Andrei Rogobete: The Cost of Living Crisis Will Hit Savings Hard

The economic headwinds facing Britain seem to be evermore penetrating – recently we have seen:

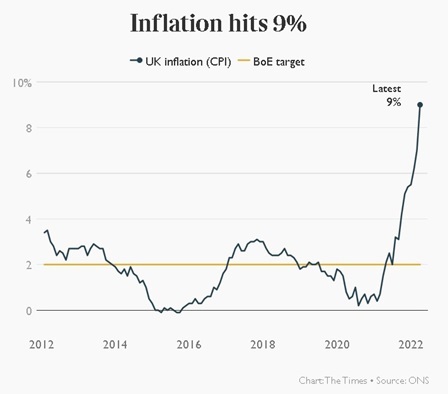

Inflation hit a 40-year high of 9%

Largely driven by the increase in utility prices and the higher energy price cap that came into effect (see chart below). ONS chief economist, Grant Fitzner said that, “Around three quarters of the increase in the annual rate [of inflation] this month came from utility bills.” CEME Chairman Brian Griffiths has written extensively on the issue and has warned on repeated occasions about the threat and ills of inflation. In his first article entitled The Spectre of Inflation written back in August 2020 he wrote that,

“We must take the prospect of inflation seriously. […] To allow inflation to rise would be a failure to learn the lessons of history. […] Controlling inflation is painful. It requires the central bank to raise interest rates. […] Each time interest rates have been raised, inflation has been brought down, but only at the cost of increased unemployment”.

The markets have seen their biggest drop since the pandemic began in March 2020

Two years later and we are very much in this ‘painful’ phase of stemming inflationary prices through (an increasingly) contractionary monetary policy. Yet, we are only at the start of beginning to feel the economic and social consequences of rising interest rates.

The S&P 500 briefly fell into bear market territory dropping more than 20% since its previous record high. £40bn has been wiped off the FTSE 100 intensifying fears that the UK is heading for a recession. The online news outlet and portal ThisIsMoney asks, “Is a recession inevitable as inflation hammers the UK and interest rates are hiked?”

Energy prices of course have reached record highs rising by 54% in April 2022 alone

The average household currently pays just under £2,000 in annual energy bills but modelling conducted by E.ON suggests this could rise to £3,000 by October 2022. Ofgem Chief Executive Jonathan Brearley confirmed that energy prices will likely hit £2,800 this year and that this is a “once in a generation event not seen since the oil crisis in the 1970s”. Lower income households may be faced with spending as much as 40% of their disposable income on energy, leaving millions of people in fuel poverty (as many as 12 million according to Mr Brearley).

What does this mean for savings?

At first glance, rising prices will mean that households and in particular those on low incomes may find themselves having to ‘break the piggy bank’ to make ends meet. That is of course, if they are in the more fortunate position of having a piggy bank in the first place. For many, it will mean sacrificing long-term funds for short-term survival – placing households in the potentially tr situation of having no financial resources at all. Worse yet, some will be forced to take on additional debt that may prove unsustainable, meaning that families and individuals could rather quickly find themselves in a dangerous financial pit.

The most recent Quarterly Outlook (May 22’) of the National Institute of Economic and Social Research (NIESR) found that, “1.5 million households (5% of the population) have food and energy bills greater than their disposable income. For these households, who likely do not have sufficient savings or access to credit cards to help them cope with these prices, we can expect them to either resort to payday loans, or simply not pay their bills by going into arrears and incurring more long-term debt.”

So those with savings are facing a difficult challenge. Inflationary pressures will continue to reduce the value of existing savings over time and rising costs are forcing more and more households to dip into savings for their daily sustenance. The savings ratio has plummeted from the pandemic high of 23.9% in Q2 of 2020 to 6.8% in Q4 of 2021 (ONS) – we can only expect this to drop further.

There are no easy solutions to this complex post-pandemic economic environment. In the short-to-medium term inflation has to be brought down, meaning that the BOE will have to continue to rise interest rates. Yet this may also be an opportune moment for the Treasury to reverse some of the previous National Insurance hikes and offer a tax cut to the working population and business in general (perhaps a reduction in VAT seems appropriate?). This would not only send the right message to the markets, it would also boost confidence and offer many small to medium-sized enterprises a much needed lifeline to counter rapidly spiralling costs.

Supply side fiscal responses proved successful in the Ragan/Thatcher era of the 70s and 80s. The Federal Reserve under Paul Volker brought down US inflation from 13.5% in 1980 to 4.1% in 1988 (interest rates remained relatively high throughout the 80s), whilst ‘Reaganomics’ promoted economic growth. GDP under the Reagan Administration averaged 3.5%; compared to George H.W. Bush at 2.25%; Bill Clinton 3.88%, George W. Bush 2.2% and Barack Obama 1.62%. Similarly, inflation in the UK under Thatcher dropped from almost 18% in 1980 to around 3% in 1987.

Quick and sustained action is needed to bring down inflation. Higher interest rates need to be balanced with supply-side policies. It is unfortunate that the tax burden has reached its highest level in 70 years under a Conservative government, while many are struggling to afford the daily basics. The problem is that the Conservatives risk losing their once-held credibility on economic matters as the former Brexit Secretary David Davies pointed out, “It’s a real risk now that the party is going to lose its reputation for economic competence.” The tide must be turned before it is too late.

Andrei E. Rogobete is Associate Director at the Centre for Enterprise, Markets & Ethics. For more information about Andrei please click here.