Edward Carter: “The Biblical Entrepreneur’s Experience” by S Leigh Davis

Much of The Biblical Entrepreneur’s Experience comprises a rather simplistic and selective use of scripture to support a particular world-view, namely a North American free market system. As such, it could almost be categorised as espousing a prosperity gospel, in which correctly following biblical methods will necessarily bring success in business (see Chapter 2 for Davis’s “system”). The examples given in the book, of entrepreneurs such as Sarah Breedlove (Madam C.J. Walker), Strive Masiyiwa and Scott Harrison, tell this story in an often engaging way, but at times verge on a parody, which attempts to represent the complex riches of the Christian faith in an unreflective manner. One example is the song “The Hairdresser’s Ode to Madam C.J. Walker”, to the tune of “Onward, Christian Soldiers”, which the author cites approvingly (pages 72-73). The ‘mission’ of beautifying hair is conflated completely with the great Christian Commission in a manner that I found both disturbing and shallow.

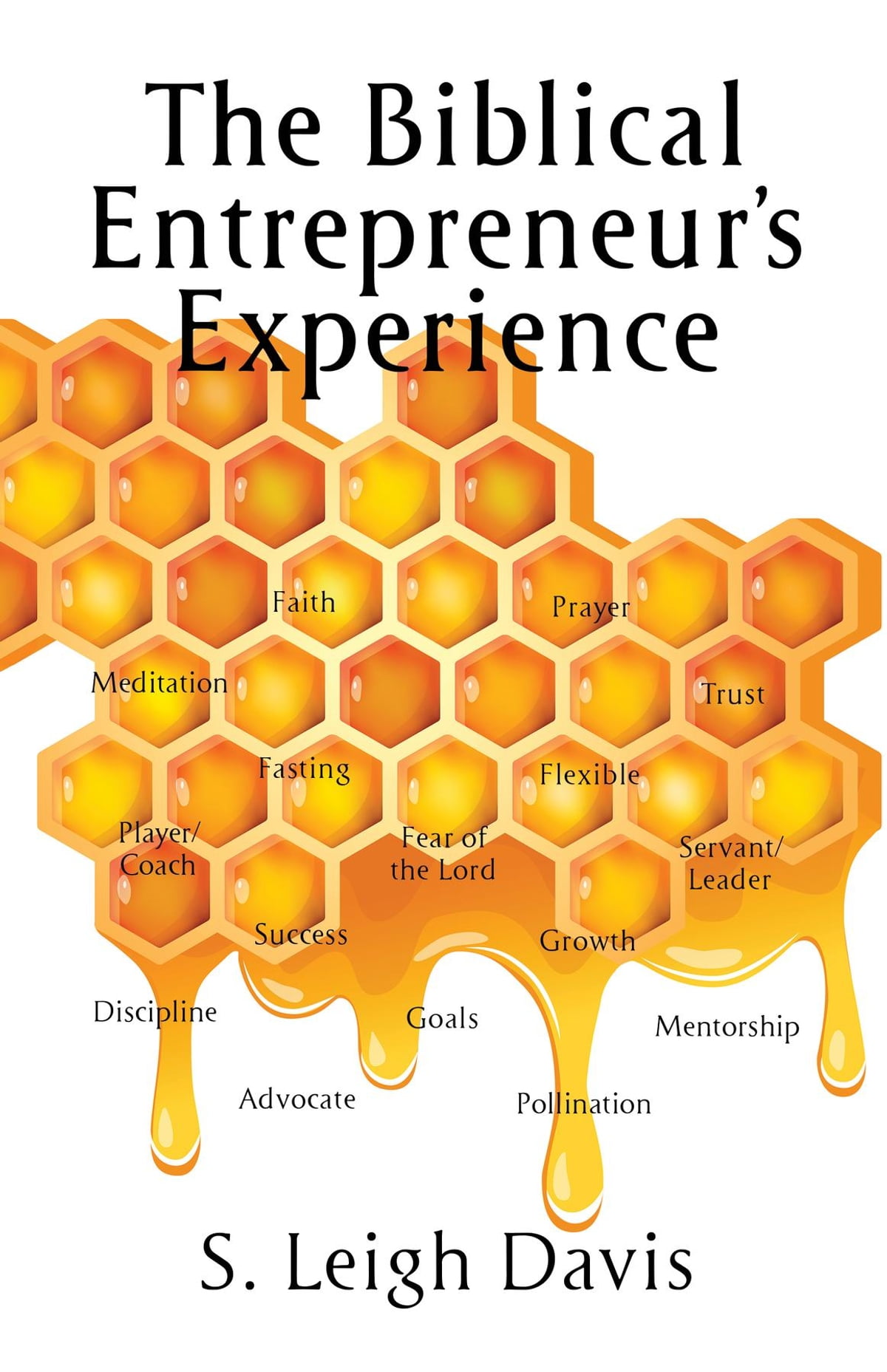

Davis’s central metaphor, akin to a sermon illustration, is that of ‘bees and fleas’, and the author uses the bee/flea imagery to invite the reader into his world-view. BEEs (Biblical Experiential Entrepreneur) are good, and FLEAs (in-Flexible Learnt Entrepreneurial Antagonist) are bad. At the heart of Davis’s analysis is the proposition that “A BEE creates; a FLEA takes” (page 22). The book is peppered with “fun facts”, such as, “The honeybee has a heart!” (page 143), and side-bar notes, for example, “Strive – to devote serious effort or energy; to struggle in opposition” (page 115). Taken together, the above makes the overarching style of the book quite propositional and un-nuanced.

However, at times the book is also informative and every now and again I was pleased to find an interesting comment or statement that, I felt, contributed in a thoughtful way to a theological consideration of the subjects of enterprise and of entrepreneurial behaviour. For example, on the theme of entrepreneurial endeavour, Davis suggests: “It is to prepare the entrepreneur for the next life: a venture more fulfilling than its worldly counterparts” (page 5). This statement sketches out an idea which could be developed into some deep vocational thinking on the kingdom of heaven, and the place for enterprise within God’s enduring purposes. In another intriguing statement Davis comments: ‘…through grace we are given a great opportunity to provide others with a needed product or service to glorify Him – not ourselves” (page 11). Here, the themes of God’s grace, human need (not desire), and divine glory are all connected together under the umbrella of enterprise.

In Chapter 6 biblical examples are used to support the practice of “active listening”, as a way of harnessing God’s messages imparted through others, and Davis interestingly adds some thoughts about the challenges of fear and pride (pages 46-47). This “active listening” to others is to be set alongside the need for regular meditation on scripture (Chapter 15), not mere uncritical proof-texting, which appears elsewhere in the book. Separately, Chapter 10 plays with the “beehive” imagery and the way hexagons fit together perfectly, an illustration of how a project should work, a line of discussion that concludes with this communitarian statement: “…an individual cannot save the world; however a swarm of BEEs in each city can rebuild areas, then blocks of areas, followed quickly throughout a city. Multiple cities make up a country. Multiple countries make up a region. Multiple regions make up the world” (page 104).

A different book might have taken some of these statements and developed them by placing them alongside (and sometimes in tension with) the thinking set out by other authors who have considered the place for enterprise within the Christian world-view. The reader is left to do this work for themself. For example, the rich and in my mind helpful concept of the vocation of the entrepreneur, as proposed by Davis, could have been explored within a more general discussion on vocational calling, and specifically the nature of work within God’s providence.

In a way, the most inspiring section of this book for me was Section 6 (Chapters 16, 17 and 18), which describes empirical research about the distinctiveness of Christian-led and Christian-inspired businesses. Such enterprises typically have greater productivity, staff loyalty, and general outperformance. In this regard, I found the story of Walker Mowers engaging, not least the way in which the owners and directors of this business deliberately attempt to tell the story of the company within the bigger context of the story of salvation history (page 155). An enterprise is thus no longer a means to an end (profit), but is part of an over-arching narrative that embraces God’s purposes. This theme alone could have been developed into a major piece of thinking that I believe would be incredibly timely and helpful for business in today’s world.

In sum, this is a “popular” rather than “scholarly” book. It is, in the main, an easy read with occasional thought-provoking nuggets. With rather less “prosperity gospel” and rather more theological reflection on the important themes that are hinted at, it would have been much improved upon.

“The Biblical Entrepreneur’s Experience” by S Leigh Davis was published in 2021 by River Birch Press (ISBN-13: 9781951561802). 260pp.

Edward Carter is Vicar of St Peter Mancroft Church in Norwich, having previously been the Canon Theologian at Chelmsford Cathedral, a parish priest in Oxfordshire, a Minor Canon at St George’s Windsor and a curate in Norwich. Prior to ordination he worked for small companies and ran his own business.

Edward Carter is Vicar of St Peter Mancroft Church in Norwich, having previously been the Canon Theologian at Chelmsford Cathedral, a parish priest in Oxfordshire, a Minor Canon at St George’s Windsor and a curate in Norwich. Prior to ordination he worked for small companies and ran his own business.

He chairs the Church Investors Group, an ecumenical body that represents over £10bn of church money, and which engages with a wide range of publicly listed companies on ethical issues. His research interests include the theology of enterprise and of competition, and his hobbies include board-games, volleyball and film-making. He is married to Sarah and they have two adult sons.