Exploring a Christian perspective on contemporary issues of political economy

There are growing concerns that capitalism and democracy are in crisis. Despite the success of free markets in creating global prosperity over two centuries, the recent slowdown in growth in Western economies, the persistence of inflation, increasing economic inequality, financial instability and the explosion in debt have called into question the value of market capitalism. Moreover, trust has been eroded in liberal democracies because of dysfunctional governments, a perceived lack of commitment to truth and political leaders playing the game to the edge of legality. Added to these concerns are the growth of a post-modernist culture with steadily increasing social fragmentation, divisiveness and the lack of a unifying and accepted source of appeal.

We are living in the 21st century in Western societies in which religion has not just been replaced by secularism, but the one God of the Christian religion, with its deep roots in Judaism, has been replaced by the pluralism of the many gods of modernity. As a society we require those in leadership and authority in business and politics to have a moral compass and as Adam Smith set out regarding the virtue of prudence and Burke regarding the role of religion, our fellow citizens need values of honesty and sympathy if we are to seek the common good.

Against this background and under the auspices of the Centre we have decided to launch a series of colloquia in which to explore a Christian perspective on contemporary issues of political economy. On each occasion a small panel of experts will present their thoughts on the chosen topic, and other participants will then have the opportunity to make their own contributions to a free-flowing discussion. Participants will be invited from across the political spectrum and the number kept to around twenty. Following the links below you will find the contributions made to each meeting. We hope you find the papers stimulating.

Senior Research Fellow, Centre for Enterprise, Markets and Ethics

Our third Fforestfach Colloquium took place in the House of Lords on the morning of Thursday, 30th January 2025, on the topic of Postliberal Political Economy, and brought together three speakers from academic, political, economic and media backgrounds.

Liberalism enjoyed a renaissance in the second half of the twentieth century. At the beginning of the 1960s, we saw the development of a socio-cultural liberalism on the left of UK politics, while in the 1980s, we experienced a growing economic liberalism from the right. Both those trends have given rise in the present century to the growth of post-liberalism, as explored in publications such as The Politics of Virtue (2016) by Adrian Pabst and John Milbank and Postliberal Politics (2021) by Adrian Pabst.

These publications, among others, provide a blueprint for a national, communitarian renewal, emerging from both the centre-left and centre-right. Importantly, postliberalism recognises the importance of the Christian heritage and Judeo-Christian ethics in providing a foundation for the renewal of a civic covenant, in the form of a partnership between generations and regions, and with nature.

At our Colloquium, we were addressed first by Professor Adrian Pabst of the University of Kent, who is also the Deputy Director of the National Institute for Social Research. His contribution pointed to the recurring crises experienced in advanced capitalist economies such as the UK, Germany, France, Italy, and Japan, which have struggled with low growth, high inflation and stagnant real wages ever since the 2008-09 financial crisis. Professor Pabst argued for a shift towards a social market economy, anchored in a greater sense of purpose and virtue.

He was followed by two distinguished speakers, his co-author, Dr John Milbank, Professor Emeritus at the University of Nottingham, and Miriam Cates, the former Conservative MP for Penistone and Stocksbridge in Yorkshire. They discussed alternative approaches to the postliberal economic challenges of our time, with Dr Milbank exploring the historical relationship between Christianity and Political Economy, suggesting that a truly Christian approach would seek to marry up what is practical and useful in modern economics with a more ancient humanism that does not surrender its ethical values. Miriam Cates, on the other hand, argued that many of the socio-economic crises we have experienced arise from the breakdown of Christian family values in the postliberal era, and called for a political economy based on a foundation of pro-family policies and a welfare state that encourages and supports families as a building block for a modern human society.

The second Fforestfach Colloquium took place in the House of Lords on Monday 29th April. We were privileged to welcome as our lead speaker an eminent professor from Harvard University, Professor Benjamin M. Friedman, who is the William Joseph Maier Professor of Political Economy and the former Chairman of the Department of Economics. Professor Friedman’s newest book, published in January 2021, is Religion and the Rise of Capitalism, and we invited Mr Friedman to speak to our invited audience about the theme of his book, to be followed by two highly-respected commentators, Professor Emeritus Forrest Capie of the Bayes Business School, and Lord (Mervyn) King of Lothbury, former Governor of the Bank of England.

Centre for Enterprise, Markets and Ethics

A recent article reports on work by researchers at Anthropic, the AI lab that developed a ‘reasoning’ AI model, and their ability to look into the digital brains of large language models. Investigating what happens in a neural network as an AI model ‘thinks’, they uncovered some unexpected complexity that would suggest that on some level, an LLM might have a grasp of broad concepts and does not simply engage in pattern matching. Conversely, there is evidence to suggest that when a reasoning AI explains how it has reached a conclusion, its account of how it has reasoned does not necessarily match what the ‘digital microscope’ suggests has gone on. Moreover, sometimes, an AI will simply produce random numbers in response to a mathematical problem that it can’t solve, and then move on. On occasion, it will respond to a leading question with reasoning that leads to the suggested conclusion, even if that conclusion is false. Thus, it seems, the AI will appear to convince itself (or the human interlocutor) that it has reasoned its way to a conclusion when in fact it has not.

The Human Foibles of AI

Should we consider this to be indicative of an approach towards human levels of intelligence or reasoning? After all, even the failings of AI are similar to our own. Most people have given up on a problem as being too difficult at some point in their lives, perhaps giving an inadequate account of their efforts to deal with it. Almost all of us, as school children, will have guessed at the answers to the questions in our maths books and shown some kind of working-out, even if we didn’t have any real confidence in what we had written. Similarly, if asked a difficult question in class, most of us will have attempted to give an answer that consisted of little more than repeating back to the teacher partial information – provided by the teacher in the first place and which we had not understood – in the hope of convincing him or her that we knew what we were talking about.

Perhaps, then, advanced AI models are closer to human beings than we have been willing to accept. If this is the case, where does the difference between AI reasoning and human reasoning lie? Or, rather, on what grounds can we say that human beings reason or think, while machines, however sophisticated, do not? What does it really mean to talk about computers ‘knowing’, ‘remembering’ or ‘working things out’?

Knowing That / Knowing How

There is a distinction to be drawn between conscious, propositional knowledge, and skill or aptitude – between ‘knowledge that’ and ‘knowledge how’. The former is a grasp of a matter of truth and can be held before the mind; the latter is something we are able to do and can often be executed with little thought. It is with this distinction in mind that we can easily agree with the philosopher and essayist Michel de Montaigne, who argued in his long essay An Apology for Raimond Sebond (1576), that if human beings can have knowledge, then animals surely can, too. When we look at the feats of which they are capable, beyond anything that human beings can manage without complex machinery and intricate calculations, how can we claim that they do not ‘know’? Surely a blackbird knows how to build a nest and a bumblebee knows when to hibernate? A spider’s web is a beautiful and intricate construction that any human being would struggle to build. Their levels of consciousness and their powers of reasoning are far below ours, yet in some sense they ‘know’ what they are doing (even if, we might claim that they do not know why or to what purpose – as a hamster probably does not have a long-term end in view when she hoards food and various other objects). If we think of the difference between the flight of a blackbird and what human beings have managed with aeroplanes and helicopters, the former is a natural aptitude, devoid of reason or thought, while the latter, cumbersome (yet ingenious) as it is, is based on vast array of theory, calculation and applied propositional knowledge.

Knowledge, Reason and Meaning

The distinction between knowledge how and knowledge that is not straightforward: there are various things we might know that might not cleanly fit into one category or the other – such as the knowledge that one is loved by one’s mother. There are also different ways of arriving at knowledge, some highly complex and based on extensive calculation, while others are simply intuitive. Similarly, there are different grades of reasoning, from basic connections of cause and effect or means and end, to highly abstruse relations between concepts. Nevertheless, when we ascribe to AI models the ability to reason or to know, we typically have in mind knowledge of the propositional variety: the AI model uncovers a fact or conclusion about some state of affairs, or provides an account of an expedient methods for achieving some goal, by way of a chain of steps.

Leaving aside the question of the extent to which animals possess such knowledge, we might say that in order to truly constitute knowledge, propositional knowledge requires the ability to understand. That is to say, for a human being to know, he or she must understand what is known, and where reasoning is involved, he or she must have a grasp of why the conclusion reached is valid. Moreover, he or she should understand what that piece of knowledge means in connection with other knowledge possessed, as part of a world filled with knowledge and meaning.

The Capacity of AI in the Absence of Consciousness

To illustrate this, we could point to the difference between solving a problem by understanding the nature of the problem itself, knowing the correct method for addressing it and understanding why the answer is right, and applying a process by conjecture, blindly following it and reaching a solution that might – or might not – be correct. Arguably the latter is still a form of reasoning, but a greatly diminished one. Even where the correct method is invariably applied and the solutions are always correct, the result surely does not constitute knowledge. In the absence of consciousness, these are the highest forms of reasoning and knowledge that AI can possess. When we say that a machine has reasoned or that it knows, we can really mean no more than this.

AI models can be incredibly efficient, solving problems and processing data more quickly than any human mind can manage; they can contribute to our knowledge and lead to hugely beneficial material improvements. For artificial intelligence, however, no matter how sophisticated and even when accompanied by an account of how a solution was reached, there is no knowledge or reasoning in the full, human sense. While a machine can disclose that the sun rose at 5:50 yesterday and can calculate the time of sunrise on any given date in the future, it cannot be said to know the time of sunrise. Between human beings and the most ingenious artificial intelligence, there remains the gulf of consciousness and the grasp of meaning that it renders possible. This might remain the case forever, but as machines approach more closely to human levels of intelligence, perhaps they will enable us to understand ourselves better and some of our own cognitive capacities.

Image: Designed by Freepik

Neil Jordan is Senior Editor at the Centre for Enterprise, Markets and Ethics. For more information about Neil please click here.

The Centre for Enterprise, Markets and Ethics (CEME) was pleased to host a roundtable event on the topic of non-executive directors.

The full report is available to download here.

The role of the non-executive director is essential to the proper functioning of corporate governance. The expectations on directors have been tested by corporate scandal. What are the reasonable expectations that society places on those that undertake this task and what are the appropriate legal responsibilities?

The event was chaired by Richard Turnbull and our main speaker was John Wood, Lecturer in Company and Insolvency Law at Lancaster University’s School of Law. He has a particular interest in the law around the duties of directors and has published numerous articles and several books.

This event took place on Thursday, 12th December in the Council Room at One Great George Street, London SW1P 3AA.

From April 1st this year, local authorities in England have the power, under the Levelling Up and Regeneration Act 2023, to charge a Council Tax Premium of 100% on second homes. Many councils have availed themselves of the opportunity.

The Justification

The move to charge a premium is driven by a number of concerns about public services and the cost and availability of housing. It has been suggested that the council tax premium will provide additional funding for public services. In addition, some argue that by attaching a premium to a second property, councils are in effect discouraging second home ownership with a view to making more houses available for local people to buy, who, it is claimed, have been ‘priced out’ of the market in the areas in which they have grown up and which they work, owing to the inflated prices occasioned by the purchase of second homes by wealthier buyers.

The Opposition

Against the new measures, many have argued that charging a premium on properties, the owners of which are absent for some – or much – of the year and who therefore do not use local public services to the same extent as full-time residents, is simply unjust. Others contend that by letting their properties to holiday-makers, second home owners are encouraging local tourism which brings money into regional economy, a proportion of which will, of course, find its way to the council in taxation.

In addition, it is argued, such measures, if they do deter second home ownership, will do little to provide additional housing stock, particularly in popular tourist areas, because second homes, often being character or luxury properties, are not typically the kinds of houses that are within the reach of many local buyers – particularly first-time buyers. Thus, buying such properties as second homes is not the cause of high house prices in the area; rather, the problem is the result of insufficient availability of housing more generally, which ought to be addressed by local development plans. Some even suggest that since not all second homes are habitable and often require considerable renovation at the owners’ expense, ultimately those buying second homes are adding to the stock of available housing. After all, they are unlikely to own the property forever and when it is sold in the future, a previously derelict building will be returned to the market as a useable home.

A Sumptuary Law?

The use of such premiums invites comparison with the sumptuary laws found throughout history, such as those of the Roman Republic and the imperial period which restricted spending on feasts or women’s jewellery. Such laws were usually aimed at deterring – or at least registering disapproval of –the indulgence in luxuries considered contrary to good morals, though in their attempts to limit displays of wealth by the upper orders, it is also likely that on occasion, their purpose was also to temper the resentment of the poor. One might see certain similarities with council tax premiums attached to second homes and wonder whether they will do less to address any real problems surrounding housing or public services than to express disapproval.

Difficulties and Assessments

Sumptuary laws have not proved easy to enforce and have frequently been avoided by their intended targets. More significantly, they often have unforeseen consequences, as a recent example from China shows. When, in 2012-13, the President launched a drive to cut back on lavish spending and tackle corruption, over 50 hotels soon sought to drop their five-star ratings in order to survive because local government officials could no longer stay in luxury hotels. One tourism group saw a fall in revenue of 18 per cent at its hotels, business declined at many private clubs and restaurants and luxury brands witnessed significant declines in sales (around 30% in one case) – yet many of the rich and powerful were able to move and conceal their wealth using offshore holdings (both legitimate and questionable).

Sumptuary laws are not only difficult to enforce: they are also complicated to assess. By what standard are we to measure whether they have achieved their objectives? Where they are aimed at preventing excess and restoring traditional virtues, which particular moral standard or virtue are we to identify as being the target of the legislation, and how are we to establish whether it has been successfully defended or re-established? The most likely concrete measure would consist of statistics indicating a satisfactory number of successful prosecutions for breaches of such laws, but these do not in themselves demonstrate an improvement in morals or restored personal virtue. Citizens are more likely simply to have kept the manifestations of vice sufficiently private, with no reduction in excess.

Similarities and Differences

Similar difficulties arise with regard to council tax premiums. In the first instance, there are suggestions that the premiums will simply be avoided, such that the charges will frequently miss their targets. For example where a second home is let for a certain proportion of the year – as is often the case with properties that also serve as holiday lets – owners might be able to register for business rates rather than council tax. In such circumstances, it has been claimed, local authorities might actually suffer a decline in council tax revenue.

How will their success (or otherwise) be ascertained? This is likely to be a subject of disagreement, but based on the justification for their introduction, measures of success for council tax premiums would surely include better-funding for (and perhaps improvements in) public services and, perhaps more significantly, greater availability of housing for local residents in a particular area, or at least lower prices. Doubtless there will be debates surrounding the interpretation of data when it emerges, but advocates and critics of the new measures are likely to look carefully for evidence of both in the coming years.

The major question that must be addressed when seeking to establish whether the council tax premium is a modern sumptuary law, is how it bears on morality. The laws of the past were often concerned at a decline in traditional virtue. Leaving aside the question of whether it is for governments to determine and enforce morality, which virtue, which ethical principle, which moral law has been breached by those who have invested their earnings in a second home? If none can be identified, then in the absence of evidence establishing their success in policy terms, council tax premiums will be increasingly hard to justify.

Neil Jordan is Senior Editor at the Centre for Enterprise, Markets and Ethics. For more information about Neil please click here.

The Centre for Enterprise, Markets and Ethics (CEME) is pleased to announce the publication of a report on the topic of non-executive directors.

Is the Non-executive Director worth saving? by Richard Turnbull is available to download in PDF format here.

Of growing popularity at present is the phenomenon of the ‘mystery box’: a box or case purchased – usually from an online provider – that contains various ‘unknown’ objects. A fairly typical example would cost somewhere in the region of £90 and will be described by the seller as either unclaimed luggage from an airport or a collection of items including lost deliveries or goods returned to online retailers. Numerous questions can be raised with regard to the supply of the contents. We might wonder how these goods came to be lost in the first place and were never returned to or reclaimed by the original sellers or travellers, but have somehow made their way to online vendors. There are, however, interesting and salient considerations regarding the consumption of such boxes – the demand side of the equation, as it were. Is there anything unique or unusual about the market for mystery boxes and people’s engagement with them? And is its emergence indicative of any social or cultural trends?

Gambling and Games of Chance

There are certain features common to buying a mystery box and forms of gambling: the purchaser parts with money in the hope of a decent return, but there is also the prospect of loss. When the box arrives, it might contain something far more valuable than the outlay, such as a new laptop, but equally might contain something that the buyer will consider useless, such as some ill-fitting footwear and a damaged photograph frame. There are therefore elements of risk and luck involved, which might go some way towards explaining the growing popularity of mystery boxes. However, since there are no stated or calculated odds to inform the buyer’s decision, the comparison with conventional forms of gambling is limited. The absence of any clear element of play also puts strain on the idea that buying a mystery box is akin to well-known, small-scale games of chance, like hook-a-duck or a tombola. In spite of the similarities with gambling therefore, the transaction remains a purchase. That is to say, the buyer parts with money and expects to receive goods, even if he or she does not know what those goods will be. Moreover, the fact that the transaction is a purchase and not a bet in the usual sense is reinforced by the experience of disappointment frequently reported by buyers and their willingness to complain about the goods that they receive – a response that would be out-of-place in a casino or at a village fete.

The Experience Economy

Perhaps a more fruitful approach to making sense of the phenomenon of the mystery box would be to understand it as part of the experience economy. Reports indicate a shift among consumers towards the purchase of an experience rather than some concrete good – hence the growing importance of attending gigs over buying downloads of music. There is an increasing prevalence of themed evenings in the hospitality sector and a growing trend among some readers to visit a bookshop and pay for a book wrapped in brown paper, presumably with a view to being exposed to a kind of literature that they might not normally choose. In this light, the mystery box can be interpreted as the purchase of a certain type of experience involving uncertainty and excitement – an understanding that makes more sense when we consider that buyers will often upload to social media an ‘unboxing’ video when their purchase arrives. Thus, the mystery box purchase becomes a shared experience, additionally attracting followers to a social media channel, which itself potentially brings various emotional and often pecuniary rewards for the buyer (though it is unclear whether the financial return for attracting ‘views’ would cover the cost of the box itself). Nevertheless, we are still faced with the fact of disappointment. When customers buy experiences such as a bungee jump or a climb over the O2 Arena, there is an expectation of a certain quality or level of experience, commensurable with the price. Unlike mystery boxes, people do not make these purchases with the expectation that they might well be disappointed. Part of the appeal of a mystery box is doubtless lies in the ‘experience’ but it is not clear that the phenomenon is simply reducible to this.

Consumption, Desire and Catholic Thought

The philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer described boredom as a situation in which the pressure of the will remains but has no object towards which it can be directed – hence the prevalence of card games and habits such as smoking, as humanity devises means of passing time which is felt to be a burden. Schopenhauer’s famously pessimistic account of human existence was based on a very particular metaphysics but his account of boredom, by which we are led to ‘go in quest of society, diversion, amusement, luxury of every sort, which lead many to extravagance and misery’ might inform our understanding of the market for mystery boxes. Rather than having its explanation in a will that has no object, perhaps buying a mystery box is suggestive of an urge to consume, only without a clearly desired object. Thus, the act of buying itself becomes the object and in this, the purchase differs from normal transactions. However, when the goods arrive and prove not to have been worth the outlay, the usual norms of purchasing reassert themselves and the buyer feels disappointed.

If this is indeed what is going on – at least in part – then Catholic thought has something to contribute and might offer an analysis in terms of ‘disordered concupiscence’ or cupidity. Human beings have an array of natural and necessary desires, such as for life or food, but desires often extend beyond our needs and will reach for wealth, fashion or fame. Such ‘non-natural’ desires are potentially infinite and can run out of control. When unrestrained and no longer subordinate to reason, which aims at the good of the whole person, these appetites can affect our judgement, leading us to excess, intemperance and a focus on gratification, rather than the pursuit of a life of flourishing, informed by a correct understanding of goods and their relative importance in life. In short, we are lured away from our ultimate purpose.

No single account is able to explain entirely the emergence of the market for mystery boxes. Buyers are likely to be driven by different motives, but it seems clear that there are elements of risk, the hope of rewards beyond the outlay, the enjoyment of the experience itself and the potential to share this with others via social media. Importantly, the purchase – unconventional as it is – remains a purchase. The moral question arises when we consider the possible end or source of such transactions.

Image: Designed by Freepik (www.freepik.com)

Neil Jordan is Senior Editor at the Centre for Enterprise, Markets and Ethics. For more information about Neil please click here.

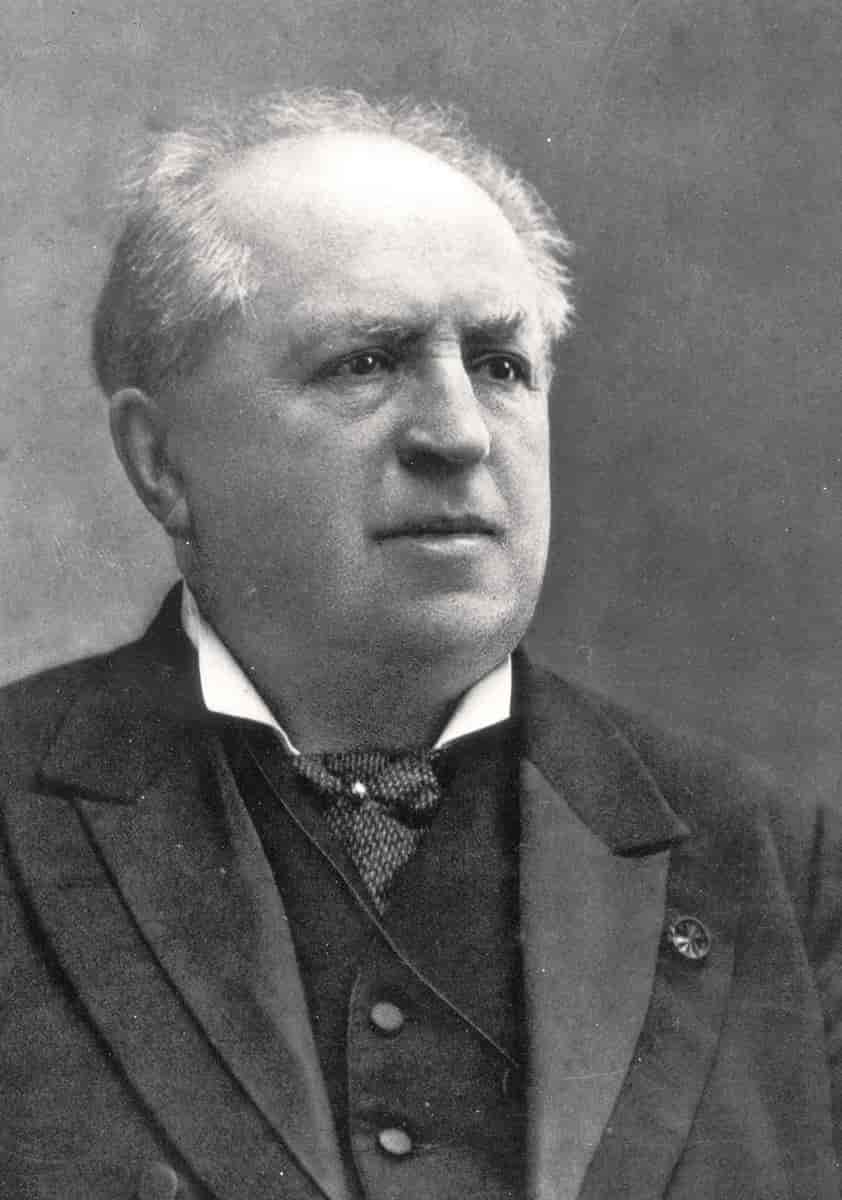

Abraham Kuyper (1837–1920), the Dutch theologian, philosopher, and statesman, is renowned for his comprehensive vision of Christian engagement in the world, especially in the realms of politics, education, and culture. As one of the founding tenants of Dutch Neo-Calvinism, Kuyper’s theology emphasises the sovereignty of God over every aspect of life and the notion that all spheres of society – such as government, family, and science – operate under God’s authority. Though Kuyper’s years much precede the rise of modern technological advancements like artificial intelligence (AI), his theological principles and philosophical framework offer profound insights into how we might approach the challenges and opportunities presented by contemporary technology.

Kuyper’s Doctrine of Common Grace and Technology

A central aspect of Kuyper’s thought that can be applied to the technological age is his doctrine of common grace. Kuyper articulated this idea as God’s grace sustaining the world even after the Fall, allowing human culture and society to flourish despite sin. Common grace, in Kuyper’s framework, explains why people of faith and of no faith make good and beneficial contributions to society. It provides a theological foundation for the development of technology, science and other socioeconomic advancements.

Technological progress, including AI, is understood as a manifestation of common grace. The ability of humanity to create and innovate is a reflection of God’s sustaining grace in the world. In his major work, On Business and Economics, Kuyper writes:

To work every day that God gives us, to accomplish something that makes up for the length of that day, indeed, to do work so well that when we retire at night the result of the day’s work is finished and ready—that is a divine ordinance. It applies to human beings not just after the fall but also before it. To work and to be busy is our high calling as human beings (page 376).

For Kuyper, the use of human reason, creativity, and ingenuity – faculties given by God to all people – are a demonstration of humanity’s mandate to steward the earth (Genesis 1:28). He viewed work as calling of the highest order. The development of technology can thus be seen as part of the God-given task of dominion over creation. Kuyper would likely view AI as a further step in humanity’s ongoing mandate, where human ingenuity, enabled by God’s common grace, continues to shape and direct the created order.

However, Kuyper also recognized that while common grace permits societal development, sin profoundly distorts human endeavour. This dual reality of grace and sin means that technology, like all human inventions, can be used for both evil and good. AI holds the potential for great benefit – improving healthcare, augmenting human labour, enhancing decision-making processes – but also presents significant ethical challenges, including privacy concerns, job displacement, misinformation, and the potential for dehumanisation.

Having lived in the shadow of the Industrial Revolution and amidst the period of widespread electrification, Kuyper became all too familiar with the repercussions of rapid technological change. He spoke vociferously against the commodification of human capital and had stern words for unscrupulous employers:

The incredible revolution wrought by the improved application of steam power and machine production… has freed capital almost completely from its earlier dependence on manual labour. […] The magical operation of iron machines has unfortunately led the capitalist to regard his employees as nothing but machines of flesh that can be retired or scrapped when they break down or have worn out. […] You [employers] shall honour the workingman as a human being, of one blood with you; to degrade him to a mere tool is to treat your own flesh as a stranger (see Mal 2:10). The worker, too, must be able to live as a person created in the image of God. He must be able to fulfil his calling as husband and father. He too has a soul to care for, and therefore he must be able to serve his God just as well as you (for more on this see Erin Holmberg’s article).

The Imago Dei, Sphere Sovereignty, and the Ethical Use of AI

Kuyper calls for a discerning approach to technology, recognizing both its God-given potential and the inherent risks posed by human sinfulness. At the heart of Kuyper’s anthropology is the belief in the imago Dei – the doctrine that human beings are made in the image of God. This belief undergirds Kuyper’s view of human dignity and responsibility in the world. From this perspective, the ethical use of AI must be grounded in a robust understanding of what it means to be human.

AI, for all its benefits, raises profound questions about human identity and dignity. The automation of tasks traditionally performed by humans, the replication of decision-making processes, and the potential for creating AI that mimics human behaviour challenge our understanding of human uniqueness. Kuyper’s assertion of the imago Dei affirms that human beings are distinct from machines, endowed with moral responsibility, creative capacity, and relationality. Technology, in this view, must serve humanity, not replace or diminish it.

Another key element of Kuyper’s thought is his doctrine of sphere sovereignty. Kuyper proposed that different areas of life – such as education, politics, science, and religion – are distinct spheres, each with its own God-given authority and autonomy. No single sphere, not even the church or government, should dominate the others; each operates according to its own principles and is directly accountable to God.

When applied to AI and technological innovation, sphere sovereignty provides a framework for understanding the limits and responsibilities of technology in society. A Kuyperian approach would caution against excessive forms of influence that overreach into other spheres. For example, AI should not be used to violate personal privacy (an issue in the sphere of human dignity and ethics), nor should it lead to an erosion of political accountability by automating decisions that require human judgment and responsibility.

For Kuyper, the use of AI must be regulated by ethical considerations that prioritize the dignity of human beings. This includes ensuring that AI technologies do not dehumanize individuals by treating them as mere data points or reducing human interactions to automated processes. Instead, AI should be used to enhance human capabilities and alleviate suffering, reflecting the biblical mandate to love one’s neighbour. The goal of technological innovation, according to Kuyper, should be the flourishing of human life in a way that reflects God’s original purpose for creation.

A Kuyperian Vision for AI in the 21st Century

Abraham Kuyper’s theological insights provide a rich framework for thinking through the ethical and social implications of technological advancement. His doctrines of common grace, sphere sovereignty, and the importance of the Imago Dei offer valuable principles for navigating the complex issues raised by AI today.

First, AI can be seen as a product of human ingenuity, a gift of common grace that contributes to our socioeconomic development. Second, Kuyper’s doctrine of sphere sovereignty offers a useful approach to thinking about AI boundaries and ensuring that technology does not usurp the role of human responsibility in areas like justice, politics, and ethics. Finally, AI must remain subservient to human dignity, recognising that humans, made in the image of God, hold unique status and responsibility within creation.

In embracing Kuyper’s vision, Christians are called to engage thoughtfully with AI, recognising both its potential for human flourishing as well as the dangers of misuse. Kuyper’s legacy offers a valuable and theologically grounded approach to the opportunities and challenges of the technological age.

Andrei E. Rogobete is Associate Director at the Centre for Enterprise, Markets & Ethics. For more information about Andrei please click here.

Reports abound on the potential of artificial intelligence to transform workplaces, whether in its capacity to process vast quantities of data – data that would require weeks of careful analysis on the part of human beings – in a matter of hours, or its ability to deal with routine tasks, thus freeing employees to engage more fully with other concerns. Opinion is likely to differ on the benefits of AI at work, but what of its capacity to assist those looking for employment? Generative AI models are apparently being used by growing numbers of job applicants to create CVs and covering letters, in the hope that their applications will stand out from others, which consist of too much text on a white (or plain) background. Anyone who has been involved in recruiting staff will of course be familiar with the phenomenon of receiving a large volume of applications, with a significant number being from candidates who are very similar in terms of qualifications and experience. Thus, the question arises of how to differentiate between them and form an initial judgement about which applicants would appear to be best-suited to the role advertised, and so be called for interview.

The Difficulty of Selection

Such a situation might be described as one in which the recruiting manager has received too many CVs and letters, which consist of too much text on too much plain background – but such a characterisation would be misleading. The difficulty (‘problem’ is surely the wrong term for a situation in which an organisation looking for staff is faced with a wealth of apparently equally well-qualified applicants) is not generally with the ‘presentation’ of applications, but their content. Nevertheless, a belief that ‘appearance’ is what helps an application to stand out seems to lie behind the use of certain AI-enabled features, such as animations or graphics, while in some cases, the letter of application itself is generated automatically from information taken from the advertised post and content from the candidate’s CV.

Outstanding Applications

If the challenge for the recruiter is finding the best candidate(s) for the role, there are very few situations in which this task is likely to be facilitated by an unusual-looking CV. What makes a CV and letter stand out for the right reasons is not that some of the text and plain background have given way to pictures and animations; rather, an outstanding application is one in which the candidate tells the recruiting manager what she needs to know: that is, why this candidate is suitable for the position, how his skills and experience have prepared him for it, and are demonstrative of a genuine aptitude and interest in the role. Eye-catching colours and animations are unlikely to achieve this of themselves. It might be tempting to believe that, based on relevant data pulled from a job description and the candidate’s CV, an AI model will generate a ‘better’ application than the individual can manage himself, but there are almost no situations in which this would produce an outstanding application. It is scarcely surprising if applicants who adopt such an approach often find their applications turned down. If anything, what this method displays is an unwillingness to devote the time to writing an application that demonstrates one’s interest in and suitability for a post – the opposite of what a recruiter would hope to see. Moreover, as reports indicate, where several candidates use the same AI model to produce their application, far from standing out, their applications, somewhat predictably, all appear rather similar.

Applications and the Value of the Individual

This is perhaps indicative of the fundamental reason for which, at present, while artificial intelligence evidently has a role to play in a variety of workplace settings and can, via apps and websites, help those seeking work to find suitable employment, it is difficult to see how it can assist in the application process itself, beyond providing assistance with language or basic formatting. Reports suggest that letters and CVs produced using AI tend to be ‘samey’, which in all probability results from the fact that, ingenious as such technology is, it is likely to produce outcomes to a formula, based on data. The result, while differing in specific details, will therefore be somewhat general. Put differently, the technology is insufficiently capable of focusing on or recognising individuality – both of the role and of the aspiring employee – in ways that matter. (The errors made by AI models in web searches, which produced images of black Nazi soldiers, for example, suggest that the technology certainly can recognise individual difference, but fails to grasp its significance or meaning.) As such, an application based on limited data from a CV and job description, which are then matched, is unlikely to result in a compelling application that captures the attributes and skills of that unique individual, or shows why these make that individual the right person for a particular job. Where employers are serious about seeking suitable individuals (rather than types) for specific roles – and value those employees as individuals – and as long as the purpose of a CV and letter is to demonstrate that the applicant is that individual, the generated (or generic) application is unlikely to serve either recruiter or candidate well.

A Further Consideration

Should the technology advance to a point at which it can produce a convincing application that shows why an individual, with her professional and educational background, qualities and experience, should be considered for a particular role, then AI might well have a role to play. At that stage, it will be important for employers to ask themselves whether there is nonetheless something preferable about a personal application, which would serve to distinguish such candidates; whether, in writing an application herself, a candidate makes a commitment or investment in thought, application and time, that ought not to be delegated to an AI model.

Neil Jordan is Senior Editor at the Centre for Enterprise, Markets and Ethics. For more information about Neil please click here.

This paper is part of a series of essays that seek to explore the current and prospective impact of AI on business. A PDF version can be accessed here.

The previous paper in this series looked at the impact of AI on work through the lens of Peter Drucker’s concept of the ‘Knowledge Worker’. In this paper we turn our attention to existing and emergent evidence on the impact of AI upon worker productivity. We contend that it is misguided to myopically focus on the perpetrated gains in productivity. Equal importance ought to be given to furthering our understanding of the impact of AI upon concepts of meaningful work, self-esteem and job satisfaction. The Judaeo-Christian framework discussed in the first paper in this series offers a moral basis that upholds the importance of human dignity and the intrinsic value of humanity as the sole bearers of the imago Dei (image of God).

The structure here is comprised of three parts. The first will look at both existing evidence and predictions for the impact of AI on productivity, highlighting the often-overlooked time delay between the arrival of new AI capabilities and their materialisation into beneficial productivity tools. The second section turns the attention to matters of meaningfulness, job satisfaction and employee wellbeing in relation to the use and integration of AI tools. The third and final section offers some concluding remarks on how we might begin to think about developing a morally robust symbiosis between AI and work.

‘AI productivity gains may be smaller than you’re expecting’, reads the headline of a recently published report by ING Bank.[1] In May 2023, just 10 months earlier, the Brookings Institute published a research paper titled ‘Machines of mind: The case for an AI-powered productivity boom’[2]. What is the current state of AI when it comes to productivity? Previously we have seen how knowledge worker productivity, though important, presents us with challenges of measurability and accurate prediction. It is important to note here that when talking about AI we are referring primarily to generative AI rather than infrastructure AI which began spreading in the early 2010s and operates largely behind the scenes.

At almost two years from initial public release of ChatGPT we have an emerging story of two tales: there is a dichotomy of evidence between the Macro and Micro levels when it comes to AI-driven productivity gains. Let’s briefly detail some of the existing evidence for each in part.

As of the first half of 2024 there is very little, if any, evidence of AI-driven productivity gains at the Macro level. This perhaps shouldn’t come as much of a surprise since some economists, including Charlotte de Montpellier and Inga Fechner, argue that the biggest impact on productivity growth will be seen in 10-15 years’ time. This assumes that AI does indeed lead to the much-needed complementary innovations that are expected to be dispersed across an array of different fields.[3]

The concept of ‘complementary innovations’ (i.e. innovations that follow and are enabled by the arrival of new technology) is an important one when it comes to gauging the potential impact of AI-driven productivity. General Purpose Technologies like electricity, the internet, personal computers and so on face what is known in productivity theory as a ‘J curve’ (note: ‘GPTs’ – not to be confused with ChatGPT which stands for Generative Pretrained Transformer).[4] This holds that the arrival of new GPTs counterintuitively leads to an initial decrease in short-term productivity measurements followed by a gradual increase in the medium-to-long term productivity – closely resembling a ‘J curve’. The J curve is largely due to difficulties in accurately measuring the initial GPT adoption investment in intangible capital, as economists like Erik Brynjolfsson et al.[5] point out:

As firms adopt a new GPT, total factor productivity growth will initially be underestimated because capital and labour are used to accumulate unmeasured intangible capital stocks. Later, measured productivity growth overestimates true productivity growth because the capital service flows from those hidden intangible stocks generates measurable output. The error in measured total factor productivity growth therefore follows a J-curve shape, initially dipping while the investment rate in unmeasured capital is larger than the investment rate in other types of capital, then rising as growing intangible stocks begin to contribute to measured production.[6]

So it would be reasonable to assume a degree of delay between the period of initial investment, development and adoption of AI tools, and their derived productivity increases at the Macro level. Some long-term predictions remain optimistic: Goldman Sachs estimates a 7% (or almost $7 trillion) increase in global GDP and a lift in productivity growth by 1.5 percentage points over a 10-year period – though it should be noted that this estimate is dependent upon AI’s future capabilities and adoption rates.[7] Other predictions are more conservative: Daron Acemoglu, Professor of Economics at MIT, estimates that AI-driven GDP growth is unlikely to exceed circa 0.93% − 1.16% over the next 10 years, with a total factor productivity (TFP) of no more than 0.66% over the same period.[8]

Thankfully, at the Micro level the picture is less murky. About half a dozen studies provide us with reliable data, three of which will be discussed here. The first is authored by E. Brynjolfsson, D. Li and L. Raymond and looked at the effects of using a generative AI conversational assistant (or AI chatbot) by 5,179 customer support agents.[9] This likely represents the largest generative AI-workplace study of 2023 and its findings point to some positive outcomes for AI integration within this particular business scenario.

The productivity of each customer support agent was measured in resolutions per hour (RPH). Those that worked with the assistance of the AI chatbot completed on average 14% more RPH than those who didn’t.[10] The research also found that ‘AI assistance improves customer sentiment, increases employee retention, and may lead to worker learning’.[11]

What is even more interesting is the dispersion amongst high-skilled and low-skilled workers. Figure 1 illustrates the change produced in RPH (y-axis) following AI deployment to the lowest skilled workers (x-axis, Q1), through to the highest skilled workers (x-axis, Q5). The results point to a significant productivity gain of 35% for the lowest skilled workers (Q1), but negligible change in productivity for the highest skilled workers (Q5).[12]

The study found ‘… suggestive evidence that the AI model disseminates the best practices of more able workers and helps newer workers move down the experience curve’.[13] In other words, the AI chatbot proved to be an effective tool at learning from the best resolutions for certain problems and distributing this knowledge at greater pace and with higher accuracy to the most novice and low-skilled employees. It is important to note that the AI chatbot in this particular study was designed to augment and assist each particular issue and resolution. The final decision of whether to adopt or reject the AI’s suggestions remained entirely at the discretion of the customer support agent.[14]

A second notable study by S. Peng et al. looked at GitHub’s ‘Copilot’, an AI assistant utilised in computer programming.[15] A group 95 programmers recruited via Upwork, a freelance jobs platform, were tasked with implementing an HTTP server in JavaScript as quickly as possible (though the technical details are not essential for the lay reader). Of the 95 programmers, 45 were in the treated group and 50 in the control group. Performance was measured by (A) task success and (B) task completion time. The results revealed no difference of statistical significance in (A) task success – in other words, both groups completed the challenge with a high rate of success. However, the results did show a 55.8% decrease in (B) completion time for the treated group compared to the control group. This translates to 71.17 minutes versus 160.89 minutes – a net reduction in completion time of 89.72 minutes for the treated group of programmers that utilised GitHub Copilot.[16] It is important to note however, that the study did not evaluate the quality of the code produced by the two groups, and discrepancies here may be significant for the real-world impact of relying on AI tools in programming.[17] So programmers that utilised GitHub’s Copilot finished the challenge an average of 1h 30min quicker than those who did not.

The third study worth mentioning is entitled ‘Experimental Evidence on the Productivity Effects of Generative Artificial Intelligence’, authored by S. Noy and W. Zhang, both from MIT.[18] As the title suggests, the research took an empirical look at the effects of using ChatGPT for a variety of mid-level business-related writing tasks.[19] The study recruited 444 professionals with a higher degree of experience from fields such as data science, human resources, consultancy and marketing. They were all tasked with completing 20–30-minute assignments such as writing a more important email, a short report, press releases, an analysis of various bits of data and so on – all encounters designed to resemble a real-world work environment.[20]

Between task 1 and task 2, 50% of the participants (i.e. the treatment group), were given the possibility of using ChatGPT for their second task (neither group used AI for the first task). The results in productivity were measured in earnings per minute, with each piece of final documentation being independently evaluated for content quality, writing and originality, and assigned a score. The results reveal a substantial increase in productivity by reducing the average task completion time from 27 minutes to 17 minutes. What is perhaps more interesting is that the blind evaluations in quality produced reveal an improvement of 4.54 with ChatGPT versus 3.79 without (on a scale of 1-7).[21]

The evidence presented thus far broadly points to the adoption of generative AI tools having a positive impact on productivity. However, myopically focusing on productivity gains at the expense of other factors that are relevant to work such as meaning, self-esteem and job satisfaction, risks giving us a distorted and incomplete understanding of the multifaceted implications of adopting and integrating generative AI within the workplace. Indeed, a closer look at some of the relevant studies reveal a more complex picture. Let’s start with the concept of meaning and self-esteem.

In philosophy the relationship between work and meaning is well-established, with notable studies by Diddams and Whittington,[22] J.B. Ciulla,[23] C. Michaelson[24] and others. Within the social sciences we also find a convoluted landscape that encompasses meaningful work, drawing upon contributions from organizational studies, psychology, economics, political theory, and sociology.[25] [26] What exactly does it mean for something to take on the adjective ‘meaningful’? The etymology of the word ‘meaning’ expresses the importance or value of something.[27] To become ‘meaningful’ is to give significance, intentionality and a purpose that pervades the action or the subject in question.

Work is therefore not just a means of economic survival but also a fundamental source of self-identity, worth, and purpose. Work carries repercussions that move beyond the mere intellectual or physical act itself. C. Cordasco from the University of Manchester highlights two broad categories from which work derives meaning and self-esteem: intrinsic and extrinsic. Intrinsic factors involve pride in one’s unique personal or collective skills, a genuine interest and enjoyment in the work itself (be that physical or cerebral) and contributions to an organisation or indeed a wider field. Extrinsic factors include the ability to provide for oneself and one’s family, the recreational freedom that work provides, the affiliation with certain groups and social networks, and so on.[28]

The first paper within this series we considered a Judaeo-Christian approach to AI and work. We highlighted how this implicitly raises wider questions of purpose, meaning and a sense of calling that pervades the mere temporal dimension of work. The Judaeo-Christian perspective therefore seeks to re-evaluate of the gift and place of human agency and responsibility within creation. The foundational texts can be found in Genesis 1:28 and 2:15 where humanity is called to ‘Be fruitful and increase in number; fill the earth and subdue it. Rule […] over every living creature that moves on the ground. […] The Lord God took the man and put him in the Garden of Eden to work it and take care of it.’[29] The command here is here is one of teleological reflection through human capabilities of that which is divine: humanity is given freedom and authority to order, create, steward, and against the backdrop of original sin, also to destroy.

Judaeo-Christian teaching therefore places the concept of work as a key part of what it means to be made in the Imago Dei (the image of God), and to actively partake in the eschatological realisation of creation. Work is thus an integral element of Christ’s redemptive transformation of the individual and indeed the world. Meaning therefore, finds its ultimate source in the creator God, and this of course encompasses meaning within the realm of work. It is a distinctly human pursuit – no other species on earth searches for meaningful work. Indeed, no other species even reaches a point of asking the question: ‘Why am I doing what I am doing?’. As David Atkinson rightly points out in his commentary on Genesis: ‘To be in his image is to be aware of ourselves as his creatures’.[30]

This ability for profound self-reflection is a core characteristic of what it means to be image bearers of the divine. It informs and shapes the meaning of work: if humanity has been gifted with intellectual abilities such as creativity, problem-solving skills, discernment, a capacity to learn new skills and to avoid past mistakes, and has been entrusted with these abilities to care for and steward over creation, then anything that risks compromising these qualities warrants careful attention and scrutiny. The Judaeo-Christian perspective on meaningful work is in some sense dualistic: on one hand God is the ultimate source of purpose and meaning, and on the other, human capabilities play a role in fulfilling and partaking in the larger narrative of God’s redemption of creation.

If we turn back to AI, what is the likely impact going to be on meaningful work and job satisfaction? The evidence, while still in its infancy, is patchy. Emergent studies point to both positive and negative outcomes. S. Noy and W. Zhang found that augmentation with ChatGPT in the variety of common office tasks, ‘…increases job satisfaction and self-efficacy and heightens both concern and excitement about automation technologies’.[31] The study points out that the recorded increases in job satisfaction are likely due to a heightened sense of achievement when completing a more difficult or tedious task with the assistance of ChatGPT, and in a shorter amount of time than would have otherwise been possible.[32]

However, another study by P.M. Tang et al. cautions against an overdependence on AI systems as a leading factor in social disconnection and worker loneliness:

This coupling of employees and machines fundamentally alters the work-related interactions to which employees are accustomed, as employees find themselves increasingly interacting with, and relying on, AI systems instead of human coworkers. This increased coupling of employees and AI portends a shift towards more of an “asocial system” wherein people may feel socially disconnected at work.[33]

Similarly, C. Cordasco points out that while AI development poses a significant threat to traditional sources of self-esteem derived from work, halting AI is neither feasible nor the best solution. Instead, society should explore new ways of cultivating self-esteem that align with the evolving technological landscape.[34]

A report by Boston Consulting Group’s (BCG) Henderson Institute investigated how people can ‘create and destroy’ value with Generative AI and found that, ‘…it isn’t obvious when the new technology is (or is not) a good fit, and the persuasive abilities of the tool make it hard to spot a mismatch. This can have serious consequences: When it is used in the wrong way, for the wrong tasks, generative AI can cause significant value destruction’.[35] The study had access to over 750 BCG consultants as subjects and found that in areas such as creative product innovation, AI tools boosted productivity by 40%, but in areas like business problem solving, generative AI actually led to a 23% reduction in productivity. The report also highlighted an important trade-off when it comes to collective creativity. Whilst individual performance may be boosted by 40%, collective diversity of ideas may fall by 41%. This is largely because AI chatbots tend to produce the same or similar responses to the same specific prompts – resulting in positive outcomes at the individual level but repetitive and less diverse outcomes at the collective level.[36] The potential impact of AI tools on human creativity also seems to be an issue of concern: out of a group of 60 BCG consultants, 70% expect a negative impact on creativity, 26% do not anticipate a negative creative impact, and 4% are unsure.[37]

It is important to note that when attempting to draw conclusions about the impact of AI upon the world of work, we are (whether we like it or not), operating along several core variables, or axes. The first would be the level of automation (high) versus augmentation (low). The second represents the level of skill of the employee or group of employees in question. Here it is becoming increasingly apparent that there seems to be a positive reduction in productivity inequality, with at least in these nascent stage, low-skilled workers standing to benefit the most from AI tools. There is also a challenge of AI discernment, what some authors have called a ‘jagged technological frontier’, whereby the most successful employees and managers will learn to distinguish which tasks are best suited for AI assistance and which aren’t.[38] The third is perhaps less a variable than a recognition that the business world represents a plethora of highly distinct work contexts and scenarios where AI implementation may or may not play an important role.

All of these factors are essential when attempting to understand the impact that generative AI has upon work. Broadbrush conclusions about the impact of AI are at best generic, and at worst, inaccurate. Therefore, at least in these early stages, we have to operate on a case-by-case basis and seek to identify and understand areas where AI is a net contributor, and not a hindrance, to both productivity and matters surrounding meaningful work.

Central to the Judaeo-Christian framework is the importance of humanity as the sole image bearer of the divine, tasked with responsibilities of stewardship over nature. In fulfilling the stewardship command, humanity also has the duty of recognising and protecting distinct human attributes such as meaning, purpose, self-esteem and creativity. Emergent technologies therefore ought to be developed and harnessed in harmony with the qualities conferred by humanity’s uniqueness, not against them.

Andrei E. Rogobete is Associate Director at the Centre for Enterprise, Markets & Ethics. For more information about Andrei please click here.

[1] Charlotte de Montpellier, Inga Fechner, ‘AI productivity gains may be smaller than you’re expecting’, ING Bank, April 2024, https://think.ing.com/articles/macro-level-productivity-gains-ai-coming-artificial-intelligence-the-effect-smaller/.

[2] Martin Neil Baily, Erik Brynjolfsson, Anton Korinek, ‘Machines of the Mind: The Case for an AI-powered Productivity Boom’, Brookings Institute, May 2023, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/machines-of-mind-the-case-for-an-ai-powered-productivity-boom.

[3] Charlotte de Montpellier, Inga Fechner, ‘AI productivity gains may be smaller than you’re expecting’, ING Bank, April 2024, https://think.ing.com/articles/macro-level-productivity-gains-ai-coming-artificial-intelligence-the-effect-smaller/.

[4] Erik Brynjolfsson, Daniel Rock, Chad Syverson, ‘The Productivity J-Curve: How Intangibles Complement General Purpose Technologies’, American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, Vol. 13(1): 333-72, (January 2021), DOI: 10.1257/mac.20180386.

[5] Ibid. p.1

[6] Ibid. p.3

[7] Goldman Sachs, ‘Generative AI could raise global GDP by 7% ‘, April 2023, https://www.goldmansachs.com/insights/articles/generative-ai-could-raise-global-gdp-by-7-percent.html

[8] Daron Acemoglu, ‘The Simple Macroeconomics of AI’, paper prepared for Economic Policy, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, (April 2024), p.4.

[9] Erik Brynjolfsson, Danielle Li, Lindsey R. Raymond, ‘Generative AI at Work’, National Bureau of Economic Research – Working Paper 31161, https://www.nber.org/papers/w31161.

[10] Ibid. p.10

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid. p.15

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid. p.9

[15] Sida Peng, Eirini Kalliamvakou, Peter Cihon, Mert Demirer, ‘The Impact of AI on Developer Productivity: Evidence from GitHub Copilot’, arXiv Accessibility Forum, (February 2023), arXiv:2302.06590 [cs.SE].

[16] Ibid. p.5

[17] Ibid. p.8

[18] Shakked Noy, Whitney Zhang, ‘Experimental Evidence on the Productivity Effects of Generative Artificial Intelligence’, Science, Vol. 381(6654): 187-192, (July 2023), DOI: 10.1126/science.adh2586.

[19] Ibid. p.1

[20] Ibid. p.2

[21] Ibid. p.4

[22] Margaret Diddams, J.Lee Whittington, Daniel T. Rodgers, Joanne Ciulla, ‘Book review essay: Revisiting the meaning of meaningful work’, Academy of Management Review, Vol. 28(3):508-512, (June 2003), DOI: 10.2307/30040737.

[23] J. B. Ciulla, The working life: The Promise and Betrayal of Modern Work, (London: Times Books, 2000), pp.266.

[24] Christopher Michaelson, ‘Meaningful motivation for work motivation theory’, Academy of Management Review, Vol. 30(2): 235-238, (April 2005), https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2005.16387881.

[25] Ruth Yeoman (ed.), Catherine Bailey (ed.), Adrian Madden (ed.), Marc Thompson (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Meaningful Work, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019), pp.544.

[26] Catherine Bailey, Marjolein Lips-Wiersma, Adrian Madden, Ruth Yeoman, Marc Thompson, Neal Chalofsky, ‘The Five Paradoxes of Meaningful Work: Introduction to the special Issue ‘Meaningful Work: Prospects for the 21st Century’’, Journal of Management Studies, Vol. 56(3): 481-499, (May 2019), https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12422.

[27] Cambridge Dictionary, ‘Meaning, (July 2024), https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/meaning.

[28] Carlo Ludovico Cordasco, ‘Should We Halt AI to Protect Meaningful Work?’, ResearchGate, (December 2023), DOI: 10.13140/RG.2.2.22893.77288, p.7-18.

[29] The Holy Bible, (NIV Translation).

[30] David Atkinson, The Bible Speaks Today Series: The Message of Genesis 1—11: The Dawn of Creation, (Westmont, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1990), p. 37.

[31] Shakked Noy, Whitney Zhang, ‘Experimental Evidence on the Productivity Effects of Generative Artificial Intelligence’, Science, Vol. 381(6654): 187-192, (July 2023), DOI: 10.1126/science.adh2586. p.1.

[32] Ibid. p.9

[33] Pok Man Tang, Joel Koopman, Ke Michael Mai, David De Cremer, Jack H. Zhang, Philipp Reynders, Chin Tung Stewart, and I-Heng Chen, ‘No Person Is an Island: Unpacking the Work and After-Work Consequences of Interacting with Artificial Intelligence’, Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 108(11): 1766–1789, (2023), https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0001103.

[34] Carlo Ludovico Cordasco, ‘Should We Halt AI to Protect Meaningful Work?’, ResearchGate, (December 2023), DOI: 10.13140/RG.2.2.22893.77288, p. 35-36.

[35] François Candelon, Lisa Krayer, Saran Rajendran, and David Zuluaga Martínez, ‘How People Can Create—and Destroy—Value with Generative AI’, Boston Consulting Group Henderson Institute, (September 2023), pp. 21.

[36] Ibid. p.15

[37] Ibid. p.16

[38] Fabrizio Dell’Acqua, Edward McFowland III, Ethan Mollick, Hila Lifshitz-Assaf, Katherine C. Kellogg, Saran Rajendran, Lisa Krayer, François Candelon and Karim R. Lakhani, ‘Navigating the Jagged Technological Frontier: Field Experimental Evidence of the Effects of AI on Knowledge Worker Productivity and Quality’, Harvard Business School, Working Paper 24-013, (June 2024), p.2.

As part of the new government’s effort to raise the number of houses built and spur economic growth, Labour ministers plan to allow homebuilders to receive planning permission for projects currently impacted by nutrient neutrality rules that require new construction in areas with high levels of nutrients in waterways to not contribute additional nutrients. The permission would be granted with so-called Grampian conditions (the name derives from a Scottish legal case) that would allow the homebuilding to begin subject to future off-site mitigation, rather than the status quo which requires the mitigation to be worked out before the homebuilding begins. This is one quick way that the government seeks to address the fact that because of nutrient neutrality homes impacting much of the country, homes can only be built after the details of mitigation are worked out. This is a huge administrative burden and is holding up something like 160,000 homes from being built. Few think that this will solve the issue, but it is a positive development and one of a number of efforts dealing with environmental concerns. Past efforts have failed to fix the issue and descended into rancorous debates, despite the specific issue of pollution from new homes being minimal.

The crux of the issue in question is that in recent years the environmental concerns surrounding nutrients like phosphates and nitrates in rivers have meant that because of new court rulings, new homes in a large proportion of the UK must mitigate all run-off that they would create.[1] Nutrient runoff into rivers causes algal blooms which consume oxygen and set off a chain of species die offs. European and British court rulings have widened the impact of the rules, including most recently applying the rules to projects which had already received planning permission.

This plan was suggested by Angela Rayner and Steve Reed last September when the last government attempted to overhaul the rules surrounding nutrient neutrality more comprehensively. That effort failed when the House of Lords defeated the Government’s plan to remove the legal requirements on homebuilders while increasing taxpayer funding of a more comprehensive scheme. At the time, the Labour Party was expected to support the reform but altered course just days before the vote. For those who haven’t been following the issue closely, much of the commentary on it in the main newspapers offers little insight and instead treats it as an elementary decision on a good environmental outcome or a poor one. Rather than going through the tangled legal history—I’ll leave that to those who charge by the hour (e.g. Zack Simons or Simon Ricketts)—I want to focus on how this issue and the failure to fix it has been emblematic of a broader problem with environmental issues.

What is the Problem with the Status Quo?

The problem with the current situation, one recognized by many experts, is that it places an extraordinary burden on a socially useful function: residential development. Taking as a given that the levels of nutrient pollution outlined in the rules are sensible, it is reasonable to want to limit any pollution that might occur beyond that point. When rivers reach a point where added pollution is unacceptable—as Natural England claims to be the case in 74 local authorities across the UK including most of Norfolk, much of Wiltshire and Somerset, and the area around the Solent—it makes sense to stop it from getting worse. As a result of this worthy cause, the rules are estimated to be holding up over 160,000 homes (a number that will continue to grow).

In principle, it could be reasonable to stop the market from building more much-needed houses because once the harm of the marginal nutrients is considered there is no net value being created. However, the marginal pollution created by people living in new homes is tiny. In fact, the pollution directly created by all structures (i.e. including existing structures) is supposedly just 5% of the total.[2] Basic economics suggests that there are many ways to regulate such that valuable uses like homebuilding proceed while paying for the reduction in pollutants in whatever way can be done at the lowest cost.

In fact, this is what is supposed to be happening now. The rules are supposed to set a budget for the total amount of nutrients in an impacted area and allow new homes if the developers offset the added pollutants by the same amount. This should encourage bargaining between homebuilders and other polluters. Homebuilders should be able to pay agricultural users who are the biggest polluters and who could reduce pollution at much lower abatement cost than homebuilders. This abatement could be achieved by farming less intensively by using fewer polluting fertilizers or by letting land go fallow. Alternatively, homebuilders could pay for methods to capture agricultural producers’ pollutants, or be able to pay water companies whose disposal of wastewater is one of the key mechanisms by which disparate users’ waste ends up in waterways. The benefit of such a type of regulation is that it creates market incentives to deal with the environmental problem at the lowest cost.

These are examples of the type of offsite mitigation schemes encouraged by the proposed reforms that (at a minimum) will net out the impact of the new development by reducing the relevant pollutants that new housing contributes. This would allow much needed new homes at a much lower cost than catching all added nutrients via onsite mitigation, while also keeping rivers limited to the same level of nutrient runoff. The rules allow nutrient offsetting schemes (and some have been worked out) but they don’t work well in practice due to procedural barriers. There is no environmental or economic reason for this to not be encouraged.

However, as Zack Simons writes:

Nutrient neutrality involves quantifying a ‘nutrient budget’ for both phosphorous and nitrogen, and then using either on or off-site mitigation measures to show that your scheme will not cause any net harm to the protected sites – see some guidance from Natural England here. Measures might include e.g. creating new wetlands, retrofitting sustainable urban drainage systems and making arable farmland fallow to reduce nitrates. But in many authorities, there simply is no standard nutrient neutrality strategy. Or no strategy at all. Very often, nutrient neutrality simply cannot yet be achieved – either viably, or at all.

As bad as the status quo which emerged from legal machinations is, perhaps more worrying is the fact that this issue, like many others, has become mired in unthinking partisan debate. Perhaps the worst offenders are the environmental groups whose interest in the issue suggests that they must realize the need for a better, more comprehensive regulatory system, but who instead depict the problem as a result of homebuilders’ actions.

Like many other countries in Europe, the UK is and has been facing a dramatic set of economic headwinds. Real reforms are needed to enable investment in green energy generation and transmission, but these too face opposition from those who would be expected to support them. Let us hope that this government can fix what the last couldn’t.

[1] The rules allow pragmatic schemes to mitigate nutrient pollution offsite, but the process for doing so is unnecessarily complicated.

[2] Baroness Willis of Summertown suggests that this number may be closer to 30%. But this makes little difference for this argument given this still suggests that the marginal addition is quite small, since the number of existing homes is far larger than the number of new homes held up.

John Kroencke is a Senior Research Fellow at the Centre for Enterprise, Markets and Ethics. For more information about John please click here.

John Kroencke is a Senior Research Fellow at the Centre for Enterprise, Markets and Ethics. For more information about John please click here.