Steve Morris continues his series on lost management gurus

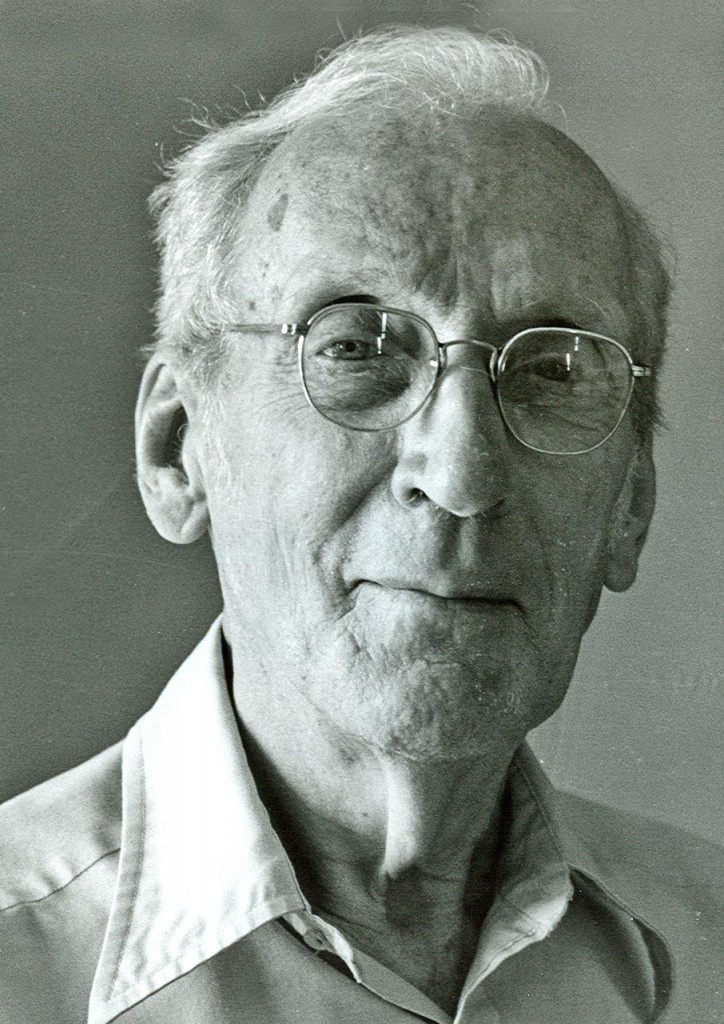

It is 1969 and campuses in the US are alive with revolt and turmoil. The anti-Vietnam protests are getting serious and America looks like it might fracture. It was time for a little-known educator, born in 1904 in Terre Haute, Indiana, to propose a way of succeeding without trampling on each other. His name was Robert K Greenleaf.

Greenleaf was no academic star. He graduated with a modest maths major in 1926 from Carleton College in Minnesota. Indeed, he was always sceptical that simple academic prowess was enough to really change anything. Greenleaf joined US telecoms giant AT&T and over the years rose steadily and had a major impact on that business. He acted as a troubleshooter and educator. It was during this period that he had a breakthrough: that the organisations that really succeeded tended to have good management but of a specific kind. In these organisations, leaders were coaches not tyrants. As he put it: “The organisation exists for the person as much as the person exists for the organization.”

This was certainly not a popular view at the time and still looks like the world seen upside-down. Greenleaf’s road to Damascus moment was reading an obscure novella by German writer Hermann Hesse – The Journey East. It is a truly odd little book, I know because I’ve read it, and pictures a strange mystical journey by a bunch of seekers. They are backed up by a person called Leo who serves the team selflessly. He is easy to miss, but when he suddenly leaves, the mission collapses. It seems that the humble servant was, in fact, the leader.

Greenleaf took this insight and produced his seminal essay The Servant as Leader in 1970. In it, he proposed that the best leaders were servants first, and the key tools for a servant-leader included listening, persuasion, access to intuition and foresight and use of language. As he put it, “The servant-leader is servant first… It begins with the natural feeling that one wants to serve, to serve first.” And in this, we begin to see the slightly fuzzy edges that make the idea hard to pin down. The question arises, are you born with this instinct and what happens if you aren’t?

Over time, Greenleaf expanded on his idea and a fuller picture of the servant leader emerged. A Servant Leader shares power, puts the needs of the employees first and helps people develop and perform as highly as possible.

It is deeply challenging, because it takes issue with the corporate mentality that says always put the customer first. What if the needs and development of those who work for you have at least an equal call on your good offices?

Greenleaf came up with a useful test to measure how well an organisation is doing. Have you got things round the right way?

“Do those served grow as persons? Do they, while being served, become healthier, wiser, freer, more autonomous, more likely themselves to become servants?”

Greenleaf retired from AT&T and made servant leadership his life’s work. It still has devotees and it is hard not to feel warm to the idea. Greenleaf became a Quaker in later life and his ideas certainly owe a great deal to Judeo-Christian ideas. Indeed, Greenleaf frequently quotes the Bible and the actions of Jesus.

So why is it that I feel a little unconvinced? It is in part, my uneasiness with anyone taking on the role of prophet and guru. I find myself asking, ‘Who says?’ Why have you alone suddenly worked all this out? I simply mistrust people who seem to have cracked it.

Also, does servant leadership give us the full picture. Are there times when directional leadership is called for? Are there times and situations where we simply have to get on with things even if we don’t grow or thrive? Are there places where it is most likely to work. Perhaps servant leadership may thrive in places where there is no promotion to be scrambled for, or where people come into leadership later in life and don’t aim to climb the greasy pole, as Disraeli put it.

I ask the people around me what they think and if they have ever had one of these servant leaders. Rather sadly, perhaps, none of them can think of anyone.

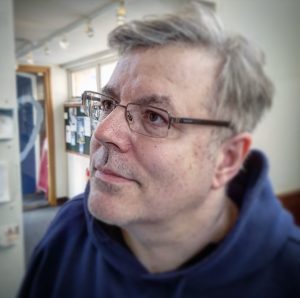

Steve Morris is the Vicar of St Cuthbert’s, North Wembley, an entrepreneur, and the author of several publications for CEME and beyond including Enterprise and Entrepreneurship, and Lessons from Family Business, both available from the CEME office. He is married, with two children and has three cats. His latest writing, Our Precious Lives, dealing with the power of story-telling is available here.

Steve Morris is the Vicar of St Cuthbert’s, North Wembley, an entrepreneur, and the author of several publications for CEME and beyond including Enterprise and Entrepreneurship, and Lessons from Family Business, both available from the CEME office. He is married, with two children and has three cats. His latest writing, Our Precious Lives, dealing with the power of story-telling is available here.