David Hebert – Deflating the Myths Surrounding Inflation

Subscribe to the CEME Substack

Inflation is a topic that plenty of pundits and talking heads have brought up on the news. For the non-economists, it might seem as if they do so ad nauseum. Despite its frequent coverage, however, few people understand why the U.K., like much of the rest of the world, generally accepts the idea that targeting two percent inflation is ‘good’ while inflation of any other number is ‘bad.’

Here, I want to provide some surface-level thoughts on these questions. While this will certainly not delve into the topic at the depth necessary to complete a graduate course in monetary theory, it should provide sufficient detail to enable meaningful and productive dialogues, which is ultimately what the world needs.

What is Inflation?

Milton Friedman once remarked that ‘inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon.’ What he meant by this is that inflation is caused when the amount (or quantity) of money increases relative to the amount of goods and services produced in an economy. In a dynamic economy characterized by economic growth and progress, inflation would occur when a central bank increases the money supply faster than the economy grows.

Is Inflation Bad?

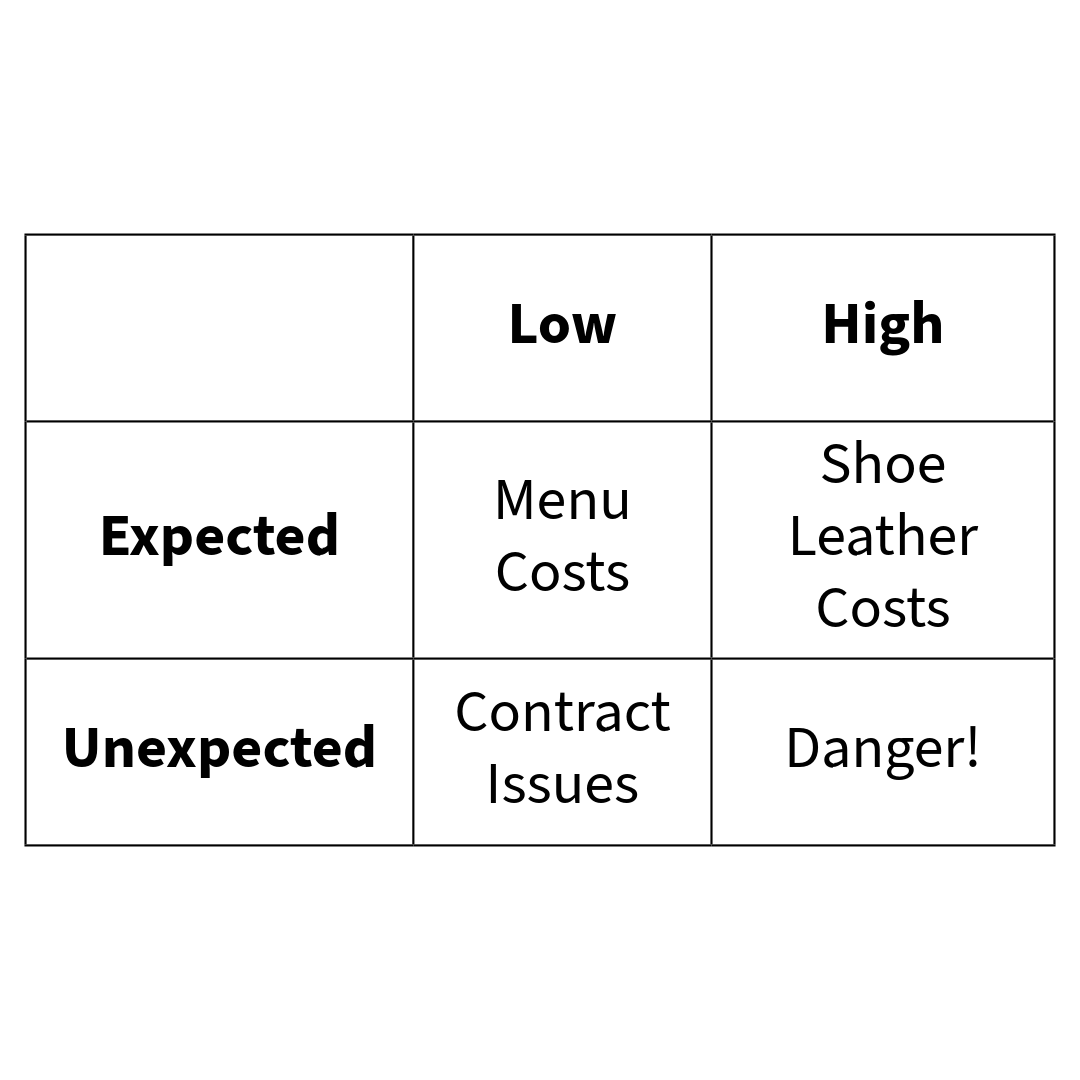

To address this question, it’s useful to think about inflation along two dimensions: 1) whether the inflation is low or high and 2) whether the inflation is expected or unexpected. I will not attempt to define ‘low’ or ‘high’ in this essay. Instead, I will simply defer to the reader’s judgement of the inflation rate in light of the following.

Expected and unexpected, however, are self-explanatory but carry with them implications that may not be intuitive. If inflation is fully expected, e.g. if the people expect 2% inflation over the coming year and the inflation rate is 2%, then the inflation will be relatively benign as buyers and sellers writing contracts lasting the duration of the year will build the anticipated 2% inflation rate into their negotiations. However, if people expect 2% inflation and the inflation rate differs from this, then there will be some unexpected inflation.

Thinking along these two dimensions allows us to put these into a matrix, which I explain in further below:

Expected, Low

In situations where inflation is both low and expected, the problems are relatively benign. One that was an issue in yester-year is referred to as ‘menu costs.’ Here, the changing prices will cause stores (particularly restaurants) to have to change their stated prices. In a world of physical, paper menus and magazines, this means reprinting them and sending new magazines out to customers, which is costly.

This was exemplified in the U.S. with Subway restaurants, which had a promotion called the ‘Five Dollar Footlong’ where any full sized sandwich with standard toppings (i.e. no ‘extra meat/cheese’) cost $5. The jingle from the commercial was so catchy that Subway had a very difficult time keeping up with customers’ expectations as inflation increased the nominal cost of producing a sandwich. To keep up with it, Subway initially reduced the amount of meat/cheese included per sandwich. Then they excluded certain sandwiches from the promotion. Eventually, they even shortened the sandwich. However, there is only so much ‘shrinkflation’ that they could get away with and they were forced, eventually, to abandon the promotion altogether in 2014, much to the ire of devoted customers.

Expected, High

In situations like this, we see all sorts of seemingly-wild behavior that is rendered intelligible through understanding economics. One such behavior has to do with employees. When nominal prices are rising quickly (even throughout the course of the day!), employees will demand to be paid more frequently so that they can spend their earnings before the value of the money drops even further. Because of this, they will take frequent trips to the bank or to stores, thus wearing down their shoes more quickly, earning the moniker, ‘shoe leather costs.’

Unexpected, Low

Unexpected inflation, even if it is low, can cause problems for long-term contracts. For example, suppose that everyone expects 2% inflation but the inflation rate is actually 3%. In this instance, money in the future is worth less than even the people entering the contract expected. This will mean that sellers will be harmed and buyers will be advantaged as they are paying with money that is worth even less than they had anticipated.

If the inflation rate were actually 1% instead, then money will be worth more in the future than both parties anticipated. This means that buyers will be harmed as they are giving up something more valuable than they expected and sellers will be advantaged as they are getting something more valuable.

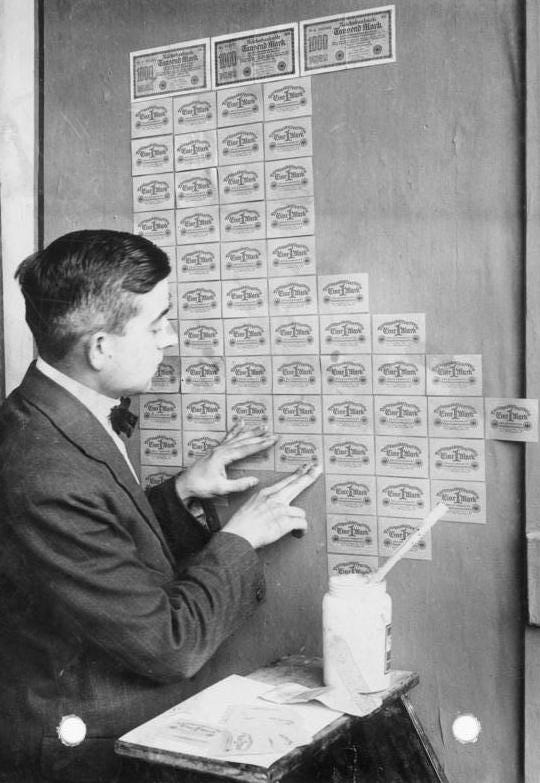

Unexpected, High

Often, this is a sign of a country’s collapse, as they find themselves having to inflate the money supply so quickly as to render money effectively meaningless. Why they get trapped in a situation like this is a topic for another day, but the short version of it is that the central bank/government faces two options, neither of which is good: hyper-inflate the money supply and delay their economy’s ultimate collapse in the hopes that things will get better or cease inflating the money supply and cause its immediate collapse. Neither of these options are ‘good’ and often portend disaster.

Inflation Targets

One might ask a simple question: why have an inflation target to begin with? For starters, having a target gives central banks a sort of benchmark to judge whether they have gone ‘too far’ or ‘not far enough’ in their operations. But why have a target that is different from zero? After all, if inflation only imposes costs, then it would seem that targeting zero inflation would be prudent.

First, there was a little problem in the U.S. in 1929 called ‘the Great Depression.’ While there is much debate as to what caused it, one factor that is generally accepted is that banks had loaned out too much money too quickly over the course of the 1920s. As a result, their cash balances were severely depleted. Without sufficient cash on hand, banks could not meet the withdrawal requests of their patrons. One way to make sure that banks always have enough money on hand is for central banks to make sure that they always have a little bit too much money on hand, but this leads to inflation.

Second, the very nature of a ‘target’ is that it can be and often is missed. By setting a target above zero-percent, central banks ensure that their errors will not result in negative inflation or ‘deflation.’

With low, expected, and consistent inflation, however, many of the problems above disappear. Indeed, even the ‘menu costs’ problem has all but disappeared thanks to the rise of online shopping and the fall in television displays as menus in restaurants, which can be updated instantly.

In fact, there may even be some benefits to low inflation. John Maynard Keynes, for all his problems, did recognize one fact that seems particularly important: some prices tend to be ‘sticky’ or ‘slow to adjust,’ especially in the downward direction. One important price that fits this description would be wages. People just do not like to see their salaries decrease. In fact, people often feel better if they get a raise in their nominal paychecks even if their new paycheck is able to purchase less (due to inflation) than their previous paycheck.

For this reason, having consistent inflation can be helpful for employers, who can lower someone’s real wages without reducing their nominal wages. While this is certainly lamentable and we do not wish to see it happen to anyone, it does happen in e.g. industries that are in decline.

Incidentally, this is also where the 2% target rate comes from. 2% is most certainly ‘low’ and if it is expected, well, then it will be relatively benign on the economy as a whole. There is nothing magical about the number two here. It’s not so high that it would cause a truly noticeable increase in nominal prices year-over-year but it is high enough that to allow for real price decreases despite increasing nominal prices. In the end, low, expected, and consistent inflation may impose some costs on society but it may also provide some benefits. As for whether a central bank can deliver low, expected, and consistent inflation is a question that is up for debate.

David Hebert is a Senior Research Fellow at the American Institute for Economic Research. His work can be found at www.davidjhebert.com.

Follow him on X: Dave_Hebert

Image: Germany, 1923: During hyperinflation, banknotes had lost so much value that they were used as wallpaper, being much cheaper than actual wallpaper.

Bundesarchiv, Bild 102-00104 / Pahl, Georg / CC-BY-SA 3.0, reproduced from Wikimedia commons under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Germany licence.