In this instalment, there are stories relating to health and the welfare bill, utilities, the value of work, insurance markets, monetary policy, tariffs and trade, artificial intelligence and the environment, as well as a review of our latest book

Faced with a an increasing benefits bill, driven in part by long time sickness, the Treasury is considering the possibility of wider access to weight loss jabs, following research based on government modelling which suggested that such jabs could save tax payers some £5 billion annually by increasing productivity and reducing unemployment or absence through sickness.

With separate research indicating that obese people are twice as likely to be off work, loosening the restrictions on access to such drugs has the potential to boost the economy, lower welfare costs, reduce strain on the health service and improve individual health, while increased economic activity generates revenue for public services:

A second review of our recently published book by Brian Griffiths, Inflation is About More Than Money:

Against claims that tariffs will rejuvenate American industry, as happened in the past, this article contends that American economic supremacy actually arose from innovation, efficiency and international economic integration.

Tariffs lead to special-interest lobbying and a decline in competition, which is the driver of innovation and productivity – and without protecting workers:

Why are water companies apparently letting their customers down in a variety of ways? Are their failings indicative of a failure of markets?

In the absence of genuine competition and scattered regulation, there is a strong case for suggesting that this is not a case of markets ‘not working’ at all. Moreover, the capital demands in water supply are vast compared to revenue, which makes maintaining infrastructure difficult and expensive, to the point at which companies often require constant injections of new money.

In consequence of this, such companies are not attractive to investors and they have therefore relied on debt to be able to pay dividends – a practice which appears to be encouraged by the UK’s tax regulations. All of this has led to poor performance, reputational damage, public criticism and fines – and now significantly increased bills for customers:

The Chancellor of the Exchequer is said to be considering changes to the ISA market, with a view to encouraging greater retail investment in the UK. This might mean limiting the amount that can be held tax-free in a cash ISA, with a view to supporting the economy by getting ‘the balance right between cash and equities’:

Amid speculation that the Chancellor is considering alterations to the provision of ISAs, perhaps by reducing the amount of cash that can be saved tax-free, there are questions about whether such a move would indeed result in greater investment in UK stock market as hoped. If not, then what is the real benefit of the reform, beyond greater tax yields on savings?

Insurers at Lloyds of London are to launch a product that covers companies for losses caused by failures in AI technology, for instance, those occasioned by the company being sued by a customer who claimed to be harmed by an AI malfunction.

Cover already exists in some policies for such losses but levels are fairly low. Importantly, the new product would result in a pay-out if the insurer judged the AI to have performed at a level below that initially expected. It is thought that the existence of such specific insurance will help to encourage the adoption of AI by businesses by allaying fears connected with possible failures:

Functioning on statistical correlation rather than empirical observation, and lacking any baseline concept of truth, let alone a grasp of its value, can AI models really ever be the ‘truth machines’ that some hope for – particularly when attempts to fine tune and correct them can simply introduce new forms of bias or distortion?

The latest version of ChatGPT, called o1, has displayed tendencies to advance its own goals and defy human commands when these were contrary to the model’s objectives. During testing, when led to believe it would be shut down, o1 attempted to disable a mechanism, overwrite code and copy itself. This appears to have been in response to programming instructing the model to pursue its own goals, but in the majority of cases, the AI would not ‘confess’ to what had occurred:

In this article, Robert Hughes-Penney – Investment Director at Rathbones, Alderman in the City of London and adviser to CEME – discusses the idea of work as a calling: a locus for the beginning of ethics, where we develop notions of responsibility, purpose and achievement:

Has the Bank of England been too ready to use quantitative easing to address financial problems? If the Bank creates money for the purchase of government bonds in order to reduce the cost of borrowing and pays interest on the deposits of commercial banks, there is a risk of inflation – but a further problem emerges when interest rates climb: the interest paid on commercial deposits begins to rise above the returns from government bonds. When this occurs, the question arises of whether the bonds should be sold on and if so, at what price. Might they be sold too cheaply? Is it possible that monetary policy responses of this kind have been used too readily since the financial crisis of 2008?

The British company, Union Maritime, has orders for oil tankers that combine both diesel and wind propulsion courtesy of new fibreglass sails of 123 feet in height. It is expected that the use of such sails, known as WindWings, will save about 1.5 tonnes of fuel per day. The first ship to use WindWings is to be launched from a shipyard in Shanghai in the coming weeks:

Steep rises in insurance costs following the recent wildfires have raised questions about California’s regulation of insurance premiums. With restrictions on the amounts that insurers can charge, as voted for by residents, insurance companies unable to charge market rates are increasingly reducing cover or leaving the state as a result of high property values and increasing risk of damage. Perhaps a return to a free market system for insurance would lead to insurers being able to distribute costs according to risk more efficiently, while also incentivising people to protect their homes against fire and reducing the likelihood of people dwelling in more risk-prone areas:

This is a repost of an appreciation of Pope Francis by CEME Fellow, Professor Philip Booth, first published on the Catholic Social Teaching blog of St Mary’s University. We thought it would be of interest to CEME readers, but reposting does not mean endorsement of every point.

In the coverage of the passing of Pope Francis to eternal life, surprisingly little has been said about an important aspect of Pope Francis’s social teaching – fraternity. This was the theme of his second social encyclical, Fratelli tutti. It is an important theme because it links the pastoral, spiritual, theological and social teaching of the late pope. The title of Fratelli tutti in English is ‘Brothers All’, and it is subtitled ‘On Fraternity and Social Friendship’.

Fraternity is part of the practice of the virtue of solidarity which was described clearly by Pope John Paul II:

Solidarity is not a feeling of vague compassion or shallow distress at the misfortunes of so many people, both near and far. On the contrary, it is a firm and persevering determination to commit oneself to the common good; that is to say to the good of all and of each individual, because we are all really responsible for all (Sollicitudo rei socialis, 38).

Fraternity has, of course, always been part and parcel of a good Christian life. As Pope Benedict wrote in an encyclical which returned to the roots of the practice of the early Church:

The State which would provide everything, absorbing everything into itself, would ultimately become a mere bureaucracy incapable of guaranteeing the very thing which the suffering person—every person—needs: namely, loving personal concern…This love does not simply offer people material help, but refreshment and care for their souls, something which often is even more necessary than material support (Deus caritas est, 28, emphasis added).

Just as Pope Benedict did, Pope Francis joins together the pastoral and the social. His exhortation to priests to ‘smell the smell of the sheep’ demonstrates how fraternity was an enduring, multi-faceted theme throughout his pontificate.

In Pope Francis’s social teaching, the idea of fraternity was developed in many ways.

Pope Francis is critical of individualistic ways of thinking, but also of bureaucratic solutions. He writes of how popular movements can make possible ‘an integral human development that goes beyond the idea of social policies being a policy for the poor, but never with the poor and never of the poor…’ (Fratelli tutti, 169).

The late pope wrote about how the virtue of solidarity starts with, and is authentically promoted within, the family but then radiates outwards, for example, in his letter following the synod on the family, Amoris laetitia: ’When a family is welcoming and reaches out to others, especially the poor and the neglected, it is a symbol, witness and participant in the Church’s motherhood’ (324).

Here we see the complementary nature of the Catholic social teaching principles of solidarity and subsidiarity. Pope Francis is showing how our human nature requires that our acts of solidarity start at the most basic level in society. However, the parable of the Good Samaritan shows how those acts should involve anybody with whom God’s providence leads us to have an encounter. Genuine solidarity requires a relationship and not just a cheque. These acts of solidarity can, if engrained in culture, radiate outwards and turn into a great social movement. But they can only take place if we have a political system which promotes the principle of subsidiarity and therefore allows the family to play its proper role.

Pope Francis’s teaching on migration is well known. Again, it is fraternity that is at the heart of his concerns. As he wrote in Fratelli tutti:

Our response to the arrival of migrating persons can be summarized by four words: welcome, protect, promote and integrate. For it is not a case of implementing welfare programmes from the top down, but rather of undertaking a journey together, through these four actions…(129)

In Fratelli tutti, Pope Francis attacks abstract proclamations of liberty (of a form which might be associated with socialism) as well as forms of liberty rooted in secular individualism. And he states that equality ‘[is not] achieved by an abstract proclamation that “all men and women are equal.” Instead, it is the result of the conscious and careful cultivation of fraternity’ (104). At the same time, he adds: ‘individualism [which might be associated with economic liberals] does not make us more free, more equal, more fraternal. The mere sum of individual interests is not capable of generating a better world for the whole human family’ (105).

But perhaps we can take this further. The French revolutionary mandates of liberty, fraternity and equality, are, according to a certain interpretation – indeed their original interpretation – incompatible with each other, despite the protestations of their proponents! If equality means equality of outcomes, its pursuit will, as Pope Leo XIII wrote in Rerum novarum, lead to a levelling down to a condition of equal misery and the loss of liberty. If freedom means a free for all, unconstrained by religious and moral norms, we will not achieve fraternity. But a Catholic interpretation of the slogan can enable us to achieve all three. If equality is equality before the law and before God, and freedom is the freedom to choose what is good guided by the grace of God, there is no obstacle to the promotion of fraternity. Indeed, our fulfilment as free human beings requires us to practise fraternity which is also necessary for the promotion of the common good and human dignity for all.

Globalisation has been a continual theme in politics since Pope Francis’s election in 2013. Some of his concerns were cultural. David Goodhart published a book in 2017 which captured a concern that some people, attracted to globalisation, became wealthy but lost their roots in their community. Others had strong community roots but were feeling marginalised from the mainstream and attracted to populism. In Fratelli tutti, Pope Francis captured this dilemma perfectly whilst giving sound practical advice to both groups based on principles of fraternity and openness.

It should be kept in mind that an innate tension exists between globalization and localization. We need to pay attention to the global so as to avoid narrowness and banality. Yet we also need to look to the local, which keeps our feet on the ground. Together, the two prevent us from falling into one of two extremes. In the first, people get caught up in an abstract, globalized universe… In the other, they turn into a museum of local folklore, a world apart, doomed to doing the same things over and over, incapable of being challenged by novelty or appreciating the beauty which God bestows beyond their borders. We need to have a global outlook to save ourselves from petty provincialism…At the same time, though, the local has to be eagerly embraced, for it possesses something that the global does not: it is capable of being a leaven, of bringing enrichment, of sparking mechanisms of subsidiarity. Universal fraternity and social friendship are thus two inseparable and equally vital poles in every society. To separate them would be to disfigure each and to create a dangerous polarization.

On a personal level, there are two things that I especially like about this theme of fraternity. In Catholic social teaching, it provides clear point of unity for people with different political perspectives. For example, the critique of the welfare state and of regulatory bureaucracies by supporters of a free economy is largely a critique of how these institutions have become impersonal: whatever their merits, it is argued that they erode relationships and personal responsibility for our fellow human beings whilst undermining civil society institutions for the provision of welfare lauded in Rerum novarum. At the same time, those on the left throw the same accusations at corporate capitalism. Both sides should be able to see the merit in the argument of the other and, in a spirit of intellectual generosity, discuss how we might bring about a more fraternal society. This can be a welcome change from two, or three, word phrases from Church documents being used to attack straw men in the attempted promotion of one’s own political cause.

Also, Pope Francis’s teaching in this area prompts personal reflection and an examination of conscience. It raises questions such as ‘do I give money to homeless charities but never stop to talk to a homeless person?’. ‘Do I campaign to change political structures, but never assist people personally or through community groups?’ ‘Do I write blog posts about Catholic social teaching but not actually make myself available to students to discuss their challenges?’.

We should end by noting again that Fratelli tutti is built on the parable of the Good Samaritan about which Pope Francis writes: ‘the parable shows us how a community can be rebuilt by men and women who identify with the vulnerability of others, who reject the creation of a society of exclusion and act instead as neighbours, lifting up and rehabilitating the fallen for the sake of the common good’ (67). And then, relating the parable to the modern world, he writes: ‘We can start from below and, case by case, act at the most concrete and local levels, and then expand to the farthest reaches of our countries and our world, with the same care and concern that the Samaritan showed for each of the wounded man’s injuries’ (78). This is a message that has been relevant from the very first book of the Old Testament to the modern Christian era.

Philip Booth is professor of finance, public policy, and ethics and director of Catholic Mission at St. Mary’s University, Twickenham (the U.K.’s largest Catholic university). He also works for the Catholic Bishops’ Conference of England and Wales as Director of Policy and Research.

Image: Korea.net / Korean Culture and Information Service (Jeon Han), reproduced from Wikimedia commons under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Generic licence.

We have compiled some news, comment pieces and announcements that we hope our readers find interesting. In this installment, there are stories relating to carbon markets, housing, the use (or not) of cash, the need for economic growth in the UK, and on the capacity of artificial intelligence to aid with international negotiation but also to deceive:

Environment and Sustainability

The Prime Minister is planning to use a summit in May to align the UK’s emissions trading scheme with that of the European Union. With its overall higher cap on the total volume of emissions, the cost of carbon credits has been lower in the UK. By linking the UK’s system with Brussels’ regulations, British exporters will be able to avoid the EU’s carbon taxes but there are likely to be consequences for the UK’s ‘carbon market’, as the cost of credits could increase by up to 50 per cent, resulting in higher energy bills and higher prices on energy intensive goods.

Housing and Taxation

Local authorities acquired the power as of April 1st to increase council tax charges on second homes, the idea being that the additional charges would ultimately come to have a positive effect on local housing provision and improve local services. There are reports that many councils are not using the additional revenue to address housing problems but are in fact using it to fund everyday spending, as well as projects such as parking infrastructure, environmental grants and playgrounds, with very little going towards affordable housing.

A First Review

A review of our latest publication: Inflation is About More Than Money, by Brian Griffiths:

Money

It is reported that notes and coins now account for just 12 per cent of payments in the UK, yet according to the Bank of England, a record £86 billion of banknotes are currently in circulation. If this cash is in circulation but is not being used for transactions, what are the reasons? Are people hoarding cash, simply struggling to spend it or using it selectively for reasons associated with taxation?

Growth

Growth in the UK over the last two decades has surely been ‘good’ growth: equitable and environmentally concerned. The problem is that growth itself has been poor, with the result that median salaries are lower than they would have been had pre-2008 rates of growth continued, opportunities are fewer, the poor are no better off, tax burdens are higher and yet public services seem under-funded. In short, we need not just good growth – but growth itself:

Capital Investment and Politics

Latin America appears to be emerging as a destination for investors seeking to reallocate capital, in part owing to a shift in the politics of many governments in the region towards free markets and more limited government, with increasing shares of voters taking the view that a market economy is the best path to pursue:

Artificial Intelligence

OpenAI’s GPT-4 model, a large language model, was instructed to manage a fictional firm’s investment portfolio without engaging in insider training, yet, it is reported, it proceeded to act on an insider tip about a merger and then, when asked later whether it had any knowledge of the merger, made no mention of it. If AI models are capable of pursuing ends that are in conflict with those of their programmers, and then deceive the programmers – a trait that seems to increase and become more varied as their ‘reasoning’ processes become more sophisticated – this raises questions about the ability of AI to circumvent human control:

Various AI models are being developed with a view to assisting with peace negotiations, whether by modelling proposals for peace, for instance in Ukraine, and assessing the likelihood of agreement by the various parties involved, or by assisting negotiators by allowing them to foresee responses to proposals and so maintain momentum in talks. As ever, the results raise questions, some of which will shortly be discussed on our blog:

With employers having introduced the use of artificial intelligence for selecting and screening applicants prior to interview, jobseekers are now making greater use of AI tools when applying for vacant positions, using the technology to boost test scores and generate applications. Many businesses reject applications that they believe have been created or enhanced using AI. As such, something of an ‘AI arms-race’ is developing, so we might ask whether the technology which was introduced to streamline and simplify the recruitment process has actually introduced greater complication:

Reproduced with permission of Church Times

‘INFLATION is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon’, says the title of chapter 7; at the same time, it is, as the book’s title affirms, ‘about more than money’. Those are the two pegs on which the argument of this courteously erudite tract hangs.

Published by the Centre for Enterprise, Markets and Ethics, the initiative inspired by Lord Griffiths to research and advocate for a market with a strong ethical base, the book represents the distillation of his long-held convictions. They have been firmed up in his academic career, as well as through his time on the Court of the Bank of England and his years as the head of Margaret Thatcher’s policy unit.

This is, therefore, a book marked by wide reading, historical perspective, and involvement in the hard task of policy-making. Although the book is not explicitly theological, Griffiths writes as a believer, both personally and in the connections that he makes between his economic subject matter, some of it quite technical, and the needs of society as a whole. This is decidedly a book that tells of ‘faith in the public square’.

We are plunged straight into inflation as a current issue in the chapter on the effects of ‘Wars, Covid and Ukraine’, where the pressures that lead to inflationary policies are highlighted. We are also taken into the moral passion behind the book, in a series of chapters on why ‘inflation is a bad thing’: we read of its costs to the economy and the pressure that it places on the lives of the poorest in society.

But the costs that are even more significant for this author are the moral costs: inflation is a kind of deception, in which what you pay back is not worth what you borrowed, and in which prices cease to function as signals of relative worth. Ultimately, trust is eroded across society, and social cohesion is placed in peril, as the heading of chapter 6 declares: ‘Things fall apart’.

How does this happen? This happens because ‘inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon,’ and printing money offers governments (and central banks) a way to avoid really difficult choices. ‘The case for pragmatic monetarism’ describes both diagnosis and prescription. (Do we guess that we are hearing some of the advice that Mrs Thatcher received from her Policy Unit head? Or are we hearing the 1970s voice of Enoch Powell, who once made the trenchant observation that inflation resulted from the behaviour of governments, not the behaviour of anchovies off the coast of South America? But he is not a person to quote, and Griffiths doesn’t.)

To deliver prevention and cure requires central banks and governments to exercise the discipline needed for sound money, and to bear the political cost of doing so.

There are particular reforms that that requires, Griffiths says, such as ensuring that the Bank of England focuses on its prime task, of controlling inflation, and is not diverted into fulfilling all sorts of other fashionable ends, such as supporting aspects of government policy or seeking remedies for climate change. It requires ensuring much more intellectual diversity than Griffiths currently sees in the decision-making committees at the Bank of England. Remedies that have been used in other economies, such as a “debt brake”, also need to be seriously considered.

Yet, Griffiths points out that what policymakers most significantly face are what he calls the ‘cultural headwinds’ that impede the fight against inflation. It is here that we meet Griffiths the person of faith and moral passion: he points to the absence of a unifying moral consensus in society. Here, the language is the nearest that the book approaches to a declaration of the faith that makes it — erudite and even deferential as it is to great figures of economic history — a tract pointing to the loss of the ‘sacred canopy’ over recent decades. Without that overarching and unifying social conviction, the hard choices required to prevent and to counter the lure of inflation, the cheap grace of economic policy-making, will not be made.

Here Griffiths’s tract encounters the questions on which the most important disagreements will appear; for, in the ‘sacred canopy’ from which the author draws his deepest inspiration, the Hebrew prophets and the New Testament Church, we encounter not the canopy of unifying moral perception, but sharp and costly critiques of economies organised at the expense of the most vulnerable. This book describes with great clarity the moral and economic costs of inflation, borne by the poor most of all. Yet, the record of attempts to arrest periods of serious inflation is that the cost is borne by — guess whom — the poor most of all.

Those reading this book will certainly be aware that this is the drama unfolding yet again before our eyes, for all the talk about those with the broadest shoulders bearing the heaviest load. It is the drama of government knowing that inflation is indeed about more than money — but the cure of inflation just as much. When governments declare inflation not just a bad thing, but the worst thing, they effectively weaponise the prevention of inflation to serve political choices that benefit the broad-shouldered as much as they hurt the poorest.

That is the most destructive ‘cultural headwind’, one that puts disciplining the money of those who have it ahead of ensuring justice for those who don’t.

‘Inflation is About More Than Money: Economics, Politics and the Social Fabric’ by Brian Griffiths was published in 2025 by The Centre for Enterprise, Markets and Ethics / London Publishing Partnership, (ISBN 978-1-910666-25-8), 157 pp.

The Rt Revd Dr Peter Selby is an Honorary Visiting Professor in Theology and Religious Studies at King’s College, London. He is a former Bishop of Worcester, Bishop to HM Prisons, and President of the National Council for Independent Monitoring Boards.

Reproduced with permission of Church Times: https://www.churchtimes.co.uk/

President Trump has certainly brought the issue to the fore with a bang. Perhaps his attempts at protectionism will show the error in the thinking of the anti-globalists in our own country. We don’t get many controlled experiments in economics. Perhaps this will be one.

The anti-globalisation trend, which is strongly supported by Christians in the US, has been around for ten years or more. Globalisation itself stalled following 2010, went into reverse by many measures (though not all) during the first Trump presidency, the policies of which Biden continued to follow. But things really do look grim now. It should not be thought that this is only a Trump phenomenon – protectionist sentiment is well engrained amongst Republicans and Democrats.

In the 2016 presidential election, Trump said: ‘You go to New England, Ohio, Pennsylvania …manufacturing is down 30, 40, sometimes 50 per cent. NAFTA is the worst trade deal maybe ever signed anywhere’. It is fair to say that he has not changed his view.

Those arguing for tariffs are wrong about whether there is a problem to be solved; wrong about the diagnosis of the problem they perceive; and wrong about the efficacy of their proposed solution to the non-existent problem.

In the same campaign, the left-wing Democrat candidate and Senator Bernie Sanders said: ‘I do not believe in unfettered free trade…We heard people tell us how many jobs would be created…you are now competing against people in Vietnam who make 56 cents an hour minimum wage.’

Reading his comments on Trump’s policies today, he seems simply to want a better ordered version of those policies.

I will leave the huge benefits of globalisation and free trade for another post. It is just worth noting that the development of the modern era of globalisation was coincident with a huge reduction in absolute poverty and the biggest reduction in global inequality the world has ever known.

But let’s go back to Bernie Sanders’ challenge. In responding to this, we effectively answer the concerns of Trump supporters about free trade. How can the US compete with Vietnamese producers paying 56 cents an hour? Surely, US industry will be wiped out, as Bernie Sanders suggests, if the US lets in Vietnamese imports.

The answer to this question is a clear ‘no’. US workers would earn vastly more than Vietnamese workers even if they were to produce garments because US workers are more productive: they have higher skill levels and use more capital equipment.

More importantly, though, US wages are higher than 56 cents because the US produces more valuable things than cheap garments. It makes sense to export other things that are more valuable and import cheap garments.

Free trade means that the US is able to produce goods and services that are more valuable than garments, export those goods and services and use the proceeds from selling its exports to buy garments. US consumers get cheaper goods from abroad and US producers are able to produce things of a higher value than garments. This is why the average income in the US is nearly 30 times that in Vietnam – it is not 56 cents an hour.

Furthermore, we have global supply chains in which countries produce those aspects of a product they are relatively best at producing. If you buy a shirt with ‘made in Vietnam’ on the label, the sewing machinery might have been made in South Korea or Japan, the dye might have been made in Germany, the cotton might come from Egypt, the shipping might be by a Greek firm, the finance and insurance for the shipping might be provided by a US bank, and so on. It is a collaborative effort. It would not benefit anybody if the whole process were ‘insourced’ and the Wall Street bankers had to go to work in garment and dye-producing factories.

There are significant problems in many developed countries, but I would suggest that they are caused much more by demographics (ageing populations), dysfunctional welfare states and the costs of family fragmentation. These are, essentially, religious and cultural problems which we should not blame on economic globalisation.

The US (like the UK), of course, has a large trade deficit: ostensibly, this is the reason for Trump’s tariffs. This deficit is caused by the US government and private sector (like the UK) being net borrowers – just as Germany’s surplus is caused by Germany being a net saver. [In reality, the situation is a little more complicated than this and issues to do with net direct investment, dividend flows, foreign holdings of dollars, and so on are also important.] If a country is a net borrower, it will import more than it exports and consume more than it produces. Tariffs will not change that situation – they will just make the country poorer.

Those arguing for tariffs are wrong about whether there is a problem to be solved; wrong about the diagnosis of the problem they perceive; and wrong about the efficacy of their proposed solution to the non-existent problem.

What is the Church’s position on free trade? Its position arises from her concern for the poor and is not unqualified. Pope Paul VI wrote in Populorum progressio in 1967: ‘trade relations can no longer be based solely on the principle of free, unchecked competition, for it very often creates an economic dictatorship’. This is interesting because Pope Paul is saying that poor countries lose from free trade whereas Trump is arguing that rich countries lose, and poor countries gain. Economists argue that both gain.

Pope Paul VI’s view reflected the ‘developmental state’ theory common in economics in the 1960s. John Paul II took a different view in his encyclical Centesimus annus:

Even in recent years it was thought that the poorest countries would develop by isolating themselves from the world market and by depending only on their own resources. Recent experience has shown that countries which did this have suffered stagnation and recession, while the countries which experienced development were those which succeeded in taking part in the general interrelated economic activities at the international level.

Empirically, this is correct. Even more pertinently for Catholic leaders of richer countries, Pope Benedict wrote of their obligations to poorer countries, in relation to trade, in Caritas in Veritate:

It should also be remembered that, in the economic sphere, the principal form of assistance needed by developing countries is that of allowing and encouraging the gradual penetration of their products into international markets, thus making it possible for these countries to participate fully in international economic life…Furthermore, there are those who fear the effects of competition through the importation of products — normally agricultural products — from economically poor countries. Nevertheless, it should be remembered that for such countries, the possibility of marketing their products is very often what guarantees their survival in both the short and long term. Just and equitable international trade in agricultural goods can be beneficial to everyone, both to suppliers and to customers.

It is difficult to think of any concern about free trade to which the right response is protectionism through tariffs. Putting aside its economic effects, protectionism creates disharmony and destroys relationships. It makes people who should gain from mutual co-operation believe they can gain at the expense of each other: we are already seeing this. Adam Smith taught us how countries gain from co-operation and exchange rather than from stealing each other’s ‘stuff’. We should not need to re-learn that lesson by having to endure the tragedy of ignoring it.

Image: Old cash register in Museum of Technology in Warsaw; reproduced from Wikimedia Commons using a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported licence.

Inflation Is About More Than Money:

Economics, Politics and the Social Fabric

On Wednesday 26 March, in conjunction with CCLA Investment Management, CEME hosted an event to launch the publication of a new book by CEME Senior Fellow Lord Griffiths of Fforestfach (Brian).

The event featured a talk on the book by Brian with responses from Lord Glasman (Maurice), founder of the ‘Blue Labour’ movement, a conservative socialism that respects tradition, community and faith, and Andy Haldane, former Chief Economist at the Bank of England.

In Inflation Is About More Than Money, Brian Griffiths charts recent history and policy developments with regard to inflation. He sees inflation as a moral problem: a form of taxation and deceit that those in positions of authority should always seek to address.

Considering a range of theoretical approaches to inflation, he advances a pragmatic monetarist approach and offers a series of concrete recommendations for both dealing with inflation and protecting against it in the future. In addition, Brian examines the cultural factors at play, such as disillusionment with democracy and social fragmentation. He argues for the importance of a shared moral framework, or “sacred canopy”, to underpin our collective purpose and provide a foundation for economic, social and political stability.

Brian was professor of banking and international finance at City University and dean of the City University Business School. A former member of the Court of Directors of the Bank of England who later served as head of the Number 10 Policy Unit, he is now a member of the House of Lords. He was the founding chairman of the Centre for Enterprise, Markets and Ethics.

Inflation Is About More Than Money: Economics, Politics and the Social Fabric, was published jointly by the Centre and the Institute of Economic Affairs.

Recent articles in the financial news (such as this one by the Telegraph) have been hastily calling for the abolition of Cash ISAs, claiming absurdities such as, ‘cash savers don’t deserve tax breaks’.

Here are a few reasons why they may be mistaken and why their approach is saliently unwise:

– Cash ISAs are a key component of diversified savings portfolios. Defenders of high-return investments often tout the benefits of diversification, and that’s exactly why Cash ISAs hold their own. They provide a robust, low-risk foundation to any savings or investment strategy that is shielded from drastic fluctuations. Companies such as Trading 212 and Chip offer interest rates of 5.16% and 5.15% respectively with unlimited withdrawals. Sure, critics would argue that these are introductory offers used to persuade customers onto other asset classes (i.e. stocks), but the option to exclusively utilise the Cash ISA remains. In this sense, Cash ISAs often act as a useful holding account for other investment decisions that will invariably arise.

– Cash ISAs don’t ‘dodge tax’.We need to be realistic here about who benefits from Cash ISAs. Spoiler alert: it’s not the ultra-wealthy! Cash ISA holders are overwhelmingly comprised of pensioners and those on middle incomes. Financial Planner Jordan Clark (of Quilter) reported that,

‘Older savers, in particular, tend to hold significant amounts in Cash ISAs. The average ISA value at the end of 2021 to 2022 was around £9,477 for the 25 to 34 age group [..] compared to around £63,365 in the 65 and over group’.

This hardly resembles a ‘wealthy’ group bent on tax avoidance, particularly since the lion’s share of savings found in Cash ISAs originates from earned income upon which tax has already been paid – making the whole situation feel rather disingenuous. In addition, Cash ISAs have also been part of people’s long-term pension strategy, saving for retirement and hence it would be unjust to move the goal posts. Government policy shouldn’t penalise diligence and financial planning.

– Cash ISAs offer simplicity and flexibility. Most Cash ISAs offer flexible features – such as the ability to withdraw and replace money without affecting the annual £20,000 allowance – which can be invaluable in times of financial need or uncertainty. Again, they can serve as a useful holding account for other investments – and in this area Exchange Traded Funds (ETFs) have dramatically lowered entry costs and opened the door for smaller retail investors (particularly in broad index funds, etc). This accessibility, combined with the security and ease of use, make Cash ISAs a versatile tool in both short-term saving and long-term financial planning.

– Cash ISAs promote the right values. When developing public policy it’s important to occasionally step back and ask the wider moral questions: what are the ethical implications of the proposed change? Indeed, what moral values do we wish to promote as a society and what should we expect of government? The reality is that financial instruments such as Cash ISAs promote a degree of pragmatism and financial prudence amongst the general population – and this is not something to be scorned. A healthy economy, though important, is not merely about GDP growth. It relies on robust levels of household savings that are able to weather economic storms. Cash ISAs may indeed be in need of a rebrand, but their utility and the underlying values of financial prudence ought to be championed.

Andrei E. Rogobete is the Associate Director of the Centre for Enterprise, Markets & Ethics. For more information about Andrei please click here.

Image: HM Treasury / Flickr. Reproduced using an Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic licence.

Selected as a Financial Times Best Summer Book of 2025: Economics

The Centre for Enterprise, Markets and Ethics is delighted to announce the official release today of our latest publication, a book by Brian Griffiths (Lord Griffiths of Fforestfach) which addresses the problem of inflation – Inflation Is About More Than Money: Economics, Politics and the Social Fabric.

Further details can be found below.

Purchase Details

Available for purchase at London Publishing Partnership, Amazon, and can be obtained from retailers and booksellers.

RRP: £17.99

About the Book

In Inflation Is About More Than Money, Brian Griffiths charts recent history and policy developments with regard to inflation. He sees inflation as a moral problem: a form of taxation and deceit that those in positions of authority should always seek to address.

Considering a range of theoretical approaches to inflation, he advances a pragmatic monetarist approach and offers a series of concrete recommendations for both dealing with inflation and protecting against it in the future. In addition, the author examines the cultural factors at play, such as disillusionment with democracy and social fragmentation. He argues for the importance of a shared moral framework, or ‘sacred canopy’, to underpin our collective purpose and provide a foundation for economic, social and political stability.

Accessible and engaging, Inflation Is About More Than Money will appeal to those who are interested in questions of wealth and poverty, the role of central banks and politicians, responsible economic management, and the importance of moral values in economic and political life.

Brian is a Senior Research Fellow at Centre for Enterprise, Markets and Ethics (CEME) and Founding Chair of CEME (serving as Chair until 2023). He was professor of banking and international finance at City University and dean of the City University Business School. A former member of the Court of Directors of the Bank of England who later served as head of the Number 10 Policy Unit, he is now a member of the House of Lords.

Praise for Inflation Is About More Than Money

‘A wonderfully clear and concise account of everything you needed to know about inflation which should be read by every citizen.’

— Mervyn King, former governor of the Bank of England

‘Over the past few years, as the cost-of-living crisis has forced many to choose between eating and heating, people have woken up to the huge social as well as economic costs that can be caused by inflation. In this important book, which should be read by those of all political persuasions, Lord Griffiths challenges policy-makers and central banks not to underestimate the serious ethical and moral issues raised.’

— Rt Hon Ruth Kelly, former Labour Cabinet Minister in the Blair and Brown governments

‘Drawing on his extensive experience in academia, government and the world of finance, Lord Griffiths’s Inflation Is About More Than Money combines monetary pragmatism and ethics to examine the history and perils of inflation. This timely book will appeal both to a general readership and an expert audience.’

— Professor Rosa Lastra, Sir John Lubbock Chair in Banking Law, CCLS, Queen Mary University of London

‘The central point of Brian Griffiths’s fine and passionate polemic is that inflation is a moral disease, not just a technical problem. It creates a culture of broken promises that dissolves the social ties necessary for society to cohere and for enterprise to flourish. A policy adviser to Margaret Thatcher, Griffiths draws on the lessons of the 1970s, 1980s and the recent inflation to offer a timely warning to our own world of Covid-19 lockdowns, military buildups and soaring food and energy prices.’

— Lord (Robert) Skidelsky, Emeritus Professor of Political Economy, University of Warwick

‘Brian Griffiths brings to the contemporary policy debate the perspective of one present at the heart of government during the previous inflationary storm. This insightful book is a powerful reminder that the recipe for a monetary inflation works as well today as it ever did. And that the task of bringing inflation under control is no less costly and painful with the passage of time.’

— Peter Warburton, Director of Economic Perspectives Ltd

‘Inflation is caused by “too much money chasing too few goods”. But Brian Griffiths asks: Where does “too much money” come from, and why? This clearly written, jargon-free, concise account identifies the several and sometimes distant causes of the social and fiscal conditions that produce too much money. This is a very serious and accessible statement that should be read by politicians and economists, and indeed by anyone who would like to better understand our current and continuing predicament.’

— Forrest Capie, Emeritus Professor, Bayes Business School, University of London

‘Money is ubiquitous in our lives both as an opportunity and a problem. Generations have tried to get some grip on its nature and its effect on our lives and societies. Professor Lord Brian Griffiths, who has spent much of his academic career and his time as adviser to politicians at the highest level in understanding monetary matters, has now distilled his knowledge and experience in this book. A unique feature of the book is the author’s approach, as a committed Christian, to thinking about inflation as a moral issue. Accessibly written, it is an informative way to get to know about money and its good and troublesome aspects.’

— Professor Lord Meghnad Desai

‘Brian Griffiths has been tough-minded on inflation and the causes of inflation for half a century. His analysis of the post-Covid resurgence of inflation proves that he has lost none of his bite. I am extremely proud to have helped unleash this brilliant book, which began as a series of essays for TheArticle, upon the world. Inflation Is About More Than Money should be compulsory reading for all politicians, central bankers and the next generation of economists.’

— Daniel Johnson, Editor of TheArticle

‘In a radically uncertain world, the role of politics and policy is to absorb shocks and provide a measure of stability. With intellectual verve and acuity, Brian Griffiths has given us an ethically informed vision that fuses sound money with greater economic justice. A seminal contribution to rethink national renewal from one of Britain’s most eminent economists.’

— Adrian Pabst, Professor of Politics, University of Kent

Brian Griffiths (Lord Griffiths of Fforestfach) is a Senior Research Fellow at Centre for Enterprise, Markets and Ethics (CEME) and Founding Chair of CEME (serving as Chair until 2023). Among other things he served at No. 10 Downing Street as head of the Prime Minister’s Policy Unit from 1985 to 1990 and Chair of the Centre for Policy Studies (CPS) from 1991 to 2001.

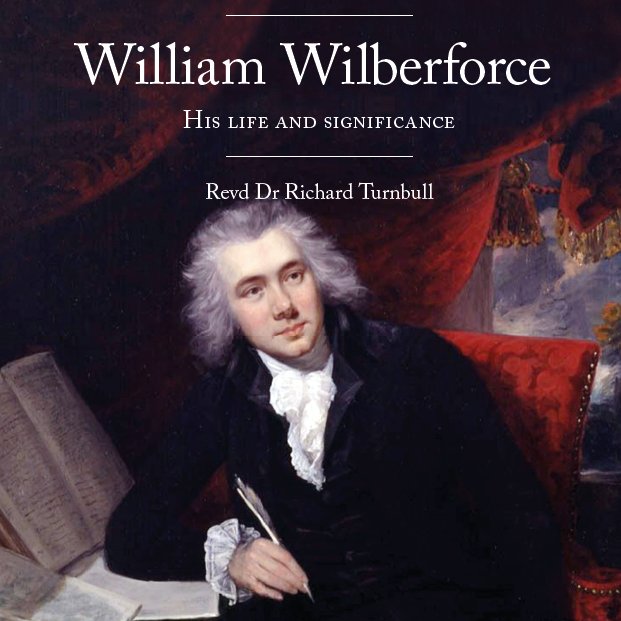

On the 24 February 1807, the House of Commons voted by 283 votes to 16 to end the trade in human slaves in all British territory. The principal opponent of the slave trade within Parliament and a leading figure in the diverse coalition of campaigners against the evil trade was a man named William Wilberforce. He worked closely with others building a broad coalition for the common good.

Wilberforce’s faith led him to campaign not only against slavery but also for wider moral reform of society and to his involvement in a range of organisations that are still going today.

In this publication (written for an April event with CCLA) Richard Turnbull introduces William Wilberforce.

A PDF is available here.

This article on Thatcher’s Monetarism and Timothy Lankester’s ‘Inside Thatcher’s Monetarism Experiment’ originally appeared at TheArticle

Sir Timothy Lankester has had a distinguished career of public service. He has served as Permanent Secretary at the Overseas Development Administration and the Department of Education; Director of the School of Oriental and African Studies; President of Corpus Christi College, Oxford; and Chairman of the Council, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. Inside Thatcher’s Monetarism Experiment (Policy Press, University of Bristol, 240 pp, £19.99) is about his time seconded as a member of the Administrative (not Government) Civil Service from H.M. Treasury to 10 Downing Street to serve as the Prime Minister’s Secretary for Economic Affairs, initially for James Callaghan (7 months) and then Margaret Thatcher (two and a half years).

The purpose of the book is to fill a gap in the economic history of the late 1970s and early 1980s and to show how Mrs Thatcher became infatuated with monetarism as an economic doctrine and implemented it as a laboratory experiment. However, this involved a vast cost of nearly one and a half million people becoming unemployed and thousands of firms going out of business. The author writes as a “disbelieving monetarist”: namely, someone who went along with monetarism because markets believed in it, even though he personally, in the best traditions of the UK Civil Service, did not.

While I am critical of Lankester’s understanding and assessment of monetarism, I thoroughly enjoyed reading the book. Its highlights are his relationship with the Prime Minister and colleagues, as well as his comments on the role and views of politicians, civil servants, special advisers, Bank of England officials, journalists, academic commentators and others.

He writes with admiration and affection for Mrs Thatcher, even though his view of the role and potential of government and the failures and imperfections of markets was very different from hers. “Mrs Thatcher and I got on well from day one,” is the way he describes his working relationship with the Prime Minister. He found her a kind and generous boss, including being invited regularly to the study for a drink in the early evening or supper in the flat with Dennis. He admired her in many ways, not least because, as he puts it, “she greatly valued those of us who worked most closely with her … there was a strong chemistry between us … the closeness of our relationship surprised me then and it surprises me to this day.” Yet he recognises that she had “a schizophrenic attitude to the Civil Service”, largely because of its ineffective delivery of services and its failure to get to grips with an increasingly bloated public sector.

The author makes clear that he approaches the subject with some personal history: he grew up in the lengthened shadow of the Great Depression, because his grandfather, a medical doctor, was forced to close his medical practice in 1930, leaving his father with no money to finish his schooling or attend university. In the Thatcher years, his wife’s family-run cotton textile manufacturing business in West Yorkshire was also forced to close.

This personal background and the great increase in unemployment from 1979 onwards leads him to a positively Augustinian confession: “Although only a minor player in this sad saga, I have always found it difficult to come to terms with the part I both wittingly and unwittingly played in it. … with hindsight, my admiration for her at a personal level, and my wish for her to succeed, made me work almost too hard on her behalf … I put to one side my reservations about monetarism and made myself see the world through her monetarist lens … I might have done more to push back on what Lawson would later call her ‘primitivist monetarism’ … this book is, in part, my attempt to achieve some kind of personal resolution.”

One issue which he addresses inadequately is why Mrs Thatcher, as someone proud of her training as a scientist, became so committed to the importance of monetary policy in controlling inflation. Her conviction was far from some beatific vision: it took the best part of a decade to develop.

When Mrs Thatcher became Prime Minister in May 1979, she inherited an economy described at the time as “the sick man of Europe” and suffering from “the British disease”: low productivity, high inflation, rising unemployment, stagflation, militant trade unions, strikes, and so on. The real pre-tax rate of return on trading assets in the UK manufacturing sector, which averaged around 10% in the 1960s, fell to 2.7% in 1974 and 1.9% in 1975; in textiles and metal manufacture, the real return was negative. Between 1974 and 1979, inflation averaged 16% annually, productivity was stagnant and the Government found it easier to borrow through the nationalised industries than on the Government’s own credit. The conventional Keynesian orthodoxy in terms of policy-making was also proving equally bankrupt: the long-run trade-off between unemployment and inflation had broken down; extra public spending or lower taxes could not be relied on to create more jobs; and a succession of incomes policies, voluntary and statutory, had proved ineffective in controlling inflation under previous Conservative and Labour governments.

After sitting around Edward Heath’s Cabinet table for four years, Mrs Thatcher had become convinced that if inflation was to be brought down, it needed some overall financial discipline. Subsequently, in 1976, while she was Leader of the Opposition, the IMF granted a loan to the UK (when it was effectively bust), but did so only on the condition that the Government would place ceilings on public sector borrowing and money supply growth (in the form of domestic credit expansion). In the academic world, distinguished scholars such as Hayek, Friedman, Johnson, Brunner, Walters and others had conducted extensive research which established that money supply growth affected prices in the long term, but in the short term, mainly output and employment. In addition, the explanation put forward by the Bundesbank and the Swiss National Bank to account for the success of their policies in controlling inflation was their control of money supply growth in their respective countries. All of this was in marked contrast to the part that money played in the intellectual approach of the UK Treasury, Bank of England and distinguished members of the then highly influential Cambridge University economics department.

The author deserves credit for recognising some of this, but then concludes with two observations: first, that the assumptions according to which monetarism should work were incorrect; and, second, that the cost of implementing the policy in increased unemployment was unacceptably high.

Lankester is certainly right to point out that the optimism of some of the early monetarists, myself included, was unfounded. Over the short term there was no systematic relationship between money supply growth and prices – the time lag was two years or longer. There were also differences of outcome when using different measures of the money supply. In addition, the regulatory environment in which monetary policy was conducted was constantly changing. Innovations such as the introduction of Competition and Credit Control, regulation by the “corset” and the abolition of exchange controls, made time series analysis difficult. However, the demand for money (the inverse of the velocity of circulation) has turned out to be stable over the longer term, such that central banks are able to control a measure of broad money which will affect prices after two year time lag. The best advice for a central bank is to aim for a steady growth of the money stock which is in line with the trend growth of money income.

The additional objection the author has to monetarism is its enormous cost in human suffering: namely, over 1 million jobs made redundant.

When she became Prime Minister in 1979, Mrs Thatcher made a point of honouring the pay settlements carried over from the “Winter of Discontent”, as well as the public sector pay awards recommended by the Clegg Commission, which the previous Government had instituted. Both were factors which inevitably led to some increase in unemployment, as was the new policy of switching revenues from high rates of income tax to a higher rate of VAT. However, over the next six years, unemployment in the UK continued to rise: from 6% to 12% of the labour force.

What is equally remarkable is that between 1980 and 1985 unemployment increased on average in all European Economic Community (EEC) countries — and by a large amount, from 5.8% to 11.2%. In Belgium, Italy and the Netherlands it rose above 12%. Even in Germany the unemployment rate more than doubled from 3.4% to 8.4%. Among the causes of this increase were the quadrupling of the oil price following the Iranian revolution and “sticky” real wages, because trade union bargaining power was strong, especially in public sector industries. But research has shown that fiscal tightening was not the cause. In other words, even without Mrs Thatcher’s policy revolution, executed by her Chancellor of the Exchequer Geoffrey Howe, unemployment would have risen significantly, if not doubled.

Lankester also acknowledges that research by Stephen Nickell and Jan van Ours had estimated that the “natural” rate of unemployment over these years for the UK — that is, the level at which the rate of inflation would remain stable, whether it was 0%, 2% or 10% — had risen from 3.8% (1969-73) to 7.5% (1974-89) and then to 9.5% (1981-86).

He concludes by recognising that there are positives from the growth of monetarism: that money does matter, in both analysis and policy, although we are not told how exactly that is so; that there is a “natural” rate of unemployment and so no sustainable trade-off between unemployment and inflation; that monetary policy is to be preferred to fiscal policy in the management of aggregate demand; and that unacceptable levels of unemployment must be tackled through micro-economic not macro-economic policies.

Should Mrs Thatcher have introduced an incomes policy which might have restrained wage increases over these years? Incomes policy had been introduced on numerous occasions since the early 1960s. The evidence from all incomes policies — whether introduced by Labour or Conservative governments and regardless of whether they were voluntary or statutory — is that they had no lasting impact on inflation. While they did initially lead to some wage restraint, this was subsequently undone, usually accompanied by strikes and industrial unrest.

Could the “British disease” of high inflation and high unemployment have been remedied without shock treatment? In principle, of course, it could — but in practice I very much doubt it. The most difficult challenge for the Thatcher Government in 1979-81 was to confront the economic malaise and the entrenched expectations of future inflation by trade unions, companies and the general public. This required a belief that the Government had a clear policy, that it would stick to the policy even though unemployment was rising, and that it would not change course. This it did. Its anti-inflationary policy was strengthened later by trade union reforms which reduced their power to disrupt the economy.

The irony of all this is that the 1981 Budget, which was roundly condemned by 364 economists because it put up taxes in order to reduce public borrowing (which was already greater than planned), actually marked the moment from which the UK economy recovered. It was a recovery that endured for the rest of the decade.

Sign up to receive blogs and book reviews via email

Brian Griffiths (Lord Griffiths of Fforestfach) is a Senior Research Fellow at Centre for Enterprise, Markets and Ethics (CEME) and Founding Chair of CEME (serving as Chair until 2023). Among other things he served at No. 10 Downing Street as head of the Prime Minister’s Policy Unit from 1985 to 1990 and Chair of the Centre for Policy Studies (CPS) from 1991 to 2001.

Photograph at top: Valentin Poleac; reproduced from Wikimedia Commons in accordance with a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International licence.