Maurice, Baron Glasman is a political theorist, academic, social commentator, and Labour life peer, best known as a founder of Blue Labour. He is Senior Lecturer in Political Theory at London Metropolitan University, Director of its Faith and Citizenship Programme and a columnist for the New Statesman, Unherd, The Tablet and Spiked.

We are moving from an era of contract, of globalisation, of the rule of lawyers, into an era of restoration, of the nation state and of covenant: an age of borders and belonging, of solidarity rather than diversity, of weapons production rather than TV production – a time when the working class have found their voice once more and will not be stilled.

Pope Francis said in a rare moment of clarity that we are not living through an era of change but a change of era. About this he was profoundly correct. I attended the inauguration of President Trump last January and that confirmed my suspicion that the old era of progressive globalisation, mercilessly initiated by Margaret Thatcher and immaculately consummated by Tony Blair, in which markets are good, privatisation is good, free movement of everything all the time is very good, when mass immigration is good, not only for the economy but for all of us because diversity is good… all of that is over. The era initiated by the Brexit referendum is now in full swing. We have already witnessed a government, and possibly an entire great political party, grievously wounded by its inability to grasp the meaning of sovereignty and the possibilities of Brexit. The wound is grievous; it could yet be fatal. The same is true of this Labour government. If it cannot move from the contractual to the covenantal, it will suffer the same fate.

Sovereignty and Globalism, Covenant and Contract

During a change of era, concepts that were considered redundant or outdated take on a new relevance. One example was sovereignty, which was considered obsolete in the era of globalisation, but which had a durable power to influence and frame political debate during the Brexit referendum, and is now perhaps the central dividing line of politics. I divide the world between ‘sovereigntists’ and globalists, between common law and human rights.

Similarly, another concept that was considered antiquated and irrelevant, but which will play a central role in shaping the new era, is that of Covenant, which should displace contract as the primary way of conceptualising the difficulties faced by our society, in order to frame a new settlement that will overcome the underlying weaknesses in our economy and politics, and which any government must address if it is to be successful.

A covenant is a binding agreement that establishes a partnership between generations, interests and regions. It establishes legitimate and sovereign institutions which reinforce and uphold the obligations and benefits of Covenant across time and space. It binds people into a society built around the common good.

As a partnership that endures over time, no one part of the covenantal compact is sovereign: each part is essential for its functioning, being based on mutual respect and shared benefits in the form of power, responsibility and accountability.

It is not difficult to understand the power of Covenant in our polity. We are a hybrid nation, part contractual, part covenantal. For example, Parliament is a covenantal institution that is intergenerational, composed of representatives from different regions and interests. Its laws are binding unless repealed. The fuss around the Henry VIII Laws, for instance, is an indication of this. The Monarchy is covenantal and, indeed, the King as Head of State rules in Parliament, which is the source of both executive and legislative authority. The Bishops sit within it, as do the Law Lords, who, with the Attorney General, uphold the authority of the Common Law, which is also a covenantal inheritance and underwrites the authority and legitimacy of the law. We are an ancient country that is bound by ancient institutions. The old universities, self-governing corporations committed to the pursuit of knowledge, were once part of that covenant, as were the Church of England and the City of London: they are a plurality of institutions committed to the common good of the nation with specialist roles within it.

Covenant-Based Politics, Contract-Based Economy

Whereas our politics are covenantal, our economy is contractual. When the logic of a market economy has been injected into the rest of society, it continuously undermines the covenantal bonds: witness how the Prime Minister recently spoke of ‘an island of strangers’, an oddly evocative remark for such a prosaic man.

Due to the primacy of contract as a way of distributing power and authority, a very big problem has developed within our economy and society, which has now become a political problem. With the election of Margaret Thatcher in 1979, the sovereign prerogative was given to capital alone to decide on matters of strategy and investment within the economy, and this led to the degradation of work and labour – the commodification of the human being, the desecration of Creation. People felt a sense of humiliation and abandonment, which led to a polarised politics and despair.

The relationship between contract and capital has led to the domination of one part of society over another through concentration of ownership, and that is harmful for a society in the covenantal tradition. It has led to the explosion of debt, both personal and public, which is hostile to mutual dependence and leads to domination. It leads to an obscuring of the idea that we are stewards of our natural inheritance, not its owners. Covenant, by contrast, binds people in mutual obligation to the flourishing of our natural environment.

Trusts could be an existing way of conceptualising the covenantal approach to upholding the internal good of our environment, rather than its external value in the form of money. If forests, rivers and parks are endowed in the form of trusts to the care of local communities then the natural environment can be bound within the covenantal framework. If trusts were to be established for our utilities, they would offer an alternative to nationalisation or privatisation for the organising of utilities.

In practical terms, this means that capital would be required to build alliances with others, to negotiate a new settlement in which capital is important but not dominant. The changes in politics in recent years means that it needs to build coalitions with other businesses, with government and with society as equal partners in the covenantal coalition.

Capital is in some sense a shared inheritance that includes the labour and contribution of previous generations in the development of value. It is, however, fungible and privately owned and in its permanent demand for higher and quicker returns would feel constrained and limited by the obligations that Covenant demands. Capital can easily move out of relationships and start to exploit people and planet. It is a source of dynamism and value – but also of disruption and desecration. A clear example is its relationship to the elements of Creation itself, human beings and nature, which it considers as factors of production, to be used exclusively in the service of profit. In contrast, Covenant, by upholding a partnership through time, can ensure that the status and dignity of labour is upheld and the integrity of our natural environment preserved.

The covenant is built around the distinction between dependence and domination. We are all, by our nature, dependent on other people and our natural environment for our life and wellbeing. We are dependent on the fulfilment of mutual obligations and the honesty of the work of others.

Contract allows for the asymmetries of power to be reproduced and for the exclusion of the concerns of others to be upheld. Covenant, on the other hand, addresses the inequalities of power that contract upholds. It seeks to avoid the domination of any one part of society, of the economy, over other parts. This requires a new institutional settlement built around the idea of the common good, that we all benefit from the beneficial constraints that Covenant provides.

How Covenant Works For Us

Labour is in a mess and has lost the affections of its heartland voters. It is confused as to how to respond. It has little conception of how to build a winning coalition. It seems incapable of articulating what is wrong, how to change it or to speak in a language that resonates with voters.

The idea of Covenant can provide an organising principle of national restoration.

A covenant is a binding commitment to reconcile estranged interests in a decentralised institutional settlement that has multiple constituent elements:

In summary, Covenant speaks to a durable new settlement within which place, participation and work play a fundamental role.

Danny Kruger has been the Member of Parliament for East Wiltshire, previously Devizes, since 2019. He became David Cameron’s chief speechwriter in 2006, whilst Cameron was Leader of the Opposition. He left this role two years later to work full-time at a youth crime prevention charity that he had co-founded called Only Connect. For his charitable work, Kruger received an MBE in 2017. He was Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s political secretary between August and December 2019 and became Shadow Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State for Work and Pensions in November 2024.

Instead of a social contract, an imagined deal struck in the light of ‘reason’ between the sovereign individual and the totalising state, we need a social covenant. This word is difficult. Its origin is in the peace treaties and tribal agreements of the ancient Near East, adopted and adapted by the people who became Israel to explain their relationships with God and with each other, and in due course with the land they inhabited. It defines a model of political organisation that is deep in the foundations of the West, and of the United Kingdom in particular. Put most simply, the politics of the covenant is built not on reason but on love.

The meaning of the word has been well conveyed by the phrase ‘artificial brotherhood’.7 A covenant is a way of expressing and formalising the love – unconditional, unstinting, permanent – that can exist between people who are unrelated by blood. The foundational social covenant is marriage, the union of two unrelated people that forms the nucleus of a new blood relationship, a family. Other covenants, less obvious and discrete, work in the same way.

Just as families are made by the covenant of marriage, so places – human communities situated in a geography – are made by the covenants of civil society, the formal and informal institutions and associations through which the people of a neighbourhood achieve agency and belonging. Nations, meanwhile, are formed by the covenant of statehood, the mysterious complex of powers, ceremonies and institutions in which a people recognise, authorise and confess allegiance to their country.

In each of these covenants something real is acknowledged: an elemental and important thing is honoured, made safe and put to a social purpose. The goal of the marriage covenant is to make sex safe – to reduce its capacity to wreck relationships and produce unwanted babies – making it the foundation of a family. The covenant of place, the local arrangement of civil society, honours the land, and makes on a patch of earth a community that regulates and, through local economic activity, sustains itself. And the covenant of statehood, in Burke’s phrase, ‘makes power gentle, and obedience liberal’: it tames the fact of violence, the capacity of the strong to dominate the weak, and so creates a nation, which is something not merely to fear but to be loyal to, even to fight and die for.

The covenants of family, place and nation share a set of qualities. Being rooted in physical reality – sex, land, violence – they reflect the nature of things, and thus transmit the ordinary affections that people feel towards their family, their neighbourhood and their country. Crucially, though, they create communities of difference. A covenant is essentially heterogeneous. This is true in marriage, where the partners come from different families and each bring their own idiosyncrasies and identities to the creation of this new thing. It is true in neighbourhoods, which are naturally diverse: as Andrew Rumsey has pointed out, the Greek ‘paroikoi’, the word from which we derive ‘parish’, means someone outside the household, a stranger to the people. The parish is a community of the unrelated, with an obligation to the outsider. And the same goes for nations, or at least this nation. The British are bound by something quite other than blood; ours is a civic not a racial nationalism, an ‘artificial brotherhood’ forged by centuries of peaceful enjoyment of the common inheritance to which all newborn citizens, whether ethnic Saxons or Afghans, are equal heirs.

The heterogeneity of a covenant is resolved in a further quality. A covenant, unlike a contract, does not simply force competing interests into a legal arrangement by which each expects to profit, and in which each remains essentially an adversary. A covenant aligns interests, including the interests of those who are not direct parties to the arrangement, such as future generations or the natural world.

The essential difference between the ‘social covenant’ we need and the ‘social contract’ we derive from Hobbes and Locke is that the relations of a covenant have the quality not of choice but of givenness. A covenant is not created by your consent, but sustained by your assent to it. You join something that existed already – this is so even in marriage, where you join ‘the married state’ whose terms and conventions, and indeed the form of the ceremony that admits you to it, are laid down in advance. Indeed even in marriage, where the relations begin in choice, the choice takes the form (at least in pretence) of an assent to the only choice that is really possible: a yielding to the compulsion of love.

The meaningful choice in all these covenants is not whether to enter but whether to leave them. You are always free to change your nationality, leave your neighbourhood or divorce your partner. But the expectation is that these are commitments that matter, and indeed they keep their hold on you even if you walk away. The covenant itself might be broken but the thing it makes – the family, the community, the nation – endures, with you part of it. You can never entirely renounce the land and place of your birth, and a divorce does not cancel the responsibility you have to the person you once loved and promised to care for, and certainly not to the children you made together. A covenant is not conditional, like a contract, where one party can renege if the terms are broken. It is an ‘artificial brotherhood’. Like a blood relationship it cannot be undone, and where there is a permanent breach there is lifelong regret.

The covenant gives us a common conception of the good, a language in which we can understand each other and a sense of collective endeavour towards a better world which we can all imagine. And it gives to each individual the proper ground of personal freedom: it is the ‘strong base’, in the words of the child psychologist John Bowlby, for ‘bold ventures’.

We have compiled some news, comment pieces and announcements that we hope our readers find interesting. In this instalment, there are stories relating to artificial intelligence, free trade and the environment:

Robot bricklayers that can work round the clock coming to Britain (The Telegraph)

Following success in the Netherlands, robot bricklayers will be tested on building sites in the UK as of next month in an attempt to address a shortage of bricklayers. The machines work at a similar rate to a human bricklayer with a predictable output, and two machines can be supervised by one human, who need not be a bricklayer. The contractor using the robots does not believe that the machines will ever fully replace human tradesmen

The AI job cuts are accelerating (Financial Times)

Tech companies appear to be cutting jobs. In the past when companies laid off staff, this was considered regrettable; now, in some sectors, it is considered a sign of progress. Artificial intelligence is not the only reason for this but it seems to be making certain roles obsolete, in spite of claims that it is redesigning rather than replacing jobs. What does it mean for traditional career pathways when entire rungs on a career ladder are disappearing? Will university degrees retain their value? And will ‘leaner’ companies necessarily be better? They might be more efficient and perform well financially, but what will become of creativity, customer service and resilience when shocks occur?

The world court joins the fight over climate change (The Economist)

The International Court of Justice (ICJ) in The Hague has issued an advisory opinion that appears to make environmental protection an issue of human rights protection, which would oblige states to set ambitious targets to protect the environment, regardless of whether they have signed up to treaties for this purpose. Failing to protect the environment adequately, for instance when states subsidise the production of fossil fuels or fail to rein in polluting companies, could constitute an internationally wrongful act, thus rendering nation states liable for environmental harms and potentially subject to claims from countries who consider themselves to have been harmed by climate change

The remarkable rise of ‘greenhushing’ (The Economist)

Companies used to be accused of greenwashing. Now they might be described as engaged in greenhushing. Headlines suggest that business has turned against the fight against climate change but surveys indicate that relatively few have actually reduced or abandoned climate targets, while most have either adhered to their own pledges or enhanced them. The difficulty is that where targets have been diluted or abandoned, this has occurred in sectors central to mitigating climate change, while political influences in some countries, particularly the US, render it more difficult for businesses to pursue – and openly announce – climate goals

The humbling of green Europe (The Economist)

Has Europe passed the high watermark of climate action? Governments recognised as moderate or centrist now seem to be turning away from climate mitigation. While European public opinion still considers the environment important, other concerns, such as the cost of living and defence have led to the climate falling down the agenda, particularly given the costs associated with net zero targets. A further problem is that while progress so far has been encouraging, it has focused largely on industry and energy generation, in the form of carbon trading markets, for example. Further measures will fall on ordinary businesses and households and may meet with greater resistance. One approach to encouraging people to see climate regulations more positively would be via simplification or relaxation of rules, or providing the means for states to favour businesses that invest in green technology – but lifting red tape and providing governmental support are criticised for potentially allowing more environmental degradation and imposing further costs on consumers. Another approach is to allow flexibility in schemes that exist, so that areas struggling with reform are given more time to meet emissions targets as other sectors decarbonise more quickly

The climate needs a politics of the possible (The Economist)

It is one thing to state ambitious climate targets and enshrine them in law but another actually to meet them. How can this be achieved given the costs and the rising scepticism among individuals about whether strict targets and green measures are either in their personal interest or actually achieve any clear benefits? Perhaps the answer is a combination of taxation or charging for pollution (where this is not too unpopular), subsidies for avoiding pollution in the first place (and the removal of subsidies for polluting industries) and measures to ensure that change does not fall too heavily on ordinary people, perhaps by providing the means and infrastructure to make desirable changes possible for them

The hidden net zero tax crushing British industry (The Telegraph)

Introduced to disincentivise emissions when the carbon price fell during an industrial slump, the ‘carbon price support’ remains in place over a decade after its introduction and is now over four times higher than when first mandated (now £18 per tonne, up from £4.94 in 2013). Since it applies to gas as well as coal, and as gas power stations set prices for energy markets, this has serious implications for industrial costs and domestic energy bills. Other features of the UK’s carbon trading scheme has led to complaints of upward pressure on costs and an inadequate supply of alternative sources of energy for industrial users, resulting in a lack of competitiveness with overseas businesses that do not face the same charges

American businesses are running out of ways to avoid tariff pain (The Economist)

According to some estimates, American businesses are absorbing up to three-fifths of the costs of recently imposed import tariffs rather than passing them on to customers, but many are looking for ways to lighten the impact, whether by stockpiling goods, adjusting supply chains or shifting manufacturing so as to import from other locations, or seeking rulings on where goods produced across various locations will be judged to have been imported from

On Monday 14 July, CEME held an event with guest speaker Dylan Pahman (Acton Institute).

Organised in partnership with Blackfriars Hall, Pahman spoke on his forthcoming book The Kingdom of God and the Common Good.

The event was chaired by Andrei Rogobete.

Speaker Bio:

Dylan Pahman is a research fellow at the Acton Institute for the Study of Religion & Liberty, where he serves as executive editor of the Journal of Markets & Morality. Dylan recently completed his PhD from St. Mary’s University, Twickenham on the basis of his published works on Orthodox Christian social thought and asceticism. He is the author of Foundations of a Free & Virtuous Society (Acton, 2017) and The Kingdom of God and the Common Good: Orthodox Chrisitan Social Thought (Ancient Faith, forthcoming 2025). In addition to Orthodoxy, his research also touches on the Dutch Neo-Calvinist Abraham Kuyper, the Anglican Christian socialist F. D. Maurice, and the intersection between ethics and economics. Dylan is a member of the Greek Orthodox Metropolis of Detroit and resides in Grand Rapids, Michigan with his wife Kelly and their four children.

(This is the Conclusion to Private Planning and the Great Estates (2023) split into five web-friendly sections)

See: Introduction, Chapter 1, Chapter 2, Chapter 3

What lessons are to be learnt from the great estates and their role in the development and redevelopment of London?

The physical development of a city is not, as is often supposed, merely another aspect of its economic activity. Decisions on the use of land are absolutely fundamental to the way people live on it. The nature of property ownership, the extent of public control, the styles of streets and buildings, the whims, fashions and pecuniary ambitions of land holders, all dictate not just the city’s appearance but the social behaviour of its inhabitants.1

The first lesson is historical, namely that within the inner-London estates there was something resembling the best ideals of urban planning. Through a series of legal mechanisms and pecuniary – and perhaps reputational – incentives, the estates, architects, builders and others composed some of the most impressive parts of urban London. The image of Victorian London teeming with disease and privation must be set against that of middle-class London. The dimensions of this historical lesson bleed over into institutional economics and the capacity of markets to create their own systems of governance. This is relevant to the second lesson from the history of the great estates, which is contemporary and comparative-institutional, namely that the estates form one aspect of a broader case study of soft-touch regulation interacting with dynamic market forces in a large city.

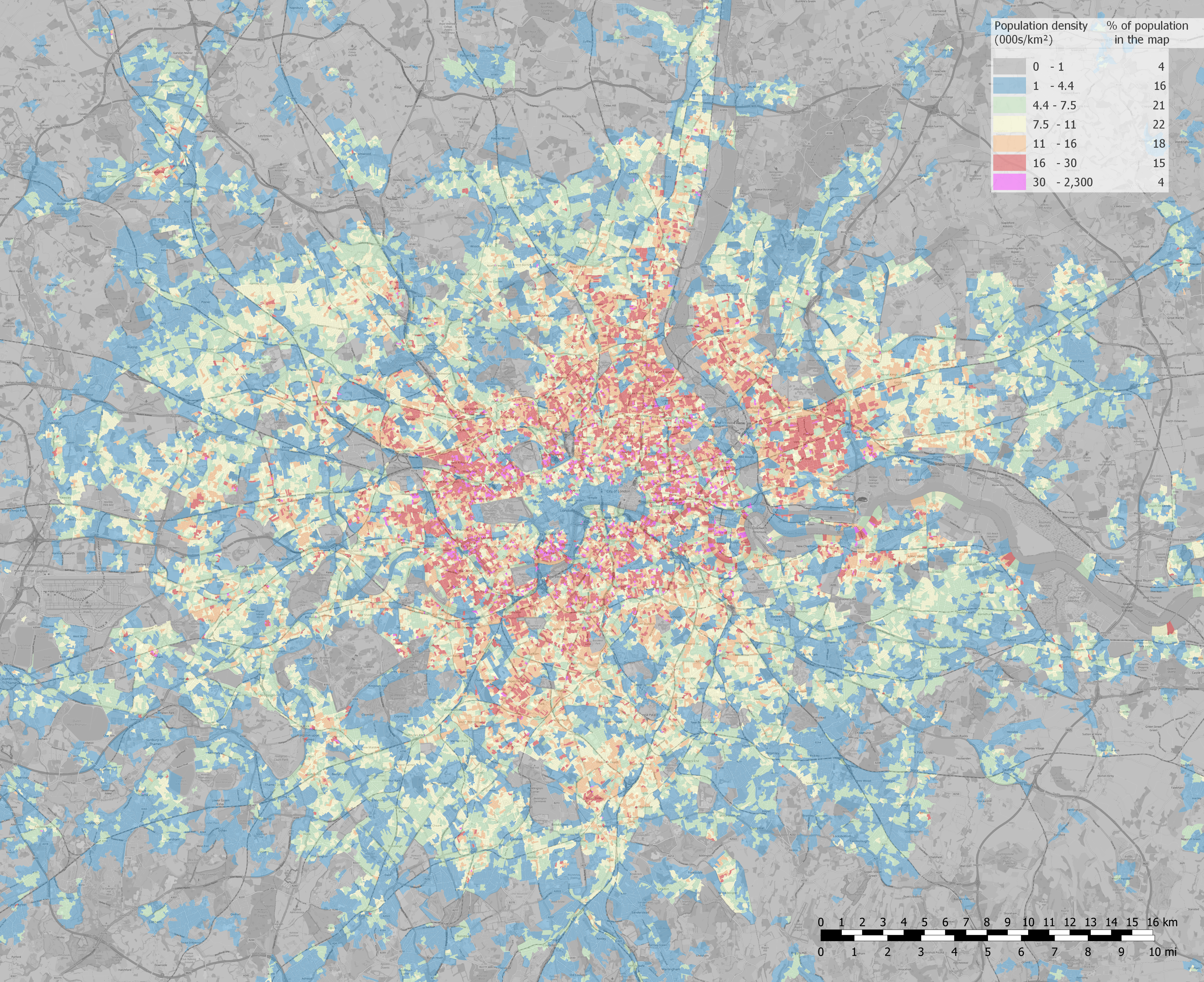

Across the developed world some of the most productive areas – that is, cities – are the most incapable of building more, which has sizeable and widespread ramifications. The living standards of those who can afford to live in them are affected by artificial scarcity of living space. More than this, the types of urban design prevented by regulation are the very ones most carbon friendly and associated with other sociological benefits.2

Economic theory and historical examples shed light on what would happen in different regulatory environments and thereby inform debate about this important topic. London, especially in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, offers an excellent case study for both historical and institutional reasons. Over this period London was the centre of the world and became its most populated city. Its continuing growth was unprecedented. Although it is still a global city and the largest in Europe, inner London is still significantly less populated than it was a century ago. This is related to the institutional point that the history of London allows observers to see the self-organising and self-regulating nature of individuals and markets. Both in development and redevelopment, the ability of private contracting to result in positive outcomes is much stronger than many would expect. With large landowners in particular, the internalisation of spillover effects gave positive results, such as provision of green space and aesthetically cohesive planning, while negative effects, such as odious trades, were prohibited. Much of this occurred in the shadow of government rules but was market rather than public-policy led, especially in areas with middle- and upper-class tenants. The peculiarities of the concentration of London landowning offers a clear illustration of the benefits of large-scale landowners that internalise many spillover effects and reduce transaction costs associated with redevelopment.

Lessons of and potential for intensification

Contemporary London faces a housing shortage. Despite the rise of remote work and the pandemic-induced decline in rents, rents in 2022 reached new heights. Relatedly, house prices within London and surrounding areas have grown faster than wages, and homeownership lies increasingly out of reach of even white-collar professionals. The political economy of the situation is difficult. The current system of land-use regulation asks existing homeowners to allow nearby house building while offering concentrated costs and at best diffuse benefits.3 Development often brings noise, more traffic and loss of open space while offering few benefits to the individual (despite larger social benefits). It is no wonder that new projects get bogged down, diluted and drowned. The political reality of extensive development is perhaps more difficult than that of urban intensification and regeneration in London. Recent regenerations include council estates and increasingly mixed-use developments built by, for example, British Land and London Docklands. Some see such actors as inheritors to the great-estate tradition.4 The continued shortage of everything from lab space to housing shows that this is not enough.

Policy advocates such as Samuel Hughes and Ben Southwood suggest new regulatory procedures to change the pay-offs facing stakeholders and replicate some of what incentivised the estates in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.5 They argue that their proposed rules:

offer a way of replicating effects [of the great estates] under modern conditions. As part of the block plan process, residents set a design code governing any permitted building. Because design is thus determined at the level of the neighbourhood rather than the individual plot, residents will be incentivised to maximise value across the neighbourhood as [a] whole – rather than maximising it on each individual plot, potentially to the detriment of its neighbours. Block plans, implemented through street votes, thus offer a middle way between an architectural free-for-all and the imposition of rules by the state, potentially yielding a generation of popular and beautiful urban architecture.6

As the authors note, estimates suggest that ‘if London were intensified to the densities of the historic areas of Paris within the Périphérique, it would accommodate around forty million people.’7 It is not necessary to go to Paris to appreciate that some of the best-loved parts of London, built by the great estates, manage to combine density and liveability with economic and social benefits.

Notes to Conclusion

2 Ramana Gudipudi et al., ‘City Density and CO2 Efficiency’, Energy Policy 91 (April 2016), pp. 352–61; https://doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2016.01.015; Sam Bowman, John Myers and Ben Southwood, ‘The Housing Theory of Everything’, Works in Progress (blog), September 2021; https://www.worksinprogress.co/issue/the-housing-theory-of-everything.

3 See Mancur Olson, The Logic of Collective Action: Public Goods and the Theory of Groups (Cambridge, MA and London: Harvard University Press, 1965).

4 Sarah Yates and Peter Murray, Great Estates: How London’s Landowners Shape the City (London: New London Architecture, 2013), p. 005.

5 Ben Southwood and Samuel Hughes, ‘Strong Suburbs’ (London: Policy Exchange, 2021), https://policyexchange.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/Strong-Suburbs.pdf; Ben Southwood and Samuel Hughes, ‘Create Mews’ (London: Create Streets, 2022), https://www.createstreets.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Create-Mews.pdf.

6 Southwood and Hughes, ‘Create Mews’, p. 36.

7 Southwood and Hughes, ‘Create Mews’, p. 31.

(This is Chapter 3 of Private Planning and the Great Estates (2023) split into five web-friendly sections)

See: Introduction, Chapter 1, Chapter 2, Conclusion

Parts 2 and 3 emphasised the historical role of private planning in the development and redevelopment of modern London, and argued that it had some of the benefits often claimed for regulated systems, such as responding dynamically to changing circumstances and solving externality problems. This chapter traces the role of the state in regulating the development of urban London, showing how state power changed in both degree and kind. It locates this change within the perceived failures of the market, technological changes and the general rise in statist thinking about public planning. In conclusion it discusses current failures of the planning system, identifying opportunities for reform in light of lessons from the great estates.

At approximately the same time in the early twentieth century, the rise of social housing, emergence of mass owner-occupancy and continuation of rent control caused a collapse in the leasehold system. In the interwar years, private developers built an astonishing three million homes, mostly on farmland around Britain’s cities.1 But by mid-century, new regulations and the lingering economic effects of the Second World War had reduced the market-built housing sector to a shell of its former self. The 1947 Town and Country Planning Act nationalised the right to build, while urban green belts limited the extensive growth of cities.

Over the intervening years the Conservative Party, in particular, has sought to liberalise the market. The conversion of public housing into private benefitted a generation of existing tenants but failed to spur the type of supply-led changes needed for housing costs to come down. The financial regulations brought in after the financial crisis are also seen by some to have further hamstrung younger potential buyers.

The benefits of the private planning of development and redevelopment as practised by the great estates were shaped by the institutional context of Georgian and Victorian London. To outline that context is no easy task. Prior to the 1889 creation of the London County Council (LCC), municipal governance consisted in a maze of local ‘vestries’ following parish boundaries. Only the City and Westminster – the former more important in terms of both population and economic heft – were unified. The earlier Metropolitan Board of Works (MBW), created in 1855, pulled some public services together across the region, including new sewerage for areas not served by the existing City of London system. The MBW also carried out slum clearance and roadworks. Initially these occurred concurrently because its slum-clearance powers depended on roadworks or other improvements, though over the nineteenth century, various Acts strengthened those powers. But in general there was little local planning apart from private planning by landowners and/or developers.

Despite this, the development of the great estates and the freehold lands surrounding them did not take place in the absence of regulation. The national government regulated building in various ways – some rulers even tried to ban all construction of dwellings around existing London. As Nicholas Boys Smith explains:

Under pressure from London’s Mayor and Alderman, four successive monarchs and the Parliamentary Commonwealth all attempted to prevent building beyond the city limits. At least three Acts of Parliament, nine Royal Proclamations and innumerable Orders in Star Chamber and letters to and from the Privy Council attempted to ban the construction of new building within one, two, three or five miles of the City Gates and of Westminster (details changed over time).2

Based on other sources, Boys Smith argues that the 1660s transformed London: attitude as well as policy changed from regulating the principle of building to regulating its manner and method – a useful distinction.3

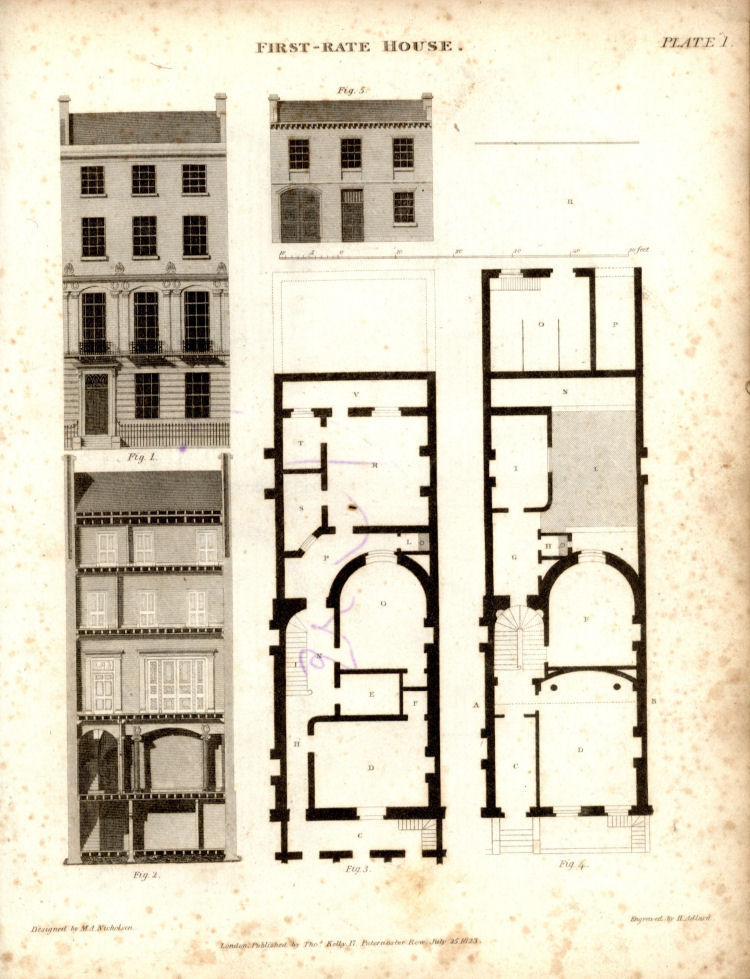

The Great Plague (1665) and Fire (1666) cleared the City of London itself of much of its medieval architecture. Although lofty plans for rebuilding along continental lines were drawn up, for a number of reasons they were not pursued.4 What did come about was the 1667 Rebuilding of London Act, which set out regulations for the City. These would ultimately be extended to Westminster and the rest of growing London, and included the standardisation of development into four ‘sorts’.5

In the aftermath of the Fire, various building Acts were passed to limit the types of building features that contributed to the spread of fire. Those of 1707 and 1709 banned wooden ornamentation, such as cornices, and stipulated that window frames be recessed – both in the interests of hindering the spread of fire.6 The entire system was overhauled in the late eighteenth century with the Building Act (1774), which applied to London and was extended to other cities.7 This introduced not only further regulations concerning exterior wooden ornamentation and the construction of windows but also a system of housing classification.

Under this, four ‘rates’ of houses related to the size of each floor and the type of street. For example, First Rate houses were defined as valued at over £850, with floorspace of more than 900 sq. ft,8 while Fourth Rate houses were valued at less than £150, with floorspace of less than 350 sq. ft.9 Alongside each rate sat different requirements for thickness of walls, among other things; but of major importance, as John Summerson and later writers agree, was that this system of regulation also ‘confirmed a degree of standardisation in speculative building’, so that references to rates became common in agreements between estates and builders.10

The first real overhaul of the 1774 legislation did not come until 1844, with the Metropolitan Dwelling Improvements Act. Over the rest of the century the tendency was towards measures increasing minimum street width and space between buildings, as well as decreasing density and addressing public-health concerns.11 Height restrictions were determined in part by the width of the streets and were strengthened in London after the construction of increasingly tall residential buildings along Victoria Street.12 In addition, the derived by-law regulations stemming from Public Health Acts increasingly regulated the form of housing in the UK, encouraging lower net density than earlier working-class housing as streets became wider. Over the second half of the nineteenth century and first half of the twentieth, these types of control were tightened as demands for regulation continued, but other forms of state involvement grew alongside them. Nevertheless, Boys Smith13 notes that developments that met the rules could not be refused; there remained an implicit right to build.

By the middle of the nineteenth century the regulation of construction was just one aspect of state involvement in housing and housing markets:

Perceptions as to what constituted intolerable overcrowding varied between cases and between countries. England, almost certainly having the least congestion, was more concerned with overcrowding as an evil than either France or Austria and was far ahead of any continental country in providing philanthropic and municipal housing.14

Public-health crises, particularly those stemming from cholera epidemics, led to the state’s increased involvement. At first this meant more regulation, along with such public works as sewers and roads. Later it included clearance of the worst dwellings and ultimately provision of housing.

One way to view this historical development is to root it in the private philanthropic efforts of the model-housing organisations described in Chapter 2. These and other charitable providers achieved better outcomes through a combination of factors, only some of which were scalable. On the one hand, they built higher-quality housing and instituted practices both to guard against the deterioration that led to slums and to reduce turnover and improve rent-collection methods. They also set up paternalistic controls to limit social dysfunction. On the other hand, they also benefitted from being oversubscribed and so could select tenants in a way that, by definition, was not scalable. The very location of the charitable dwellings – that is, in the wealthier areas – was also carefully selected.15

Various factors conspired to keep the housing of the poor below an acceptable standard. Despite economic growth, incomes were still low. Furthermore, until the middle of the nineteenth century the geographic extent of an urban centre was limited by transport technology in a way it would not be later. Since the British economy industrialised early, it lacked cheaper, more remote housing for workers. When the railways arrived, their physical assault on the existing city went along paths of least resistance: as stations were built in London, as in other cities, they knocked out neighbourhoods that overwhelmingly housed the poor. Similarly the creation of roads by the MBW: sometimes rookeries or slums were targeted; generally though they simply represented the easiest routes along which to build.

These concerns were addressed in various ways during the middle and late nineteenth century by such legislation as the Torrens Acts (1868–82), which attempted to compel owners of slum properties to demolish or repair them, and the Cross Acts (1875, 1879), which allowed local authorities to prepare slum clearance and improvement schemes.16 This clearance also enabled philanthropic operators to acquire sites more cheaply.17 However, on balance it seems likely that all these measures ‘were largely destructive’, as Simon Jenkins illustratively writes, ‘acting as a many-pronged pincer squeezing the poor into even tighter corners of the city’.18

At the same time, the standards deemed acceptable for poor housing quality rose. While this occurred for what now seem obvious reasons, the effect was an artificial scarcity, with the maths of construction cost and ability of tenants to pay not working out favourably. Through various parliamentary reports and works by interested reformers such as Charles Booth, later Victorians developed a detailed sense of the plight of those who coexisted alongside their mannered middle- and upper-class domains. Within the broader historical and geographical context, urbanisation19 neither created poverty, nor was poverty unique to Britain or the nineteenth century. The captivating nature of nineteenth-century poverty in London and other urban centres was not its existence, rather its juxtaposition with wealth.

While the historical debate around standards-of-living changes associated with the industrial revolution, economic growth and urbanisation still rages, it is clear that standards did ultimately rise as a result of sustained economic growth. It is also clear that Dickensian nightmares notwithstanding, millions preferred living in the growing cities to remaining in the country.

Nevertheless, in an urban setting an aggregate of individual buildings of reasonable quality could suffer from problems of drainage and rubbish less likely to afflict rural dwellings, though such matters could be addressed through public works and improvements – as seen in the period properties that survived slum clearance. But for reasons including cost, public-health theories and ideological beliefs about density, the common response was that these were problems that better, lower-density housing would solve.

According to James Yelling: ‘It is generally accepted that 1890–1914 was the formative period of modern British town planning, and henceforth the control of land, and of land uses and land values, became of heightened significance.’20

Already in the nineteenth century the idea that the dispersal of the population was the only way to improve their lot was becoming increasingly popular. Early forerunners of later government efforts include the Artizans, Labourers and General Dwellings Company on their Shaftesbury Park and Queen’s Park estates.21

Legislation in the nineteenth century allowed municipal governments to build social housing, the first example being in Liverpool under an 1864 Act.22 Most publicly supported – if not publicly provided – working-class housing came via the philanthropic model-dwelling providers, who were given land acquired by the MBW and later the LCC through their slum-clearance powers.23 However, this proved expensive and inefficient for housing the working classes.24

Instead, the direction of travel was towards suburban solutions for the working class, as increasingly for the middle. The transportation innovations described in Chapter 2 increasingly allowed the middle classes to choose a suburban and commuting lifestyle, but until 63 the twentieth century the combined cost of rent and fares proved unaffordable to most of the working class. One attempt at addressing this was workmen’s trains (in part required by Parliament), which offered reduced fares on early-morning journeys into London.25

Building first on examples from philanthropic model housing in London and later on visionary employee housing for industrial workers first at Saltaire and then at Cadbury’s Bourneville, public-housing efforts concentrated on urban tenements and, later, suburban cottage- style estates. As Richard Dennis writes: ‘Under Part III of the 1890 Housing Act local authorities were authorised to acquire green-field sites for public housing, and under a further act in 1900 these powers were extended to include land outside their boundaries.’26 The LCC’s four pre-1914 cottage estates were early examples of a type of local- authority development increasingly seen, after the First World War, as the way to provide better working-class housing. Private markets were not deemed able to provide such housing – a view helped little by wartime measures such as rent control, as well as the general post-war economic situation.

The political demand for improved housing was multifaceted and strong. The state of housing that soldiers returned to became a major point for the Prime Minister, David Lloyd George. One perceived threat was political stability in light of the nascent Bolshevik experiment. The idea was that improvement of living standards and decentralisation and suburbanisation of housing would reduce political risk.27 As Peter Hall writes, the scale of the increase in state provision from before the war was remarkable, and between ‘1919 and 1933–4, local authorities in Britain built 763,000 houses, some 31% of the total completions’.28 The urban character of these places as well as private, owner-occupied housing for the better off stemmed from the ideas of the garden city and suburb of Ebeneezer Howard, Raymond Unwin and his influential Nothing Gained by Overcrowding and the resulting Tudor Walters Report. The standards promoted, 64 including ‘terraces of no more than eight houses (which often led to culs-de-sac) and a density of twelve homes per acre’, were only plausible on cheaper rural lands.29

The march of planning continued through the interwar years as Britain adopted American/German-style zoning with the Town and Country Planning Act (1932), which ‘introduced “Planning Permission” into British legal history’.30 As Boys Smith rightly notes, the plans passed during this time – like zoning in much of the USA before the 1960s wave of reductions in allowed housing – were more than adequate for population growth even at the low densities stipulated. But there were peculiarities to UK planning. The past changes in the role of the state in housing represented an ever stricter rules-based system paired with increasingly active state provision, though later the regulatory system became the more discretionary one that has endured into the twenty- first century.

Up through the interwar period the pattern of economic activity had been primarily market-based. Transportation developments enabled middle-class movement to new suburbs, while government policies worked towards the same end for the working classes. But there was no comprehensive regional or urban planning. This changed in the aftermath of the Second World War. The new goals of post- war planning included regional economic planning and countryside protection. Regional planning sought not just to support declining regions but may have also cut the ground from beneath the most successful cities. This targeted not just London but also the Midlands.31 Changing economic forces and trade patterns weakened the once mighty northern industrial cities, while the south-east, due in part to 65 rising industrial fortunes in the areas around the North Circular in London and out west towards Slough, continued to grow. For some intellectuals, regional divergence and the swallowing up of countryside and fertile farmland – as well as increasing probability of another war – together cast a shadow over London’s buoyant prospects. As Peter Hall describes, the intellectual history of urban planning is intimately tied to economic ideas and the romance of dispersal in the form of regional economic planning. Such planning manifested itself as distribution of industry and commerce as well as of housing.32

A number of legislative Acts in response to the Barlow Report of 1940 dramatically changed the political economy of Britain. Not just the more famous Town and Country Planning Act (1947) and the New Towns Act (1946) but also the Distribution of Industry Act (1945) created a system whereby an entire category of decisions moved from the market to planning experts. With the 1945 Act, the government required industrial development certificates from the Board of Trade for new factories or extensions over a certain size.33 A similar control was later applied to office space. The purpose of the first two Acts mentioned was to alter the political economy of housing development dramatically. At a fundamental level the right to develop land was nationalised with the Town and Country Planning Act, which also made it easier for local authorities to designate green belts as part of their development plans. Any development incurred a 100 per cent betterment levy, though this was dropped. With the New Towns Act the hope was to start dispersing the population of inner London into planned low-density towns.

In addition to these changes, as well as bomb damage, millions of houses in old neighbourhoods vanished in slum-clearance efforts, many replaced by council housing. Over time, especially in London and other cities, this came to consist of towers that residents disliked compared to other types of housing, and which achieved lower densities due to the vast open spaces around them. Furthermore, costs associated with added floors increased non-linearly, so they were more expensive than other types of more popular, denser housing.

The result of these policies and of changes in the British economy over the last decades has been to force development in the most productive places in the UK farther out (when it is allowed by the discretionary planning system) and to prevent the intensification of existing neighbourhoods (except for notable quasi-public regeneration projects in the last few decades). Importantly, the economic result of this is twofold: first, productivity improvements that do occur increase nearby land prices; second, productivity itself is limited because the extent of the labour market is constrained by land-use regulations.

When workers in a location become more productive they produce more output for given inputs. It is this productivity that drives economic outcomes. In the abstract, the expected responses to productivity effects are manifold. First, employers will want to locate in more productive places. Second, employees will be drawn to them because they can pay higher wages. The result is that productive places will become denser with workers and locations near them more populous. An example from the USA is Willesden, North Dakota, where fracking led to a boomtown in the last decade. In the short run, when the supply of housing is fixed (it takes time to build), the price would probably be expected to rise – a relatively small number of existing units are being competed for by productive and therefore well-paid workers. However, in the long run the market would be expected to determine the price of housing – not just ability to pay but capacity of sellers to provide. Just as in any other market, the lure of profit draws investors to finance and build because sale prices exceed land and construction costs. If, however, the supply of housing is entirely fixed by regulation, all gains in productivity will accrue to existing landowners.

While the actual situation is not that dire, interventions that limit the ability of housing supply to respond to price signals – that is, limit its elasticity – sap the real benefits of productivity. Rather than just being a distributional question about how policy changes the beneficiaries of enhanced productivity, policy also creates deadweight loss whereby the total wealth of society is reduced. By limiting the supply response, fewer people move to productive places, with dynamic effects on productivity itself. In a world with fewer regulations limiting housing, the resulting increase in labour in productive places would increase the wealth of both individuals and the nation as a whole.

(This is Chapter 3 of Private Planning and the Great Estates (2023) split into five web-friendly sections)

See: Introduction, Chapter 1, Chapter 2, Conclusion

Peter Hall, Cities of Tomorrow: An Intellectual History of Urban Planning and Design in the Twentieth Century (Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 1988), p. 79.

Nicholas Boys Smith, ‘More Good Homes’ (London: Legatum Institute and Create Streets, 2018), p. 56; https://www.createstreets.com/wp-content/ uploads/2018/11/MoreGoodHomes-Nov-2018.pdf

Boys Smith, ‘More Good Homes’, p. 57, drawing on Norman Brett-James, The Growth of Stuart London (London: London and Middlesex Archaeological Society, 1935), p. 304.

Michael Hebbert, London: More by Fortune than Design (Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, 1998), pp. 23–6.

Referred to as ‘sorts’ in 1666–7 and later as ‘rates’; see https://www.british- history.ac.uk/statutes-realm/vol5/pp603-612#h3-0007

John Summerson, Georgian London (New Haven, CT and London: Yale University Press, 1945), pp. 53–4

Summerson, Georgian London, pp. 123–7

Summerson, Georgian London, p. 124.

Summerson, Georgian London, p. 125.

Summerson, Georgian London, p. 125.

Roger Harper, Victorian Building Regulations: Summary Tables of the Principal English Building Acts and Model By-Laws 1840–1914 (London and New York: Mansell, 1985).

Richard Dennis, ‘“Babylonian Flats” in Victorian and Edwardian London’, The London Journal 33:3 (November 2008), pp. 233–47; https:// doi:10.1179/174963208X347709.

Boys Smith, ‘More Good Homes’, p. 61.

Donald J. Olsen, The City as a Work of Art: London, Paris, Vienna (New Haven, CT and London: Yale University Press, 1986), p. 179.

Richard Dennis, ‘The Geography of Victorian Values: Philanthropic Housing in London, 1840–1900’, Journal of Historical Geography 15:1 (January 1989), pp. 40–54; https://doi:10.1016/S0305-7488(89)80063-5.

Peter Hall and Mark Tewdwr-Jones, Urban and Regional Planning (London: Routledge, 1975), p. 16

Richard Dennis, ‘Modern London’, in The Cambridge Urban History of Britain: Volume 3: 1840–1950, ed. Martin Daunton (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), p. 113

Simon Jenkins, Landlords to London: The Story of a Capital and its Growth (London: Constable, 1975), p. 185.

Boys Smith, ‘More Good Homes’, p. 59.

A. Yelling, ‘Land, Property and Planning’, in The Cambridge Urban History of Britain: Volume 3: 1840–1950, ed. Martin Daunton (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), p. 478.

Andrew Saint, London 1870-1914: A City at its Zenith (London: Lund Humphries, 2021), pp. 82–3; Dennis, ‘Modern London’, p. 33.

Boys Smith, ‘More Good Homes’, p. 62.

Dennis, ‘Modern London’, pp. 112–14.

J. A. Yelling, ‘L. C. C. Slum Clearance Policies, 1889-1907’, Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 7:3 (1982), p. 292; https://doi:10.2307/621992

Simon T. Abernethy, ‘Opening up the Suburbs: Workmen’s Trains in London 1860–1914’, Urban History 42:1 (February 2015), pp. 70–8; https://doi:10.1017/ S0963926814000479.

Dennis, ‘Modern London’, p. 114.

Hall, Cities of Tomorrow, p. 73.

Hall, Cities of Tomorrow, p. 76.

Boys Smith, ‘More Good Homes’, p. 62.

Boys Smith, ‘More Good Homes’, p. 62

John Myers, ‘The Plot against Mercia’, UnHerd, September 2020; https:// unherd.com/2020/09/the-plot-against-mercia.

Hall, Cities of Tomorrow, pp. 83–8.

Hall and Tewdwr-Jones, Urban and Regional Planning, p. 67.

(This is Chapter 2 of Private Planning and the Great Estates (2023) split into five web-friendly sections)

See: Introduction, Chapter 1, Chapter 3, Conclusion

London’s expansion was neither uniform nor managed:

London was expanding in the 1870s hand over fist, or rather in fits and starts. How was all that growth managed? Of planning in the modern sense of the word there was none to speak of, either physical or economic. London was still strictly laissez-faire; it had no extension or reconstruction plan of the kind that was starting to be favoured by or imposed upon continental cities. There was no active model of forethought for expanding the world’s biggest city, only an accumulation of passive constraints: building regulations, sanitary by-laws and covenants imposed by landlords.1

In the context of the early twenty-first century it may be the dynamism rather than the mix of grandeur and grime that stands out most about nineteenth- and early twentieth-century inner London. While we may mourn the loss of Georgian or even Victorian London, the ability of past generations to build anew is staggering. It is perhaps because of post-war destruction and the consequent development of the conservation movement that new development has become so difficult. While the conservation movement is, of course, much older, its scale and power changed after the Second World War with the Town and Country Planning Act (1947) and the Civic Amenities Act (1967). Among other things, the former introduced a listing system for historic buildings, the latter the concept of conservation areas rather than specific buildings, allowing neighbourhoods to be protected. Similar efforts were made in the USA.2

New replacing old often emphasises grand destructions of civic or quasi-civic buildings or government-aided destruction and ‘renewal’. Firmly in the pantheon of conservationists’ anathema are: the destruction of Euston Station and the threat to St Pancras (and, in the USA, demolition of Manhattan’s Penn Station); the building of great highways dividing neighbourhoods;3 the destruction of neighbourhoods themselves through slum clearance. Widespread demand for historic preservation laws is relatively new – the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings was only founded in the late nineteenth century. The Georgians, Victorians and Edwardians remade their cities with relatively little concern. Many buildings in Manhattan or central London replaced existing ones, including some whose loss shocked later generations. This was less the case away from city centres. The technological changes of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries allowed cities to expand, so that generally the greater the distance from central London the newer the houses, most of which stand on former farmland.

Even before conservation rules, many areas on the great estates were kept intact, although others were systematically rebuilt after their initial building lease or later repairing leases expired. As land prices increased, many of the vast London seats of the aristocracy were demolished or adapted for other uses. In New York, the mansions of the gilded age met the same fate.

Perhaps the most important advantage of the great estates, as opposed to smaller freehold landholding, was that their size and the nature of reversionary leases gave them incentive and capacity for private planning. They could undertake comprehensive replanning and rebuilding. Many buildings in current conservation areas, such as the Queen Anne revival red-brick streets of the Grosvenor’s Mayfair estate and the Cadogan estate, are themselves replacements. Furthermore, even when not comprehensively rebuilt, Georgian streets were transformed through the application of ornamentation and terracotta tiling. The leasehold system allowed such changes at street, block or even wider level. The great estates could take advantage of economies of scale more easily – and do far more – than individual freeholders, and could reduce negative spillovers in a way that involved neither the direct incentive of freeholders nor the limited regulatory system. This capacity was, of course, constrained, and depended – as with public planning – on geography, features of the markets and even some degree of unforeseen good fortune.

As such, the system offered some of the benefits of both widely dispersed freeholds and later government controls. During the long period of the initial building lease – and any subsequent leases – the power of the estate was mostly limited to enforcing the restrictions set out in covenants. While rebuilding freehold land was more straightforward in this period before planning, the results were often less pleasing aesthetically than more uniform estate rebuilding. Other aspects of private planning, such as coordinating land use, were also more easily practised by the estates.

This chapter shows how in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries the great estates responded to changes in the market. While they became wealthier as land values rose, this also led to their densifying holdings. It shows how this took place in different ways over time and within the economic, technological and social context that drove the market. The leasehold system allowed both regulatory control and market incentives. In response to market forces, great estates used leases to densify existing neighbourhoods incrementally with additional storeys and flats, updated architectural designs to changing tastes and sometimes comprehensively rebuilt areas.

It is nigh impossible to exaggerate the scale of urban change in the nineteenth century. For seven decades the average ten-year growth rate for the population of London varied between a low of 16 per cent and a high of 21 per cent.4 With figures like this the population grew from around 1m in 1800 to 6.5m by 1900.5 Indicative of the scale of growth is that roughly half those living in London in 1851 were not born there.6 It was not the scale alone that led to changes but also the form it took, enabled by new technologies.

In the first few decades of the early nineteenth century this growth, like all prior urban growth, was concentrated in the emerging city centres. Walking-speed provided a limit to the geographic spread of urban areas. Transportation advances over the century – railways, the underground and the shorter-range feeder transportation of omnibuses that allowed people to commute from their home to a station – enabled the extensive growth that pushed ever outwards. London quickly outgrew the confines of the City, filling in along the Thames towards Westminster before 1800, but it was really in the nineteenth century that it began swallowing up increasingly remote villages. Fashionable London shifted westward to surround Hyde Park rather than just abut its eastern side: Bayswater, Kensington, South Kensington, Knightsbridge and Belgravia joined earlier Mayfair to complete the rectangle around the park. In the process described in Part II, the architect Samuel Pepys Cockerell laid out Tyburnia on the Bishop of London’s lands near Paddington to the north-east of the park. In Belgravia, Thomas Cubitt did the same on the Grosvenor land. To the north, the efforts of John Nash and the master builders James and Decimus Burton pushed into Regent’s Park. And later the efforts of other private developers, small and large, increasingly turned agricultural land near London into suburban land.

Outside this ring the wealthier, who could afford the commute and wanted to escape the increasingly polluted core, moved to areas such as Clapham, Richmond and Hampstead7 and commuted by private carriage. Even before the advent and expansion of railways, horsedrawn omnibuses allowed those who could not afford a private coach to commute from greater distances. And for places out on the river, steamboats began running along the Thames in the early nineteenth century. With the coming of the railways the commutable area of London expanded dramatically. Though the countryside grew ever more physically remote as fields were filled in, railways allowed easier travel. Towns such as Brighton became not just holiday destinations for Londoners but far-flung suburbs. Such development at lower density absorbed more countryside around cities than was common on the Continent, but gave more people private gardens.

With this transport revolution alone, much of the farmland around London and the industrial cities of the north would have been converted to housing as the returns from building terraces rose above that of growing crops, but this was reinforced in the later nineteenth century by a dramatic fall in agricultural prices. This had a profound impact on the landed aristocracy, including some of those fortunate enough to have London estates. Within just 50 years the value of urban land and houses grew dramatically while that of agricultural land plummeted:

In 1850–1 land had been assessed at £42.8m in England and Wales and houses [including the land on which they stood] at £39.4m. By 1900–1 the figures were respectively £37.2m and £157.1m, reflecting urbanisation and agricultural depression.8

Thus agricultural depression and increase in commutable distances led to more and more of the countryside joining the commuter belt. Centripetal forces drew outsiders to the cities but centrifugal forces drew those who could afford the fares out towards the edge. Furthermore, workmen’s fares allowed cheaper commutes and therefore enabled more suburbanisation.9

The spread of the speculative builders enabled by the transport revolution is underemphasised in narratives of the creation of modern Britain. The scale of urbanisation and suburbanisation, in particular in London, was unprecedented. What may now appear quaint and sleepy suburbs of the sort popular in most developed countries were in fact innovatory and modern.

As Donald Olsen correctly stated: ‘the proliferation of scattered settlements [outside inner London] was a more significant portent than the development of terraces and squares … unprecedented in form and structure as well as astonishing in extent.’10 The nineteenthcentury spread of London was revolutionary and set the pattern later cities followed. Yet even while this extensive growth was occurring, land values in the centre were rising so much that taller and taller buildings were replacing existing ones, and open lands that survived within London were filled in.

These great changes were both caused by and the cause of sustained economic growth. People flocked to London; rail infrastructure was built and suburbs constructed to take advantage of the great productivity of the City of London and other commercial and industrial hubs. Agglomeration effects for these areas were bolstered by the improvements in technology that enabled more people to work together during the day while living outside these specialised districts. Estimates suggest that in the counterfactual without railways, London as a whole would have been over 50 per cent smaller.11

Importantly, the laying of railway lines led to a transformation of the City of London and the West End, as well as the surrounding countryside. Transport speed determines the effective commuting radius of commercial centres. The increase in speed – and decrease in price – meant that workers could commute greater distances, but this only increased the importance of floorspace in the centre. Suburbanites may have fled from them each evening but they spent most of their day in the City or West End:

As commuting costs fall, workers become able to separate their residence and workplace to take advantage of the high wages in places with high productivity relative to amenities (so that these locations specialize as workplaces) and the low cost of living in places with high amenities relative to productivity (so that these locations specialize as residences).12

As commercial users outbid residential users, these factors combined to transform the City into the central business district known today. Existing City residents could do well for themselves by vacating, for:

the rooms formerly used as living rooms are more valuable as offices, and a citizen may now live in a suburban villa or even in a Belgravian or Tyburnian mansion, upon the rent he obtains for the drawing-room floor of the house wherein his ancestors lived for generations.13

The night-time population plummeted while the daytime population rose. New purpose-built commercial offices began to replace older terraces. Similar forces would push westward in the twentieth century as increasing portions of the great estates, such as Bloomsbury and Mayfair, became commercialised.

By contrast, in those places with high amenity values the rising cost of land led to the densification of housing, not commercialisation. The historical novelty of increasingly distant suburbanisation and commercial specialisation in a central business district should not distract from the natural residential densification that was occurring in inner London. Some of the densest residential areas of the UK, often denser than the post-war council estates, are in the parts of inner London built and rebuilt by the great estates in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

In the context of this growth and innovation, the flexibility of the leasehold system enabled rational rebuilding when leases fell in; that is, when they expired and all rights over the property reverted to the landowner:

It was only when the leases had expired and the landlord was once again in actual possession of the buildings that he could adopt a dynamic policy of change and adaptation. He might then choose either to reassert or to abandon the original plan. If he decided on the former, he would grant new repairing leases. If the latter, he would demolish the buildings and grant new building leases for their sites. Legally he was a free agent, no longer limited by the rights of subordinate leasehold interests.14

The following focuses on the ability of the great estates to alter the appearance of neighbourhoods and make other incremental changes; the next section looks at more substantial rebuilding efforts.

Architectural taste is not immune to the temporary fads and fashions that afflict other arts. The houses on the great estates, like most residential buildings, were rarely designed by the most prominent architects. The architectural language often lagged behind fashion, though much of it retains appeal. In the era before conservation areas or architectural listing, many attractive and important buildings were demolished – even buildings by the great John Soane were not spared.

Estates responded to changing aesthetic taste in various ways. Some attempted to hold on to the existing designs; others added ornament to Georgian terraces so that stylistically they appeared more Italianate or Queen Anne. On the Bedford estate the changes of aesthetic taste away from the austerity of Georgian architecture – and the shift westward of the middle and upper classes – harmed the bottom line. Gower Street on the Bloomsbury estate or Harley Street on the Portland were touchstones for critics of Georgian architecture, much as the hulking modernist Trellick Tower in north-west London is for critics of brutalism. Towards the end of the nineteenth century, however, the Bedford estate began moving towards fashionable architectural taste by requiring new tenants to apply terracotta to existing terraced houses and, at the turn of the century, building two ornate hotels on Russell Square, one of which, the Russell, still stands.15

Whereas the Bedford was seen as hopelessly old-fashioned, the Cadogan and Grosvenor estates attempted to lead taste by commissioning prominent architects.16 The aesthetic reprofiling of a neighbourhood was sometimes the result of the architectural tastes of the great aristocrats or their surveyors, but often simply the product of commercial interest. On the Grosvenor’s Mayfair and the Cadogan estates, whole areas – such as Mount Street and Hans Town respectively – were rebuilt in contemporary fashion and to a higher density. On others it was not economic to rebuild more fully, so the response to the market was aesthetic tinkering and other smaller changes. Without delving into details it is worth noting that these often diverged from prevailing architectural taste. Builders kept building what looked like Georgian buildings far after professional taste soured on them. The estates quickly integrated into their designs the gothic revival favoured by architectural elites but used it for churches more than residential buildings, with a few exceptions in St John’s Wood, Holland Park and Islington. While the gothic revivalists pilloried painted stucco, estates and speculative builders continued to use it, albeit in Italianate not Regency styles, until the red-brick and terracotta styles of the later nineteenth century became more prominent.

Requirements to update buildings to changing circumstances did not stop at aesthetics – the renewal of leases sometimes required additions or internal renovations. Two forms this took were the addition of storeys and the renovation of mews – as working-class housing in addition to stabling. Examples of more substantial efforts are given in later sections.

It was common, as part of both renewal and new leases, for the estate as freeholder to require of lessees both aesthetic updating and the addition of storeys. Already, for instance, in the middle of the nineteenth century on the Grosvenor’s Mayfair estate:

The applicant had to sign a bond, often of over £1,000, to ensure the due performance of the works, which generally included the addition of a Doric open porch and sometimes a balustrade in front of the first-floor windows (both in Portland stone), cement dressings to the windows, and a blocking course, balustrade or moulded stone coping at the top. Sometimes an additional storey was to be built.17

In 1888, on the Portman estate, a similar requirement was imposed on ‘leaseholders wishing to renew in the more desirable properties’.18 Even earlier, on that estate, tenants were incentivised to add an additional storey through the practice of issuing 40-year leases rather than shorter ones.19

Over time the land costs of a stable and the ease of first hiring coaches and then riding on newer forms of transportation led to fewer mews being built on newly laid-out developments.20 Later this led to the conversion of stables into mews houses but at first the mews were mostly just modernised or replaced. At the smallest scale this could include adding housing above stables, such as for a married coachman and assistant; at the extreme, new residential buildings would be put up on mews streets.21 As the cost of running large houses increased, purpose-built small – sometimes called dwarf or bijou – houses were erected in mews and side streets behind taller houses, such as in Mayfair and on the Portland/Howard de Walden estate in Marylebone:

At about this time this process was taken a stage further by the occasional conversion of stables into dwelling houses, the first known example being at No. 2 Aldford Street in 1908; and in later years the size and quality of these equine palaces was such that many of them proved well suited for adaptation to domestic use for residents no longer able or willing to live in a great house in one of the fashionable streets.22

Throughout London, houses were divided as the price of land increased and potential residents were unable to afford a full terraced house. While often prevented by covenants aimed at maintaining the tenor of middle- and upper-class neighbourhoods, division was later sometimes achieved by estates on reversion. For instance, in Marylebone, Mayfair and Belgravia the changing circumstances of the neighbourhood led to deceptive continuity where lateral flats were built behind façades.23

As in the City, changing factors could result in higher values from commercial uses. As discussed in Part II, there was a consumer preference for the separation of uses, for which the most capable estates provided via covenants of use. However, both Bloomsbury and Mayfair commercialised in the late nineteenth century and even more so in the twentieth. Sometimes estates resisted, though ultimately they embraced commercialisation as the most valuable use of the land, while seeking to counter negative spillover effects by limiting the types of offices allowed.

Besides offices, estates increasingly encouraged shopping streets with purpose-built storefronts to replace the ground-floor shops in converted terraces. Armed with plate-glass windows, shops could now appeal far more. Increasingly attractive commercial streets – such as Woburn Walk, built in the early 1820s by Cubitt on the Bedford estate – led the way for later enclosed arcades.24 Older portions of estates mimicked these designs when leases came up, improving and consolidating shops in areas or streets (e.g. Mount Street on the Grosvenor estate).

Just as in the original development, redevelopment would allow estates to assess the provision of green space. In Mayfair, for instance, the creation Mount Street Gardens and Brown Hart Gardens provided open-access greenspace. Furthermore, as with earlier garden squares, estates built restricted-access green space in the form of communal gardens.

As traffic and noise increased in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, internal communal gardens surrounded by buildings were preferred to garden squares. The Ladbroke estate built two such in Notting Hill, but interestingly the Grosvenor created two much smaller ones – Green Street Gardens and South Street Gardens – in the early twentieth-century redevelopment of Mayfair. By redeveloping blocks and creating internal communal gardens on land previously devoted to stables and garages, the estate increased the ground rent it could charge.25

One benefit of estates’ rebuilding when leases fell in was that whole neighbourhoods could be treated comprehensively: ‘A freeholder of an individual building could at best try to adapt it to the changing character of the neighbourhood. A large landowner could change the character of the neighbourhood itself.’26 Nearly the whole of contemporary Mayfair, Knightsbridge and Chelsea is the product of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, despite being originally developed in the eighteenth. This rebuilding was facilitated by the expiration of building leases (often of 99 years), but did not always occur purely by chance or as an inherent product of the leasehold system. Rather, over the nineteenth century, as the price of land rose, the benefits of widespread redevelopment increased and estates took action to coordinate leases to maximise their power to adapt to changing conditions. Even on the wealthy Grosvenor estate, the Second Marquess of Westminster was initially limited in his actions ‘as hitherto virtually no attempt had been made to make the leases of adjoining sites expire simultaneously’.27 He did not repeat the mistakes of his father, and with costly and time-consuming efforts he and his staff ensured that renewal leases on neighbouring properties were strategically structured to come due at the same time and thus ‘phase the rebuilding of large parts of the estate over a number of years’.28

Such estates were not representative, merely the most successful and consequently having the highest land values, wealth and power. The point is not that all estates engaged as they did, rather that this institutional framework led to densification in the most successful areas. This kind of strategic behaviour – not to mention the rebuilding itself – was costly but ultimately profitable, with benefits for the estate, residents and everyday Londoners.