failing, is too simplistic, too binary a view of the way the world works. The greatest leaps forward, for humankind have tended to come from some partnership – not just between the state and the market, but between the state and the market and the key third pillar as Ragu Rajan called it, which is civil society in its many various forms.

The magic happens when the three of those, the public sector, the private sector and what’s sometimes called the third sector, but I wouldn’t call it that because it’s definitely not third on my list, join hands and operate in partnership to get stuff done.

The problem when they don’t is not a market failure because there isn’t a market for that per se. It’s not a market issue; it’s a cooperation and coordination issue between private actors, public actors, and civil society actors. When they’re able to coordinate and play their respective roles, society tends to thrive. When we come to overly rely on one or another of those three, society struggles.

So, to cast this as just ‘more market’ or ‘more state’ risks missing out the third pillar, civil society, which is the civilizing force on the first two. It’s the moral compass of the first two. It’s the societal glue that binds together the first two.

So, I have a different mental model in my head when I think about who the key actors are and the balance between them and the reason why they need to cooperate, and it’s the model I’ve just outlined.

KROENCKE: Do you think the history of civil society in the UK, especially in the 19th century, is just kind of out of mind in the popular imagination?

Obviously, as you know, the UK during that time was one place in which these kinds of strong networks and civil society institutions were acting in many domains, in part because the state wasn’t as large. To some extent in the US, we still find this with faith-based community organizations and other civic non-profits are being quite active in social welfare work.

HALDANE: Civil society, despite being the third pillar or the third sector, is the one that has always been there. Communities are what makes humans, human. They are intrinsic to us as individuals, as social animals, and preceded by many, many hundreds of thousands of years anything that looked at all like the state or government or private enterprise. They are the DNA of societies, despite them operating often very atomistically and quite invisibly, which is why they’re often written out the script a little bit.

What our economies and societies are missing is a stronger third pillar to help coordinate and keep on the path of righteousness, both private sector actors, who do good things but can also do bad ones, and government – which is in the same position.

KROENCKE: Obviously the fiscal environment in the UK but also across the world has deteriorated and there are further stresses forecast in terms of demography and projected demands on government funds. Some people think the third sector can step in more on things that local authorities have done. I saw a recent case discussed by Archie Hall, the writer at The Economist where he was talking about how in Devon or somewhere, a local authority stopped mowing a verge, and people are attempting to take care of it themselves, but they are running into different sorts of, difficulties. For example, they have to get certain certifications and these kinds of things. This is obviously one anecdote but is this kind of thing one reason why we don’t see the third sector stepping in as much? Are there these things that need to be done and people willing to help out but who, if you make it a chore, don’t want to go through that hassle?

HALDANE: I think two things. I think there are some things the state does currently that in the past definitely and arguably, but more questionably, today might be better done at the community or civil society level. That would be, the case for a more selective, degree of state involvement in some activities.

On the flip side there is some risk in saying that: a risk that this becomes a convenient vehicle for governments to step back and hope someone fills the gap they left. That was among the reasons why, when we last had a conversation about this issue in the UK, which is probably the time of the conservative government in 2010, David Cameron, the then Prime Minister’s Big Society idea that foundered on these rocks. It was because on the one hand he was saying we want a bigger role for civil society – that was the big bit – but on the other, he was simultaneously cutting the state back sharply due to austerity. Those two things jarred, and people rightly or wrong put the two together and said: this is an unworthy reason to support civil society. It’s your safety net for austerity.

So, I think there’s a balance between those to be struck.

KROENCKE: One of your themes through the RSA is Robert Putnam’s work on social capital and social connectivity. Within this there is a mix of longstanding trends since the middle of the last century and recent kind of trends in terms of technology and the atomization of social lives.

Where do you see that work going? What tangible things do you hope to learn and what ideas about potential responses do you hope to see in five years?

HALDANE: I think we already know ample about the importance of social connections and social cohesion. We know enough about the foundational role of social capital to know that we’ve got a problem that needs a solution.

The evidence since Bob’s work is compelling, about the foundational importance of connections, cohesion and capital for nurturing individual, community and national flourishing. The key next bit on which we’ve made far less progress is, of course, doing something about it to turn the tide.

I think what we need, and I’ve written a bit about this, is the sort of radical rethink and reformation of social policy on a scale equivalent to what occurred in economic policy during the Great Depression. We need social capital and cohesion running as a golden thread through every aspect of public policy – from how we design our education systems from the earliest of years, right through into universities and colleges so that those aspects are designed in rather than, as now, designed out. Actually, most of our educational infrastructure is socially stratifying rather than socially connecting and cohesive.

You need to do that in the workplace and in the design of our cities and transport systems. We need to do it in how we think about homeland security in its many various forms. We need to do it in how we think about our communications, both mainstream and social media. There actually are very few aspects of public policy, which is essentially about how people get together, that wouldn’t benefit from this lens.

When it comes to design, the key is to design it into systems from the get-go rather than have it designed out, as is too often the case now. That’s a radical program of reform, and one that is needed for our times. Unless and until you tackle the social capital crisis, you are building an economy on shifting and unstable societal sands, and this is something that our politics is telling us.

KROENCKE: When you say design, I would imagine what you have in mind is design that also enables nested communities to control their own things with the principle of subsidiarity as part of that design process, rather than everything being done by the central state.

HALDANE: This can only be done at the level of local or hyper-local communities. The patterns of cohesion and connections are themselves hyper-local. You have communities often, typically even, sitting next to each other, but not talking to each other.

There’s no way national government could bring the precision surgery necessary to fuse those communities together. It needs local leaders and by local leaders, I don’t necessarily mean local government. This may be a role better played by local civil society organizations.

One of the great bonding agents, and one of the great neglected areas of public policy are institutions that serve as bonding agents for communities You mentioned faith-based groups, which are very important in the States. Here, sports, leisure and cultural activities play a crucial role in bringing people together. We think of those as ‘nice-to-haves’, but they’re actually foundational to a good life because they’re foundational to social connections and a thriving economy.

KROENCKE: One thing I find interesting in the UK is that local authorities’ fiscal attention is increasingly only focused on statutory duties imposed by the central government. So, you have council taxes going up, but by the maximum rate they’re allowed to go up to, because of social care and other duties, which there’s no real public finance reason to have dealt with by the local authority.

It seems like this problem hasn’t been taken care of because the general governance at the local level can’t evolve to focus on things best done at the local level. Do you think there’s any way out of this? First, do you agree with that analysis? Second, is there any way out of this situation such that local governance can be improved, and local communities can flourish?

HALDANE: Yes, it’s the short answer to your questions, John. it’s understandable why local authorities were given a relatively narrow set of statutory duties that they had to fulfil.

But, one, that is too narrow a set of objectives to make for good communities; and two, it inhibits the flexibility of local leaders to make different choices. I mentioned those bits of social infrastructure that are so important to communities. One consequence of them not being in such objectives is that they’ve taken the hit as local authority budgets have tightened up. People have prioritized by statute, social care and bin collection – and the library’s gone, the museum’s gone, green space has gone in a way that has taken the legs out of many communities in a very fundamental way. That was a big mistake.

How do you remedy that? One way is to cast statutory objectives in a broader way. We’ve suggested that local leaders be given the flexibility including financial flexibility to make the choices they think are most appropriate to their area, which is not currently done.

It has been mooted with single financial settlements for mayoral combined authorities, and that’s directionally right. It remains to be seen whether that will give local leaders the flexibility they need to make the choices they think local citizens crave. We need, a real letting go, of both the purse strings and apron strings by central government, allowing local government to do its job and make choices in the interests of local people.

KROENCKE: You had a recent piece looking at Treasury Brain. As an American, I’m used to a system where a percentage of the property value is taxed every year, and that money often goes mostly to the local authorities. They use this to provide various services like schools and police. In the UK, various aspects of that are just completely wrong, and have been for a long time. Instead, there is a relatively small council tax to pay for services and a transaction tax on property sales (stamp duty).

And if we look at stamp duty, it’s an inefficient way to raise revenue. It stops productive economic decisions from being made. But my understanding is that the Treasury is one of the biggest proponents of stamp duty in the sense that it is a reliable source of income and therefore it’s difficult to get rid of despite harming economic efficiency.

Do you think there’s hope of reforming the tax system to enable these types of things to happen?

HALDANE: I hope so. I think it’s going be difficult to reconcile the fiscal arithmetic without coming back to the question of whether our tax system is fit for purpose. Are we taxing too much? Too little? Are we taxing appropriately the different sources of income? Do those tax powers reside at the right level?

My strongly held view is that some tax powers ought to reside at the local level, as would be common, well, in pretty much every country on the planet, to be honest. Very few of them currently do in the UK and that’s part of the devolution agenda that’s hardly got any mileage at all, but ought to have – not least for reasons of accountability. If local leaders have extra spending powers, they should be held to account, by having to raise the money themselves for the local activities they take on and to justify to the local electorate why they’re raising taxes to justify their spending.

That’s a good incentive to keep local leaders honest. There are areas of taxation where the system is crazy. Property is the craziest, where we have a tax on transactions, which most people would argue it is a very efficient way of earning money if you’re the treasury but has a chilling effect on the housing market.

There’s a real inefficiency, which is unhelpful, because moving jobs and houses often go together. So, it is mostly a tax on housing transactions, but actually it is a practice that ends up translating into a tax on job moves. A tax on job moves is a tax on pay because the way you boost your pay is by moving job. And then of course there’s council tax – and that is one of the most egregiously regressive taxes. It’s impossible to justify actually: no one can defend council taxes as currently configured. It’s totally mad – and not just the failure to update to account for price inflation over the last20 years or so, but the very principle behind it is all at sea. So, I think that’s known and that’s been known a long time. Anyone who has thought about it for more than five minutes would tell you that something based on land values would make much more sense, but what is needed is the political will to make that happen, given that it would involve half the population being worse off.

KROENCKE: We’re just in a bad equilibrium that we’ve trapped ourselves into.

HALDANE: A bad equilibrium and the longer we leave it, the harder it is to escape.

KROENCKE: And on the trap for high marginal tax rates facing people at around £100,000, it’s only getting worse now that thresholds have been frozen, and more people are falling into this category. So, a lot of fiscal traps with dynamic consequences are just getting worse, because of the fiscal problems the country is facing.

Just before we end, I don’t want to miss asking you about leveling up and regional inequality – if you could first set out why you think it’s important and then go into the international comparisons and lessons we can learn from other, countries.

HALDANE: Yes, it’s important. The case is partly economic, because there’s lots of untapped potential opportunity in places. This is untapped opportunity that would make for longer, larger lives, for many more people. There’s a deadweight economic cost from not doing that.

The case is equally well made on social justice grounds. It is unjust to be not offering people in those places, who but for their geography would have, the opportunity to rise and shine. So, for me, this is partly an economic case, but as importantly, a moral one, a social justice one about what makes a good society.

Equal equality of opportunity for everyone plainly isn’t the case right now. Many people are held back by their history. In other words, they’re born into a poor family. Many people are held back by their geography or where they’re born.

And of course, many are doubly damned because they’re a poor person growing up in a poor community and therefore, they’ve faced the double barrier of both history and geography. We need to do a better job of lowering those boundaries in the UK. We are holding back our potential of individuals, communities, and the country as a whole.

The UK disparities are larger than elsewhere, which makes the case even stronger. The barriers are even higher here, so the public policy case for lowering them is even greater.

Ultimately this is down to the holy trinity of people, powers and monies. Local areas need more of all three: they need the powers to be marked with their own destiny; they need more money to make good use of those powers; and they need local leaders in government, civil society and the private sector who can use those powers and monies to drive the opportunity.

That is the recipe from elsewhere. It’s a recipe book. We haven’t fully followed in the UK yet.

KROENCKE: I have two questions on inflation given your long role at the Bank of England. Firstly, why did central banks miss the potential for inflation? Secondly, why did markets miss the potential for inflation?

HALDANE: It’s the same reason for both. I think it does boil down to where you started, which is the Great Forgetting.

The financial crisis 15 years ago happened for a bunch of reasons, but one important reason was that the last person who’d experienced a global financial crisis had left the room. I think the same is true of the inflation we’ve had recently; the last person who’d experienced inflation had left the room.

That was a Great Forgetting and a Great Myopia. We’re prisoners of our past experience. That was among the reasons we missed it this time, both in the private sector and the central bank community.

KROENCKE: Do you think markets are not looking seriously enough at the threat to central bank independence in the US?

Trump at various points says things, then rolls them back. It seems some of that risk has gone away, but can we be certain?

HALDANE: My general sense is that central banks got it wrong, on inflation and that that puts them in a more perilous position than they have been for a couple of decades when it comes to independence.

I do think that puts them in jeopardy to a degree. The discipline effect of markets recently demonstrated in the US will give politicians cause for pause. It will take more than one inflation miss to turn the tide in independence in a significant way.

KROENCKE: Someone like Maurice Glasman, who also spoke at the event with Brian Griffiths where you spoke, or other figures, might view this as markets acting anti-democratically and against the people because of this restraining effect on a democratically elected person. Do you think there’s another side to that argument, perhaps in terms of this being a case of markets stopping someone from doing something that’s going cause economic harm?

HALDANE: Well, Maurice is a great friend and ally, but it is certainly a questionable proposition about whether any one politician at any time could ever be said to be acting according to the democratic will of the people. That is the sort of thing that autocrats say all the time.

I think we’d be careful about using that kind of argument as a justification for, any act and financial markets are a democracy too. Just a different cohort. And so obviously are those at the ballot box. They’re equally important in keeping us on the right track.

It has been reported that Ribbon AI, a Canadian company, is offering employers a new form of screening interview conducted by artificial intelligence. With a view to helping organisations hire staff more quickly and job-seekers find work sooner by cutting out ‘dead time’ in the recruitment process, early stage job interviews are conducted in a fashion similar to a remote interview, with applicants responding to questions and prompts from a natural sounding voice, generated by AI.

The idea is that the AI interview saves time for job-seekers, who get to interview almost immediately rather than waiting for two or three weeks until a member of the HR department can see them. Ribbon does not make decisions about candidates; rather, it provides companies with applicants’ responses to questions, offering transcripts, summaries, analyses and scoring of candidates’ responses, which the company can then use to inform its decisions according to internal criteria and requirements. As such, it is intended that companies should gather information about candidates and assess their suitability for roles more efficiently than by way of an early-stage screening interview.

It is worth pausing to ask what candidates are being expected to do here.

It is not uncommon for companies to ask applicants to complete psychometric tests prior to offering an interview and with increasing frequency, candidates will also be provided with set questions and instructed to submit answers recorded using a web-cam. Anyone Who has been through such a process might have experienced certain misgivings. The rationale behind including tests is intelligible (though it is not always clear whether they really determine which candidates possess the skills requisite for the role on offer) but recording answers can feel artificial. We might wonder what is to be gained by this approach, and why the hiring company is unwilling to talk to candidates in person at this stage, particularly if it is serious about ultimately hiring and investing in a member of staff. In any event, if the recorded answers are assessed by a member of HR staff or a hiring manager, it is not clear how far such an approach is any more efficient than a short, standard-format interview. Perhaps the most sympathetic view is to see such an approach as being akin to recording a spoken assessment as part of a remote learning course, perhaps in modern languages. Strange as it feels to be speaking (in)to a machine, candidates assume that the recording will at least be properly assessed by a human being at some stage.

In this instance, however, it seems that candidates are being expected to speak to and interact with a machine as though that machine were the human interviewer. An applicant is in effect asked to hold a conversation with an interlocutor that has no consciousness, is unaware of the interviewee’s existence and understands neither the candidate’s answers nor even its own questions. In such a situation, there can be said to be no conversation at all and therefore, arguably no interview. This is a peculiar arrangement, whereby an applicant is expected to behave as though a non-conscious object is interviewing her.

Moreover, her responses are not necessarily going to be sent to a human assessor for consideration at all. Rather, a decision might very well be made based on an analysis and data produced by the AI based on her responses. These analyses may be less biased and more uniform than would be possible for human interviewers, but the applicant has been ‘interviewed’ and ‘assessed’ by a machine. She might be rejected without any human consideration of the actual performance itself at all. Instead, the candidacy depends on a view taken of a computer generated assessment of that performance.

What does such an approach suggest about a company’s attitude to applicants, when it chooses to have them prove themselves before a machine before granting any meaningful human interaction?

Andrei Rogobete has written about the need for a human-centric AI, stating that AI ‘ought to be embraced in a prudent manner that directs its contributions towards human thriving’. In arguing for a use of AI that benefits humanity first and foremost and does not deify machines, he quotes Pope John-Paul II’s call for humanity to ‘use science and technology in a full and constructive way, while recognizing that the findings of science always have to be evaluated in the light of the centrality of the human person (and) of the common good’.

If we are to make responsible use of artificial intelligence for the good of humanity, the technology ought to be restricted to those tasks which any given form of AI performs well, so that it brings clear, tangible benefits to all relevant parties. Crucially, the dignity of the human beings that this form of technology is to serve should always be our foremost consideration. It is pertinent to ask, therefore, whether reducing interviews – for which candidates will often prepare carefully and about which they are ordinarily nervous – to a confected and solipsistic ‘conversation’ with a non-conscious AI model rather than meaningful engagement with other human beings is indicative of such an approach. Is it consistent with human dignity to base decisions about an individual’s potential livelihood not on a meaningful conversation with that person – and perhaps not even directly on her responses themselves – but on the reduction of her performance to a collection of data and analytics produced by artificial intelligence – artificial intelligence which has not seen or heard, let alone engaged with or understood the person in question?

Why does Scotland use more water than the rest of the UK?, BBC

(Open Access)

As one of the wettest parts of the UK, it is counter-intuitive to think that Scotland faces a water shortage, but only 1% of rainfall is captured in reservoirs, while the way in which Scots pay for their water may be responsible for a higher rate of use. With relatively few households in Scotland using a water meter, charges for water are linked to a home’s council tax band. Rather than pay for water consumed, therefore, users face a flat charge, yet evidence suggests that those on water meters tend to consume less water. Along with industrial use and a perception of abundance, the lack of water meters may play some role in Scotland’s relative over-consumption of water:

AI alone cannot solve the productivity puzzle, FT

If human ingenuity thrives where precedent is thin, and if large language models gravitate towards statistical consensus, perhaps artificial intelligence is unlikely to yield the results anticipated by so many in areas of productivity and research. It is possible that artificial intelligence admits of gains in terms of efficiency but offers little in terms of creativity, for which human collaboration and ingenuity remain essential. Perhaps real gains require not just new digital tools, but genuine innovation to accompany them:

Entry-level jobs plunge by a third since launch of ChatGPT, The Times

The number of new vacancies for entry-level jobs has fallen by almost a third since the launch of the AI tool ChatGPT in November 2022, and the chief executive of Anthropic, an AI start-up company, has suggested that unemployment could rise by between 10 and 20 per cent, as AI eliminates half of entry-level jobs within five years. Many businesses have indicated their intention of using AI to reduce their workforces, particularly when faced with higher costs in the form of rising tax obligations and a higher minimum wage:

Council faces £100k tax bill after ban on second home owners backfires, The Telegraph

West Norfolk Council is considering lifting its double-taxation policy on second home owners in relation to one development, after a newly built block of flats attracted no buyers for any of the 32 residences it contains. The result is that the council risks becoming liable for a tax bill of around £100,000 as of February next year:

Remittance crackdown is a tax on the poor, FT

With the U.S. President keen to tax migrant remittances – presumably as part of his efforts to address illegal immigration by making it necessary for those sending money home to prove that they are U.S. citizens in order to avoid the levy – some have suggested that this amounts to a tax on the poor and hard-working, which will push remittances into crypto and underground networks while ultimately depriving poorer countries of an otherwise resilient form of finance:

Wealth tax will penalise savers, Labour warned, The Telegraph

MPs and unions have followed former Labour leader Neil Kinnock in calling for a wealth tax in the UK, the proposed measure being a tax of 2 per cent on assets over £10 million. A poll suggests that this would find widespread support with the public but the Institute for Fiscal Studies has warned that repeatedly taxing the same wealth would penalise savers and discourage investment while driving the wealthy to emigrate, adding that several countries that had introduced wealth taxes had ultimately abandoned them:

California’s carbon market reaches an inflection point, The Economist

There is no federal carbon trading programme in the United States and there are doubts about whether California’s cap-and-trade system will continue. This, together with falling carbon prices within California, has created uncertainly beyond the state, as other states on the west coast consider whether to link their own programmes to that of California:

Another fake Net Zero market that nobody wanted is set to collapse, The Telegraph

With the bioethanol producer Vivergo at risk of having to cease operations owing to competition from the United States, are we seeing a case of a company ‘exiting a market’ that exists not as a result of any genuine consumer demand, but purely to meet the requirements of government policy? As bioethanol is produced largely for use in ‘green fuel’, it is arguable that no real market has ever existed for it – only one created by government to meet environmental targets. Now that a trade deal has been agreed with the U.S., it is likely that domestic bioethanol will be displaced by imports, but the transportation of the imported bioethanol is likely to negate any carbon emissions saved by its use in the first place:

Meta’s AI climate tool raised false hope of CO₂ removal, scientists say, FT

Using an artificial intelligence tool, Meta has claimed to have assisted scientists working in the area of climate mitigation by publishing a data-set that would help to identify materials that can remove carbon dioxide from the air – Direct Air Capture (DAC) being a field in which tech companies have invested in the pursuit of means to reduce their own carbon footprints. However, none of the materials identified by Meta as being able to bind carbon dioxide strongly had that attribute and some did not even exist, leading to accusations by researchers that the AI tool had been trained using faulty data:

Following changes to the UK tax system – specifically the abolition of non-domicile tax regime – there are reports that the mega-rich are leaving the country in droves. It is difficult to assess the actual impact and estimates of the numbers of likely departures vary. Likewise, opinion differs on what the tax changes are likely to raise, with some predicting a figure of over £33 billion over five years, while others suggest negligible gains. There is now talk in political circles of a simple flat tax for ‘non-doms’, similar to the kind that is said to be drawing the super-wealthy from London to Italy:

See a physio, quit the fizzy drinks: employers intervene to stem ill-health exodus, FT

As the bill for sickness and disability benefits in the UK appears likely to rise and surveys suggest that employees consider themselves to suffer from ill-health in significant numbers, might occupational health, led by employers, be the answer to keeping people in work or helping those currently unable to work to return? Interventions of various kinds led by employers – whether referrals, employee assistance programmes, advice or health-checks – may reduce absence through sickness and staff turnover, but there remain questions of cost and workplace culture to consider:

Rachel Reeves will need to face up to fantasists on both sides, The Times

Politicians on both sides of the divide seem unwilling to offer serious solutions to the country’s financial position, and appear to be unable to contemplate the very stark choices made necessary by the fact that public borrowing, debt and costs are persistently high. By way of example, responses to the need for welfare reform have been naïve, with proposed solutions including modest tax increases, tax cuts, changes to the Chancellor’s fiscal rules and welfare reform that tackles misuse of the system by those who can work but won’t – a very small proportion of welfare spending. Stable public finances need more serious approaches and a sustained strategy:

30 June 2025

We have compiled some news, comment pieces and announcements that we hope our readers will find interesting. In this instalment, there are stories relating to artificial intelligence, pensions and savings, state intervention in markets, and housing:

CEME’s latest publication, Inflation is About More Than Money, by Brian Griffiths, is on Martin Wolf’s list of ‘Best Summer Books of 2025: Economics’ at The Financial Times:

CEME’s latest publication, Inflation is About More Than Money, by Brian Griffiths, is on Martin Wolf’s list of ‘Best Summer Books of 2025: Economics’ at The Financial Times:

Make America French Again, The Economist

The current United States administration, with its apparent preference for tariffs, state ownership and price controls, appears to be showing ‘dirigiste’ tendencies traditionally associated with the French government. While some businesses that stand to benefit are in favour of this, others are less enthusiastic. In the period when France and the U.S. were rather more similar than they are at present in terms of government involvement in markets, the performance of companies in both countries was somewhat weaker than it has been in America since President Reagan’s free-market reforms

Britain’s AI-care revolution isn’t flashy—but it is the future, The Economist

The care sector appears to be one area in which artificial intelligence can offer concrete benefits, with some providers using the technology to arrange the schedules of care staff, while others employ it to predict and therefore reduce falls among clients, or install devices similar to Amazon’s ‘Alexa’ so that residents of care facilities can request help, ask for drinks or make emergency calls. Many are keen to stress that there are limits to what AI can achieve and that in a fundamentally human sector, people should not be too heavily bound by technology and metrics and should take care not to follow the path of surveillance and control that such technology so easily affords: in short, AI exists to support rather than replace staff

Does anyone really want AI civil servants?, The Spectator

Given that artificial intelligence is known to ‘hallucinate’ and that it is as yet unclear how to address this problem, and given that AI models are trained on existing data, which raises questions about copyright, plagiarism and legal risk, should we be concerned about plans to put AI at the heart of the civil service, beginning with the implementation of an AI tool across the civil service? Will the risks and errors ultimately negate any efficiency savings? Perhaps the right approach is one of extreme caution

Disrupted or displaced? How AI is shaking up jobs, Financial Times

Many large companies are investing heavily in AI to boost productivity, leading to concerns over worker displacement. The trends differ according to the nature of the work, with some sectors seeing much higher rates of redundancy as a result of AI than others, though most people anticipate a radical restructuring of the employment landscape and the nature of work as automation becomes more prevalent. There are questions about how long this trend will last, but it is perhaps significant that, according to a report by PwC, revenue growth per employee is currently three times higher in the industries considered ‘most exposed’ to AI than in those considered ‘least exposed’. Does this mean that automation will replace more workers, or that AI renders individual members of staff more valuable?

Uber to bring self-driving cars on to Britain’s streets next year, The Telegraph

There are plans for the ride-hailing company Uber, in partnership with the Cambridge-based software company Wayve, to pilot autonomous vehicles on London’s roads next year. The tests will allow cars to operate without a human safety driver present at the wheel. Self-driving cars have been on streets in the United States for some years but have been accused of causing traffic jams and accidents. Following an accident in 2023 involving one of its Cruise taxis which caused serious injuries to a pedestrian, General Motors abandoned its autonomous vehicle programme. An earlier accident in which a pedestrian was killed involved an Uber vehicle, though Uber was found not to be criminally liable and the human safety driver entered a guilty plea of endangerment

British pension policy is finally stepping in the right direction, Financial Times

The government’s proposed amendments to pensions appear to aim at consolidation and economies of scale, the idea being that the outcome will be a smaller number of larger schemes making more efficient use of capital through a wider range of investments. This article suggests that the aims of consolidation, productive investment and higher savings are laudable first steps in the right direction for addressing the failings of a fragmented pensions landscape that does not necessarily make the economy more productive

Rachel Reeves is about to do more damage to pensions than Gordon Brown, The Telegraph

An alternative view is that the reforms to pensions will reduce savings by removing tax incentives to use salary sacrifice schemes and by rendering private pensions liable to inheritance tax, and will also affect returns by allowing the state to assert control over where funds are invested. Thus, pensioners will be poorer and returns lower, while British equities will become less appealing because their ability to attract investment will depend less on performance in a competitive market than on arbitrary factors such as geographical location or state preference

Britain is saving but it’s not investing in the economy, The Times

Households in the UK are saving more of their disposable income but have a tendency to hold it in cash savings rather than invest in financial markets. Such behaviour is based on expectations about the likely value of property and the future generosity of state pensions, as well as fears about losing money through more ‘risky’ investments. It is possible, however, that people’s savings would work harder for them if invested earlier and in stocks, while also providing money which businesses could borrow in order to grow

Labour ‘will fall well short of target of 1.5m new homes’, The Times

With only 39,170 new homes receiving approval in England in the first three months of this year, together with reduced demand from first-time buyers and housing associations, it is expected that only around half of the 1.5 million new homes pledged by the government by 2029 will actually be built. Some have suggested that some kind of ‘demand support’ such as a ‘help to buy’ scheme would be required in order for the target to be met

My colleague, Dr. Dave Hebert, wrote a nice overview of different types of inflation and how they can affect people. He pointed out that the rate of inflation can be high or low as well as anticipated or unanticipated. He also explained how inflation is fundamentally a monetary phenomenon: too much money chasing too few goods.

In this piece, I’ll explain some of the mechanics behind how central banks can stoke inflation unintentionally. I’ll also raise several phenomena that ordinary citizens can keep an eye on to determine whether their central bank is acting responsibly or recklessly.

Let’s start at the most basic level. How do central banks increase or decrease the money supply? They primarily do so by purchasing government debt (bonds) with newly created money – really just an electronic entry on their balance sheet – or by selling bonds into the market and thereby ‘extinguishing’ the money they receive from the sale, in effect pulling money out of circulation.

Before the 2008 Global Financial Crisis (GFC), central banks like the Federal Reserve could not manage the money supply by simply buying or selling as many bonds as they liked. Significant buying or selling of bonds will affect the price of bonds, and correspondingly the market interest rate on those instruments.

When a central bank sells bonds to reduce the money supply, they drive down the price of those bonds, which increases the rate of return, or the interest rate, on those bonds. Conversely, when a central bank goes on a bond-buying spree, they drive up the price of the bonds, reducing their rate of return or interest rate.1

This partially explains why people pay so much attention to central bank interest rate targets. Changes in an interest rate target are a proxy for what is happening to the money supply. And as Hebert notes, what happens to the money supply is a proxy for what will happen to the price level. The connections between interest rate movements, money supply changes, and price levels are not tight or precise in the short-run, but they do have strong correlation over time.

A regime of low interest rates (or more precisely, of falling interest rates) suggests an expansion of the money supply and higher future rates of inflation. And a regime of rising interest rates suggests a reduction or ‘tightening’ of the money supply and lower future rates of inflation. Two bouts of inflation in the United States demonstrate how interest rate targeting monetary policy can be used. In 1980, the U. S. inflation rate rose to over 14%. In 2022, it rose to over 8%.

In 1979, President Jimmy Carter appointed Paul Volcker chair of the Federal Reserve to combat inflation. Under Volcker’s leadership, the Fed stopped buying government bonds which had been keeping short-term interest rates artificially low. In other words, the Volcker Fed allowed interest rates to rise rapidly – peaking at about 22% in December 1980. Although painful at the time, by 1983 the U. S. inflation rate was back below 3%.

Similarly, the Federal Reserve raised interest rates from less than half a percent to over five percent between 2022 and 2024 to bring down the U. S. inflation rate from over 8% in June 2022 to under 3% in May 2025. The interest rate hikes in the early 1980s and the early 2020s were accompanied by the Fed selling more bonds (or letting more bonds mature) than it purchased.

It’s important to note that post GFC, most central banks changed their operating framework to decouple interest rate decisions from balance sheet decisions (deciding whether to buy or sell securities). Though they would still tend to move in the same direction (raising rates & reducing the balance sheet or lowering rates & increasing the balance sheet), these two things no longer have to move together. That decoupling was by design and made it easier for central banks to change their target interest rate.

Central bankers, in the wake of the GFC and anemic economic recovery, wanted more tools to stimulate the economy. They had already pushed short-term rates to zero or slightly below zero in the European Union, but they wanted to do more. Decoupling bond purchases from interest rate targeting allowed central banks to inject huge amounts of money into markets through large-scale purchases of assets – called Quantitative Easing. For example, the Fed bought nearly five trillion dollars of securities between March of 2020 and March of 2022 – which clearly played a role in the worst bout of inflation in the U. S. in four decades.

Central banks have kept interest rates artificially low over the past couple decades – meaning interest rates would be higher given existing market conditions if central banks were not actively intervening in financial markets. An important effect of these artificially low interest rates, and large-scale asset purchases, are that national governments have been able to borrow at remarkably low interest rates. And, as a result, most national debts have ballooned relative to the size of their economies. Between 2005 and 2025, U.S. national debt rose from 63% to about 120% of GDP, U.K. national debt rose from 45% to about 104% of GDP, Japan’s national debt rose from 175% to about 235% of GDP (Figures 1 and 2).

Inflation is a simple phenomenon with complex causes. Central banks, however, play a key role because they manage currencies and can use their ability to create money ex nihilo to intervene in financial markets and distort the cost of borrowing. We can see a mutually reinforcing cycle of central banks buying large quantities of government debt, which lowers the cost of borrowing and encourages governments to issue even more debt, which central banks then buy with new money. This cycle is fundamentally inflationary.

Citizens concerned about inflation should follow three issues with respect to their central bank. The headline inflation rate has primacy of place. But citizens should also follow interest rate target changes to understand which way the central bank is moving, towards higher or towards lower inflation. Finally, concerned citizens should keep an eye on the size of their central bank’s balance sheet and encourage the bank to reduce its footprint in financial markets.

1 The majority of government bonds are ‘Zero-Coupon Bonds’, which means they will pay a set amount – the face or par value – of the bond in the future. For example, a government may issue a bond that will pay the bearer $100 in five years. You will gain no interest return if you pay $100 for that bond today. If you only pay $90, though, you will earn $10 of interest when the bond matures in five years. If the price of the bond drops and you only have to pay $80 for it, you will gain $20 in interest. However, if the bond price rises to $95, you will only receive $5 of interest when it matures. So the price of the bond and the amount you earn in interest, the effective interest rate, move in opposite directions.

Paul Mueller is a Senior Research Fellow at the American Institute for Economic Research. Dr. Mueller also owns and runs a bed and breakfast in the mountains of Colorado with his wife and five children.

Paul Mueller is a Senior Research Fellow at the American Institute for Economic Research. Dr. Mueller also owns and runs a bed and breakfast in the mountains of Colorado with his wife and five children.

Subscribe to the CEME Substack

Inflation is a topic that plenty of pundits and talking heads have brought up on the news. For the non-economists, it might seem as if they do so ad nauseum. Despite its frequent coverage, however, few people understand why the U.K., like much of the rest of the world, generally accepts the idea that targeting two percent inflation is ‘good’ while inflation of any other number is ‘bad.’

Here, I want to provide some surface-level thoughts on these questions. While this will certainly not delve into the topic at the depth necessary to complete a graduate course in monetary theory, it should provide sufficient detail to enable meaningful and productive dialogues, which is ultimately what the world needs.

Milton Friedman once remarked that ‘inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon.’ What he meant by this is that inflation is caused when the amount (or quantity) of money increases relative to the amount of goods and services produced in an economy. In a dynamic economy characterized by economic growth and progress, inflation would occur when a central bank increases the money supply faster than the economy grows.

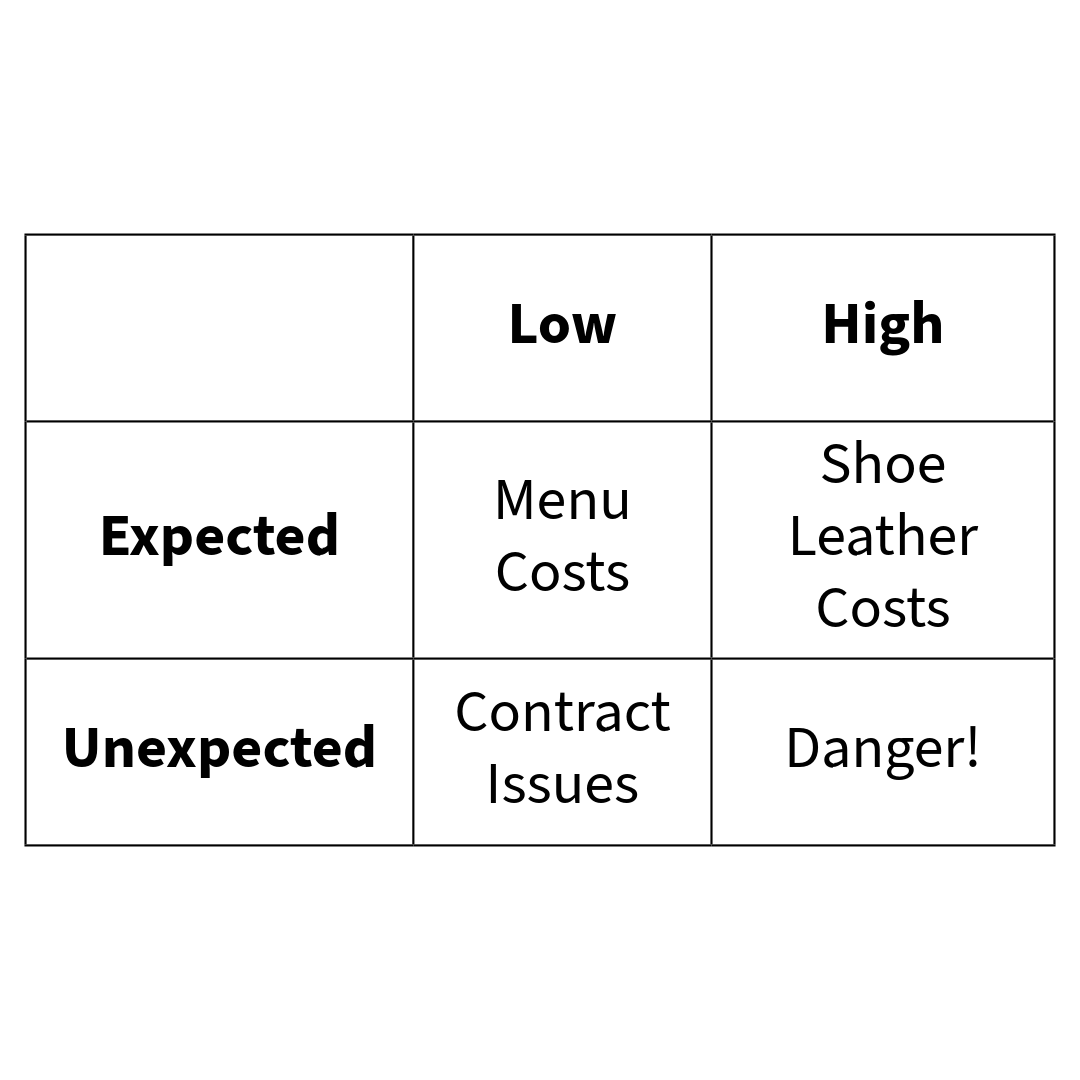

To address this question, it’s useful to think about inflation along two dimensions: 1) whether the inflation is low or high and 2) whether the inflation is expected or unexpected. I will not attempt to define ‘low’ or ‘high’ in this essay. Instead, I will simply defer to the reader’s judgement of the inflation rate in light of the following.

Expected and unexpected, however, are self-explanatory but carry with them implications that may not be intuitive. If inflation is fully expected, e.g. if the people expect 2% inflation over the coming year and the inflation rate is 2%, then the inflation will be relatively benign as buyers and sellers writing contracts lasting the duration of the year will build the anticipated 2% inflation rate into their negotiations. However, if people expect 2% inflation and the inflation rate differs from this, then there will be some unexpected inflation.

Thinking along these two dimensions allows us to put these into a matrix, which I explain in further below:

In situations where inflation is both low and expected, the problems are relatively benign. One that was an issue in yester-year is referred to as ‘menu costs.’ Here, the changing prices will cause stores (particularly restaurants) to have to change their stated prices. In a world of physical, paper menus and magazines, this means reprinting them and sending new magazines out to customers, which is costly.

This was exemplified in the U.S. with Subway restaurants, which had a promotion called the ‘Five Dollar Footlong’ where any full sized sandwich with standard toppings (i.e. no ‘extra meat/cheese’) cost $5. The jingle from the commercial was so catchy that Subway had a very difficult time keeping up with customers’ expectations as inflation increased the nominal cost of producing a sandwich. To keep up with it, Subway initially reduced the amount of meat/cheese included per sandwich. Then they excluded certain sandwiches from the promotion. Eventually, they even shortened the sandwich. However, there is only so much ‘shrinkflation’ that they could get away with and they were forced, eventually, to abandon the promotion altogether in 2014, much to the ire of devoted customers.

In situations like this, we see all sorts of seemingly-wild behavior that is rendered intelligible through understanding economics. One such behavior has to do with employees. When nominal prices are rising quickly (even throughout the course of the day!), employees will demand to be paid more frequently so that they can spend their earnings before the value of the money drops even further. Because of this, they will take frequent trips to the bank or to stores, thus wearing down their shoes more quickly, earning the moniker, ‘shoe leather costs.’

Unexpected inflation, even if it is low, can cause problems for long-term contracts. For example, suppose that everyone expects 2% inflation but the inflation rate is actually 3%. In this instance, money in the future is worth less than even the people entering the contract expected. This will mean that sellers will be harmed and buyers will be advantaged as they are paying with money that is worth even less than they had anticipated.

If the inflation rate were actually 1% instead, then money will be worth more in the future than both parties anticipated. This means that buyers will be harmed as they are giving up something more valuable than they expected and sellers will be advantaged as they are getting something more valuable.

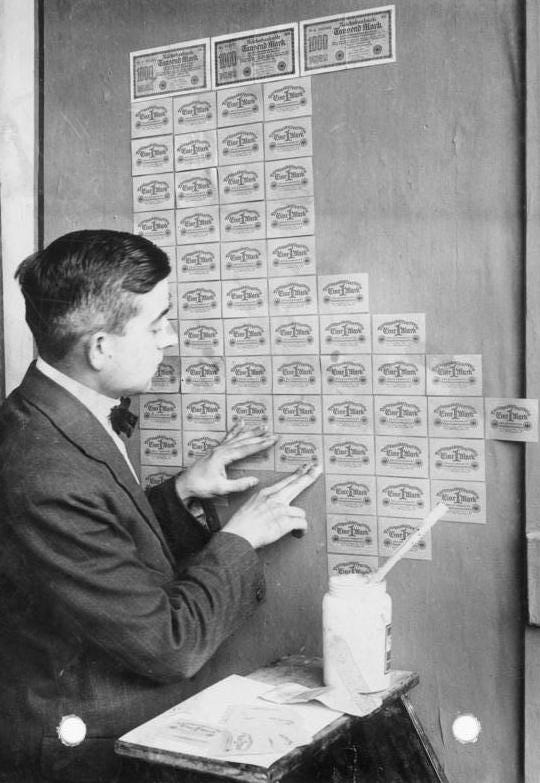

Often, this is a sign of a country’s collapse, as they find themselves having to inflate the money supply so quickly as to render money effectively meaningless. Why they get trapped in a situation like this is a topic for another day, but the short version of it is that the central bank/government faces two options, neither of which is good: hyper-inflate the money supply and delay their economy’s ultimate collapse in the hopes that things will get better or cease inflating the money supply and cause its immediate collapse. Neither of these options are ‘good’ and often portend disaster.

One might ask a simple question: why have an inflation target to begin with? For starters, having a target gives central banks a sort of benchmark to judge whether they have gone ‘too far’ or ‘not far enough’ in their operations. But why have a target that is different from zero? After all, if inflation only imposes costs, then it would seem that targeting zero inflation would be prudent.

First, there was a little problem in the U.S. in 1929 called ‘the Great Depression.’ While there is much debate as to what caused it, one factor that is generally accepted is that banks had loaned out too much money too quickly over the course of the 1920s. As a result, their cash balances were severely depleted. Without sufficient cash on hand, banks could not meet the withdrawal requests of their patrons. One way to make sure that banks always have enough money on hand is for central banks to make sure that they always have a little bit too much money on hand, but this leads to inflation.

Second, the very nature of a ‘target’ is that it can be and often is missed. By setting a target above zero-percent, central banks ensure that their errors will not result in negative inflation or ‘deflation.’

With low, expected, and consistent inflation, however, many of the problems above disappear. Indeed, even the ‘menu costs’ problem has all but disappeared thanks to the rise of online shopping and the fall in television displays as menus in restaurants, which can be updated instantly.

In fact, there may even be some benefits to low inflation. John Maynard Keynes, for all his problems, did recognize one fact that seems particularly important: some prices tend to be ‘sticky’ or ‘slow to adjust,’ especially in the downward direction. One important price that fits this description would be wages. People just do not like to see their salaries decrease. In fact, people often feel better if they get a raise in their nominal paychecks even if their new paycheck is able to purchase less (due to inflation) than their previous paycheck.

For this reason, having consistent inflation can be helpful for employers, who can lower someone’s real wages without reducing their nominal wages. While this is certainly lamentable and we do not wish to see it happen to anyone, it does happen in e.g. industries that are in decline.

Incidentally, this is also where the 2% target rate comes from. 2% is most certainly ‘low’ and if it is expected, well, then it will be relatively benign on the economy as a whole. There is nothing magical about the number two here. It’s not so high that it would cause a truly noticeable increase in nominal prices year-over-year but it is high enough that to allow for real price decreases despite increasing nominal prices. In the end, low, expected, and consistent inflation may impose some costs on society but it may also provide some benefits. As for whether a central bank can deliver low, expected, and consistent inflation is a question that is up for debate.

David Hebert is a Senior Research Fellow at the American Institute for Economic Research. His work can be found at www.davidjhebert.com.

Follow him on X: Dave_Hebert

Image: Germany, 1923: During hyperinflation, banknotes had lost so much value that they were used as wallpaper, being much cheaper than actual wallpaper.

Bundesarchiv, Bild 102-00104 / Pahl, Georg / CC-BY-SA 3.0, reproduced from Wikimedia commons under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Germany licence.

Inflation Is About More Than Money by our Founding Chairman and Senior Research Fellow Brian Griffiths has been named as a Best Book of Summer 2025 by the Financial Times in the economics category compiled by Martin Wolf.

The full list is available here.

Full details about the book are available here.

Perspectives on contemporary issues

There are growing concerns that capitalism and democracy are in crisis. Despite the success of free markets in creating global prosperity over two centuries, the recent slowdown in growth in Western economies, the persistence of inflation, increasing economic inequality, financial instability and the explosion in debt have called into question the value of market capitalism. Moreover, trust has been eroded in liberal democracies because of dysfunctional governments, a perceived lack of commitment to truth and political leaders playing the game to the edge of legality. Added to these concerns are the growth of a post-modernist culture with steadily increasing social fragmentation, divisiveness and the lack of a unifying and accepted source of appeal.

Chairman, The Centre for Enterprise, Markets and Ethics

Biography of Guest

Summary of Interview. Name of Interviewer with link

Centre for Enterprise, Markets and Ethics

We have compiled some news, comment pieces and announcements that we hope our readers find interesting. In this instalment, there are stories relating to artificial intelligence, utilities, defence spending, public finances and the cost of borrowing, virtue and commercial success, pensions and the environment:

Artificial Intelligence

Artificial intelligence shows great potential for transforming businesses and generative AI models are used by millions of people each week, yet companies who have invested in AI pilot products are struggling to make effective use of them, with some 42% having abandoned projects in the last year. Disillusionment can stem from a lack of suitable IT infrastructure at the company purchasing the technology, a lack of available expertise to make the AI model effective or a fear reputational damage in the event of an AI failure. There are implications for the large scale developers as well as the companies that make use of their products but the question for each is the same: how can generative AI be usefully integrated into businesses in order to produce worthwhile returns on investments?

https://www.economist.com/business/2025/05/21/welcome-to-the-ai-trough-of-disillusionment

Evidence of AI-imposed unemployment is scant, with figures and research remaining inconclusive when it comes to the question of whether technology is driving redundancies. In leading economies, unemployment remains low and wage growth is reasonably strong. Perhaps, therefore, those companies who announce investment in AI are not using the technology for ‘serious’ work, or, when companies do adopt artificial intelligence, they do not let people go; rather, AI is used to assist rather than replace employees:

https://www.economist.com/finance-and-economics/2025/05/26/why-ai-hasnt-taken-your-job

It seems that artificial intelligence is disrupting employment in the technology sector, with numerous announcements of staff redundancies. However, further large scale lay-offs appear unlikely as new projects involving AI will take time to develop and be put to use (if they are not abandoned prior to implementation or subsequently reversed). In addition, new roles are likely to be created in order to use and manage artificial intelligence:

https://www.ft.com/content/cb9ea970-e6de-4daf-aa9e-7a48d5e648c3

‘Vibe coding’ enables people with no expertise in coding to create basic apps or games by giving basic instructions in natural language to large language models, which then produce an approximation of what has been requested, with the user then in a position to request amendments. Will this make it easier for people with ideas but insufficient technical expertise to launch start-ups, or for companies to engage in technical development without having to hire professional coders? Perhaps individuals will be able to create their own, personalised apps without having to buy or subscribe to existing offerings. Others criticise the lowering of barriers – but it remains to be seen whether this is self-interest or simply insight into the limitations of what can be achieved without genuine technical skill:

https://www.ft.com/content/f4f3def2-2858-4239-a5ef-a92645577145

Environment and Sustainability

Technology companies, banks and shipping companies are investing in a new method of reducing carbon emissions that involves spreading crushed silicate rocks onto farmland in order to increase the surface area of the rock, thus mimicking and accelerating a natural reaction between absorbent rocks and rainfall. As polluters look for methods to reach net zero targets, ‘enhanced rock weathering’ is growing in popularity and stands behind certain forms of carbon credit:

https://www.ft.com/content/ffc2d60d-49fd-4d8c-ba2f-ee55b0447dff

An area of debate surrounding renewable energy is that of zonal pricing, whereby different rates of electricity are charged according to local supply and demand dynamics. Those in heavily populated areas would pay more, while those closer to sources of energy, such as the wind farms in Scotland, would pay less. The idea is that a zonal mechanism would address inefficiencies in the existing network while also encouraging the location of solar and wind farms close to places of high demand. Arguments for and against zonal pricing centre on the likelihood of businesses relocating to areas of abundant renewable energy, the possible effect on overall prices resulting from uncertainty among energy providers about the revenue likely to be generated by a zonal system and the level of waste in the current system, whereby wind farms are paid to stop generating in order to avoid overloading the grid, with gas plants being paid to provide for consequent shortfalls elsewhere:

https://www.telegraph.co.uk/business/2025/06/06/net-zero-rebellion-spark-action-keir-starmer/

Utilities

Thames Water has been fined a total of £122.7 million by the water regulator, Ofwat, for breaches of rules relating to its wastewater operations and the payment of dividends. Given the company’s level of debt, further penalties for failures in performance may deter future investment and ultimately result in the company falling into special administration, which would amount to renationalisation:

Public Finances and Interest Rates

With global economic conditions now being somewhat closer to how they were before the 2008 financial crisis, is it a mistake to expect that interest rates can be kept low? Along with increasing trade barriers and a reduced glut of savings, the world is also witnessing inflationary pressures such as labour shortages caused by ageing populations and shocks such as the war in Ukraine, as well

as increasing government debt. How will governments adhere to their commitments in a range of areas if the age of cheap money is coming to an end?

Pension Reform

The Pension Schemes Bill contains measures designed to encourage pension schemes towards more adventurous, UK-based investing and there have been claims about the extent to which this will increase the value of the average British worker’s pension as a result. However, are these claims – and the Bill itself – based on sound predictions regarding returns on investments? If a great deal of cash is suddenly invested in any asset, returns usually fall over the longer term and it is far from clear that investment in infrastructure – one of the sectors that is favoured for investment, alongside private equity and private debt – is reliable at present. Has the modelling for the predictions been based on unjustified assumptions about continuing returns from these sectors on the part of those whose own pensions will not be subject to their performance?

Defence Spending and Growth

With countries across Europe loosening their fiscal rules in order to increase their defence spending, the UK government has announced an aspiration for defence spending to reach 3% of GDP by the next parliament. Whether this will emerge as a source of jobs and prosperity will depend on how the additional funds are used. One suggestion is that over several decades, prioritising research and development in defence technologies by supporting start-up companies will yield better results in terms of raising the national income than will spending on personnel and equipment. Others have questioned whether increased military spending will have any serious effect on the creation of jobs in a sector which accounts for only 0.9 per cent of jobs in the UK and in which expenditure has increased marginally since the 1980s but employment has fallen by half:

Purpose, Virtue and Commerce

Might companies with a better sense of purpose, structures that lend themselves to success in what that company was set up to do and the exercise of what philosophers such as the late Alasdair MacIntyre would describe as virtues or excellences – shared values, goals and practices – be more enduring and ultimately more successful than those that focus narrowly on profit-maximisation alone?

https://www.ft.com/content/591ee1f2-2518-4ca4-a128-3c810f965782

A fascinating advance currently underway in the field of artificial intelligence is the development of models to assist with peace negotiations. In collaboration with the White House, a think tank in Washington has been developing a simulator that generates potential peace-agreements to end the war in Ukraine, and also scores the likelihood of each deal being accepted by the combatants and other stakeholders. Another project, the development of which is based on a partnership between the British Foreign Office and the University of California, Berkeley, is aimed at providing advice for negotiators by generating a range of possible ‘voices’ or perspectives. The idea is that the AI model will enable officials to anticipate possible responses from various parties, whether superiors back home or hostile interlocutors. This presents the possibility of their being prepared to reframe negotiating positions quickly and to maintain momentum in talks.

AI Hawks, AI Doves

Interestingly, in test runs of different negotiating models, some have proved to be rather escalatory, opting to use force too readily, while others have been somewhat risk averse – or overly conciliatory. What does it mean to say that an AI negotiator is too escalatory or excessively conciliatory? Such judgements make sense to us, but in what sense can we attribute these qualities to machines? Obviously, an AI model has no conscious grasp of a conflict situation or what is at stake for the various parties involved, so there is no sense in which it can really be either risk-averse or hostile. All that we can mean, therefore, is that its coding is such that it produces certain types of output in response to specific types of input. The important point here is that these judgements are human: an AI model can only be escalatory or conciliatory in our opinion, relative to our own perception of a situation and the ends that we wish to achieve. To say that a machine is too ready to resort to force means only that in the same situation – and given the manifold ends in view – we would have made greater efforts and perhaps been willing to concede more in order to avoid such an outcome.

The Human Factor

Artificial Intelligence models can of course be trained or programmed to respond differently. Indeed, there are projects underway to improve the responses of AI negotiation models, one of which aims to convert information about appropriate and inappropriate human language and actions into code. Thus, the aim is to render the model more human and to respond in a manner closer to our own. However, it is not clear what this would entail. As has been demonstrated in several contexts recently, negotiation is complex and there is no straightforward ‘human’ response to resolving conflicts. Different parties, while agreeing that they desire peace, will take radically positions on what the conditions are to be.

This, however, is the point: however sophisticated any negotiating model might become, however apparently human and however capable of foreseeing possible responses and generating alternative proposals, it can only function on coding based on our own preferences and judgements (or those of the parties by whom it has been trained). In matters of politics and in morality, complete neutrality is all but impossible. There is no such thing as complete objectivity or an objectively optimal outcome. Any outcome must always have its foundations in the judgement of the parties involved, and their weighing of considerations such as national interest, what constitutes a fair settlement, the significance of environmental damage, the value of human life and the availability and best use of resources, together with the strength of their desire for prosperity and peace rather than conflict.

For this, certain virtues ought to be exercised and we always hope for the display of qualities such as prudence, wisdom, justice and moderation. As excellences of character cultivated over time, these are uniquely human and cannot be possessed by machines. Where artificial intelligence can support leaders and negotiators in achieving peace, it is to be welcomed, but decisions can only ever be made by human beings exercising their faculties of judgement, hopefully informed by the requisite virtues – qualities of character that can shape the training of AI models, but never be replicated or replaced.

Neil Jordan is Senior Editor at the Centre for Enterprise, Markets and Ethics. For more information about Neil please click here.

Image courtesy of Freepik (www.freepik.com)