In March this year, I raised the question of whether the council tax premium on second homes constituted a solution to difficult problems – namely shortages of housing in some areas and straitened local authority finances – or was in effect a sumptuary law of sorts.

The Moral Issue

An important question was whether there was any ethical justification for the premium. One justification might be that investing earnings in a second home is in effect acting against the public interest, such that councils use the premium to discourage ‘hoarding’ of a scarce resource (housing). In response, however, some argue that such an outlook is naïve: second homes are often unsuitable for local residents, particularly first-time buyers, usually because of their age or character and cost, while in other cases, owners who renovate very old properties, far from diminishing the stock of habitable homes, actually add to it in the long run.

A further justification would be that the council tax premium helps to fund local services, yet critics argue that second home owners are thereby charged disproportionately for services – services that they do not even use all year round. As such, the rate charged appears to constitute supranormal taxation, legitimated by the additional wealth represented by possession of a second home. The suggestion here is that there is an ethical justification for taxation at a higher rate, as though wealth (or certain ‘lavish’ uses of it) is somehow immoral – a notion which historically lay behind certain sumptuary laws and which appears to be finding support at present. Recent discourse has suggested growing interest in new wealth taxes and there has been discussion of tax rises to target the wealthy in the forthcoming budget.

Interestingly, the government has not so far taken the view that wealth is unethical, the Chancellor having stated in the past that hers was now the party of wealth creation and written that wealth creation would be the defining mission of the government. While this was questioned from both sides of the political divide, as to whether it the proper role of government or even a desirable objective in itself (when perhaps wealth distribution might be considered a more pressing issue), there was clearly no suggestion on the Chancellor’s part that wealth was ‘unethical’.

The Economic Issue

On the economic aspects of the premium, I suggested that these would need to be observed before any conclusions could be drawn about their success as policy measures, and noted that historically, sumptuary laws, in addition to being difficult to assess, tend to have unintended consequences. The results of any council tax premium are likely to differ according to the area in which they take effect, as well as the manner in which they are implemented – and it is probably too early to make any kind of general judgement regarding their success or otherwise – but developments in one council are interesting.

A Local Case

It has been reported that Pembrokeshire County Council, which has the second highest number of second homes in Wales, has reduced its council tax premium on second homes twice in the space of 12 months. Having been increased to 50 per cent in 2017 and then 100 per cent in 2022, the rate has been reduced from a high of 200 per cent in 2024, to 150% and in recent weeks, to 125%.

It would appear that hundreds of second homes have been offered for sale in recent months, which would suggest that as a measure designed purely to increase housing stock, the premium could be considered successful. However, such properties have been slow to sell because prices are too high for local residents to afford. To date, therefore, the measure could not be said to address the lack of suitable available housing in the area, though there remains the question of market dynamics will lead to a longer term ‘correction’ of prices.

Unintended Consequences

It is evident that the premium as implemented has had unintended consequences. There is anecdotal evidence that the reduced number of holiday homes is having a negative impact on tourism in the area, Pembrokeshire being home to popular holiday destinations such as Tenby. Those in favour of the premium question its effects on tourism but any such decline in economic activity is likely to result in reduced tax revenues. It is of interest that a public consultation revealed a majority of non-second home owners (64 per cent) preferring a reduction in the premium on second homes.

Furthermore, the latest reduction in the council tax premium, effective from April 2026, will cost the council £1.4 million in potential income next year, which makes higher council tax increases for permanent residents more likely.

Conclusion

There are indeed serious challenges to be addressed by local authorities. Suitable, affordable housing is often in short supply and many are facing serious budgetary difficulties. A higher charge on second homes suggests itself as an obvious measure for addressing both but it is possible that the effects will not be as anticipated. A final assessment of the council tax premium would need to consider both broader moral questions and whether it accomplishes its economic aims. In areas where there is no strong tourist industry, perhaps a premium will have a minimal effect on local economic activity, or second homes offered for sale will not be out of reach of local buyers. Even where the policy shows signs of success, however, it is likely that other measures will be needed to address problems with housing supply. Where the desired outcomes fail to materialise, there remains the question of what grounds exist for a second home premium, beyond disapproval.

Talk given at the Danube Institute’s Conference, Budapest, 2nd October 2025. Brian also gave an interview about related topics.

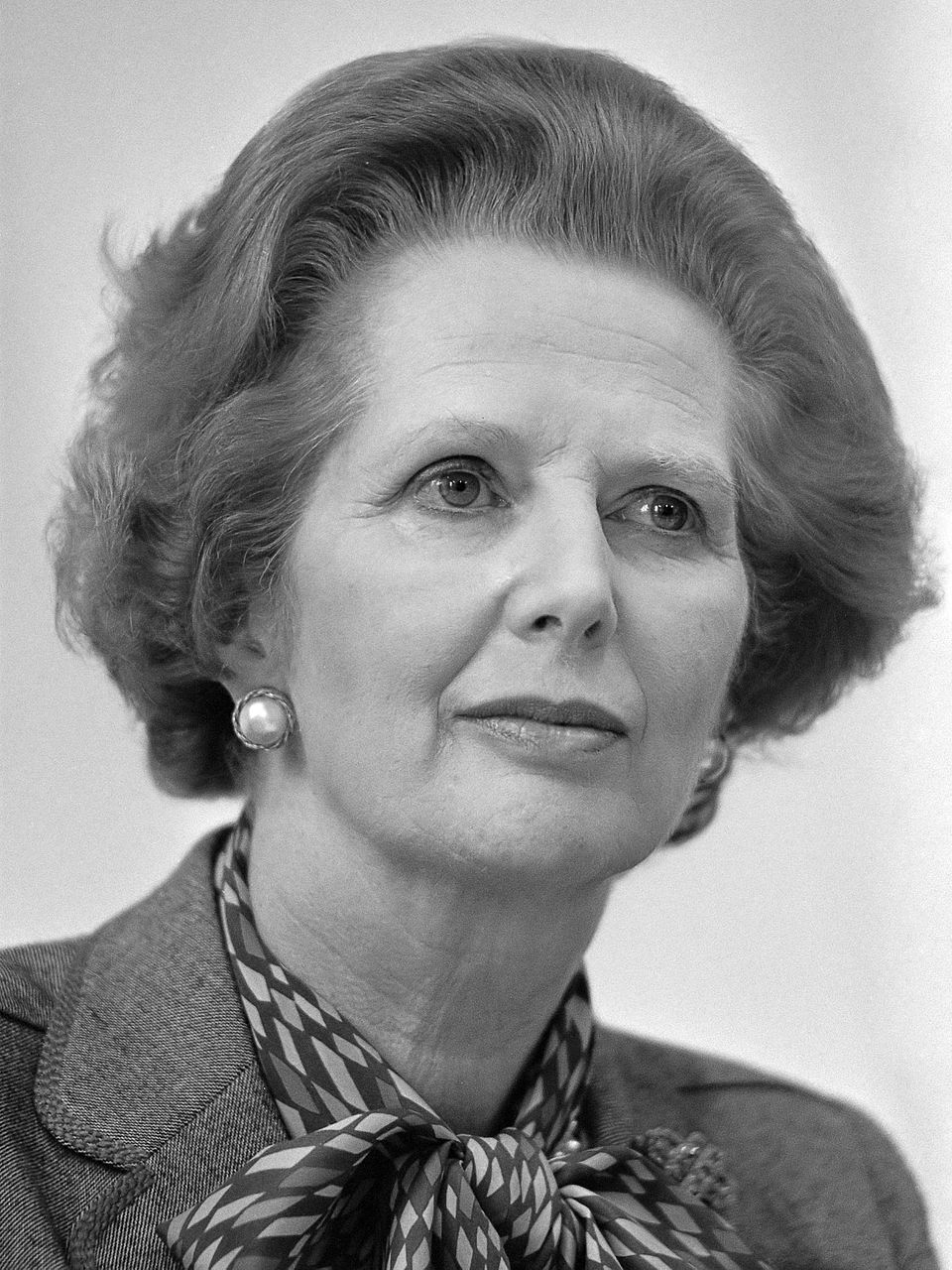

Mrs Thatcher became Prime Minister in May 1979 at a time when the UK economy was suffering from ‘the British disease’ and known as ‘the sick man of Europe’.

We had just emerged from the ‘Winter of Discontent’, during which there had been constant industrial disputes and strikes, many unofficial, uncoordinated and local. Some years earlier inflation had reached 27%. The Chancellor of the Exchequer Denis Healey had been forced to go, cap in hand to the IMF to avoid defaulting on our debts; no one would lend us money. We were bust. Inflation was still 13% in 1979 rising to 18% in 1980. Over the decade mismanagement of the economy and trade union militancy had led to the downfall of three governments: those of Wilson in 1970, Heath in 1974 and Callaghan in 1979. There was in British society a sense of helplessness, a feeling that the country had lost its way.

Mrs Thatcher set out to find practical remedies for the problems facing the British economy. She realised that not all could be achieved at once and I believe she thought of the response to the challenge in terms of three major steps.

First inflation must be defeated.

Second the size of the state in the economy must be reduced.

Third the market economy must be strengthened.

To start with it would be impossible to improve the standard of living without bringing inflation under control and establishing financial stability.

Inflation had been accompanied by rising unemployment which was not the Keynesian expectation. Inflation created uncertainty. It deterred business investment. It was hated by the public. Unexpected rises in the cost of living led to hardship with consequences such as higher interest rates which continued long after inflation had come down.

Although she was a practical politician, Mrs Thatcher was always interested in ideas. She was genuinely intellectually curious. She invited people into Number 10 from all sorts of different fields in order to explore ideas: historians, environmentalists, educationalists, theologians, architects and so on. And the field of economics was no exception. She valued meeting economists from abroad such as Milton Friedman, Fredrick von Hayek, Karl Brunner, Allan Meltzer as well as central bankers such as Otmar Emminger, and Karl Otto Pöhl (Bundesbank Presidents) and Fritz Leutwiler (Chairman of the Swiss National Bank).

Unlike many economists in the UK and senior officials at the Bank of England, these academic economists and practical central bankers saw inflation as a monetary phenomenon. They claimed they had achieved price stability in their countries because they had successfully controlled money supply growth, not because they had introduced prices and income policies. (Incidentally, money growth had been the traditional explanation for inflation in the writings of David Hume, Adam Smith, and Alfred Marshal – and even Keynes had spent six years in the 1920’s producing two large volumes entitled A Treatise on Money (1930), analysing the Quantity Theory of Money). This approach was also that of a small number of contemporary British economists such as Professor Alan Walters, whom she appointed as a special adviser based in No10, and Professor Harry Johnson, who held a joint chair of economics at the London School of Economics and the University of Chicago. By contrast these were not the views of the Bank of England or the UK Treasury which were still strongly influenced by Keynesian thought.

However, recognising that inflation was a monetary issue proved to be far easier than controlling the growth of money itself. How was it to be measured? How easily was it to control in the short term? How stable was the demand for money? How might it change when there were changes in the regulatory structure of the banking system, such as Competition and Credit Control 1971? Or external shocks to the system such as the Great Financial Crisis in 2008-9? These were difficult existential challenges for the Bank of England tasked with controlling money supply growth and financial stability. Controlling money supply growth however ensured that by 1986 retail price inflation had fallen to 3.4%.

Mrs Thatcher recognised that for the monetary policy to be successful, fiscal policy should accommodate monetary tightening and not work against it. This it did through the creation of a Medium Term Financial Strategy (the first ever for the UK Treasury) which linked targets for money supply growth to public sector deficits, public sector borrowing and the annual Budget. Alan Walters claimed that

It is difficult to exaggerate the importance of the commitment to the MTFS. It provided a frame of reference for all financial and economic policy. Never in the post-war history of Britain had the spending programs and the revenue and taxation consequences been so closely associated at the highest level of government decision making.

(p.83, Britain’s Economic Renaissance, OUP, 1986)

This framework provided effective fiscal discipline and led to the notorious 1981 budget. This was condemned by 364 UK academic economists in a letter The Times following a ‘round robin’ initiated by two Cambridge University professors, Frank Hahn and Robert Neild. For them, the uncomfortable fact was that this budget proved to be the turning point for Britain’s economic renaissance.

After having set out on a policy to introduce monetary discipline the second element in her policy was to reduce the scale of the state.

The case she made was that the state took too great a share national income, so government spending as a proportion of GDP needed to be reduced. The public sector borrowing requirement was crowding out private sector borrowing, so it, too, needed to be cut. In addition, state owned industries would be much better managed as commercial entities rather than being answerable to elected politicians in parliament.

This led to the policy of privatisation – steel, airlines, telecommunication, cars (Jaguar), gas, electricity, aerospace, petroleum, coal and so on. What was remarkable about privatisation was the way in which the policy, once shown to work in the UK, was adopted in the following two decades by so many countries throughout the world.

The scale of the state was also reduced by a housing policy which allowed the sale of council houses by local authorities to their tenants at considerable discounts, ranging from 33-50%, depending on their tenure. This meant a highly significant transfer of wealth and the ability of new house owners to pass their property on to their children.

The third element of Mrs Thatcher’s economic policy focused on strengthening the market economy.

In 1974 Mrs Thatcher and Keith Joseph had set up the Centre for Policy Studies to make the case for a market economy. By enabling prices to change and firms to enter or exit markets, they believed a market economy could achieve a more efficient allocation of resources than state planning, public ownership or government bureaucracy ever could.

They were also convinced that markets should be placed in the broader context of social responsibility. Many of the criticisms of the market economy were that it produced a culture of greed, individualism, and ‘dog-eat-dog’. They thought the creation of greater wealth through the market economy must be achieved alongside greater resources being available for those in need, whether due to ill-health, advanced age or deprivation.

Strengthening the market economy involved the abolition of rent controls, the abolition of foreign exchange controls, the removal of constraints on competition in banking and the London Stock Exchange – permitting foreign companies to enter London’s financial market – the removal of general controls over prices and wage growth and an almighty battle against trade unions to allow management to manage their firms without constant interruption from militant unions. This last required bitter battles in parliament and confrontations between police and protesters.

Her economic policy focused on wealth creation was part of a wider policy framework which increased parental choice and standards in education and training and increased expenditure in health and welfare. The social market economy provided the safety net for those unable to benefit directly from greater wealth. Standards in schools were improved. Scientific research dealing with technology and radical innovation was supported.

Thatcher’s economic policy had a coherence to it. It set out to achieve stable prices, reduce the size of the state and create a vibrant but socially responsible market economy. She succeeded in some areas: the importance of monetary policy in defeating inflation, reducing the size of government spending in GDP from 43% to 35%, strengthening an enterprise culture, extending home ownership and privatising state-owned industries. In others she did not succeed: the privatisation of water and railways, the imposition of the community charge for local services (the ‘poll’ tax) and increasing charitable giving.

There is one final point I would like to make.

While Mrs Thatcher engaged with the specific details of monetary policy or trade union legislation, this was in the service of an underlying moral world view. However, the idea that she had an ‘unidentified morality’, as Shirley Letwin has suggested, is somewhat misleading.

What she had was more than an intellectual framework or worldview. It is perhaps better understood by the German word Weltanschauung, which means not just an intellectual framework, but a driving force animating one’s being and generating a purpose for life’s work.

This for Mrs Thatcher was undoubtedly her Christian faith, something she made very clear in her speech to the General Assembly of the Church in Scotland on May 21st, 1988, in which she identified ‘three beliefs’ of the Christian faith.

First, that from the beginning man has been endowed by God with the fundamental right to choose between good and evil. Second, that we are made in God’s image and therefore we are expected to use all our own power of thought and judgment in exercising that choice; and further, if we open our hearts to God, he has promised to work within us. And third, that our Lord Jesus Christ the Son of God when faced with his terrible choice and lonely vigil chose to lay down his life that our sins may be forgiven. (Christianity and Conservatism, edited by The Rt Hon Michael Alison MP and David L. Edwards, Hodder & Stoughton, 1990, p.334)

She also spoke of ‘my personal belief in the relevance of Christianity to public policy’, recognising both the importance of the teaching of the Old and New Testaments and especially the importance of the family, on which ‘we in government base our policies for welfare, education and care’. (Speech by Mrs Thatcher to the opening of the General Assembly of the Church in Scotland, 21st May 1988, Christianity and Conservatism)

I believe you will never really understand Mrs Thatcher’s economics or politics unless you grasp her Judaeo-Christian worldview.

In conclusion, I believe this is ultimately the greatest legacy which Mrs Thatcher gives us today on the Centenary of her birth.

Brian Griffiths (Lord Griffiths of Fforestfach) is a Senior Research Fellow at Centre for Enterprise, Markets and Ethics (CEME) and Founding Chair of CEME (serving as Chair until 2023). Among other things he served at No. 10 Downing Street as head of the Prime Minister’s Policy Unit from 1985 to 1990 and Chair of the Centre for Policy Studies (CPS) from 1991 to 2001.

We have compiled some news, comment pieces and announcements that we hope our readers find interesting. In this instalment, there are stories relating to employment and inflation, artificial intelligence, taxation and carbon trading schemes:

Why British workers keep getting pay rises despite weak hiring (Financial Times)

Young hotel workers in Glasgow have negotiated a 10 per cent pay rise following a strike, an outcome that is perhaps indicative of a wider problem in the UK: pay awards remaining relatively high while employment slows down. With a weakening job market, such pay growth appears incompatible with the Bank of England’s target inflation rate of two per cent and there are concerns that inflation will become entrenched if households are now so accustomed to rising prices that they hold out for higher pay awards each year. Meanwhile, while they are reluctant to hire new starters or are keen to cut costs with less generous benefit packages, companies appear unwilling to reduce headline rates of pay when prices remain high and there is a widespread skills shortage

Faith in God-like large language models is waning (The Economist)

Enthusiasm for large language AI models appears to be in decline, with greater interest being shown in small language models. While no clear definition of the difference between the two exists, models that are trained using other AIs rather than having to crawl the web themselves, operate more quickly and with greater energy efficiency as a result of their more limited focus, and will run on in-house IT systems, appear to be more popular with companies, in part because of their lower cost but also because they can be adopted as bespoke models that focus on particular fields or functions.

This means that they can perform certain tasks well on industry specific data in a way that would not be cost effective for large language models. Better functionality and reliability, combined with a desire to see a return on any investment, have led to an expectation of growing demand for small language models at twice the rate of demand for all-purpose large language models. Should the trend continue, a more diverse landscape for artificial intelligence development is likely to emerge

We need to move on from the dreadful stamp duty system (The Times)

Stamp duty can be described as a tax that is complex, disincentivises purchases and house moves, reduces housing supply and increases rents. How would the lost revenue raised by stamp duty be replaced if the tax was abolished? Perhaps the answer is a reformed council tax charge based on the actual current value of property, without the current cap that ensures the most valuable properties are never charged at a rate that is more than three times that charged on the cheapest properties.

The problem with taxing the rich (FT)

The wealth of the super-rich has increased considerably since Forbes published its first list of billionaires in 1987 and there is a feeling that they ought to pay more tax. However, when in most developed countries, the largest shares of tax revenue are raised by sales and income taxes, and much of the wealth of the richest is invested in assets, taxing wealth is not straightforward.

Attempts to do so tend to lead to changes in behaviour. The history of wealth taxes suggests that they are of limited success and of the nations that have introduced them, few have retained them. Where they still exist, they raise little revenue.

While the UK has dismantled its ‘non-dom’ tax regime, other countries are seeking to attract the very wealthy – and for a government looking to extract more from the rich, there are numerous problems. How do we identify the very rich? Are they millionaires or billionaires? Are those whose homes have gone up in value and have more generous pensions than more recent generations the ‘very wealthy’? Such people are less mobile than the very richest and cannot move their wealth, so are easier to tax – but are they ‘super-rich’?

Some recommend a global asset tax on those with a total wealth of more than $1 billion, but asset taxes are very difficult to administer and enforce – and arguably discourage wealth accumulation and therefore economic activity. Others favour an ‘exit tax’ for those taking their wealth abroad. With ageing populations and increasing welfare costs, governments will continue to struggle with the question of whom to tax and how much, but while reform is needed, some argue that the narrative around tax and wealth needs to change.

Airlines fear carbon tax as flagship climate scheme develops holes (FT)

Corsia, the UN-backed Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation is running low on the carbon credits that airlines in participating countries (of which there are 130) must purchase (unless they procure sustainable aviation fuel instead, which is in very short supply). Such credits cannot be used by governments to meet climate goals once they have been used by airlines, so there is little incentive to sell them. Airlines are now concerned at the possibility that on reviewing the performance of the market-based scheme, the European Union will extend a carbon tax on flights within the bloc to external flights. Some organisations predict a continuing shortfall of available credits, and rising compliance costs. Iata, which represents airlines, is calling for greater availability of credits, while some countries have yet to commit to fully participating in Corsia, which is supposed to be mandatory for all members of the UN’s International Civil Aviation Organization:

My job interview with an AI recruiter: at least there was no small talk (The Telegraph)

What is it like to be interviewed by an AI bot and why are some companies conducting first round interviews using artificial intelligence? For companies, there is a saving of time now that they receive so many applications for each vacancy (some of which are produced by AI), but the results are ‘mixed’: for instance, artificial intelligence cannot distinguish between genuine responses and those being read from a script. Some interviewees found the questions to be more worthwhile and relevant to a role than those often asked by junior HR staff in a first round interview. Some – particularly technology enthusiasts – quickly found talking to a machine to be less awkward than expected. The technology is in its infancy but some version of it is likely to play an increasingly significant role in recruitment.

How We Found Our Callings

While all definitions of calling share in common the notion that work becomes meaningful within a person’s life, they differ on whether the source of the calling is internal, based on one’s own values, needs, and preferences, or external, based on either a calling from a higher power, a ‘transcendent summons,’ or a sense of fulfilling one’s destiny. Our own academic work together – which began with research on how the work of 9/11 victims was seen in the eyes of their close relations, and which has led to the publication of two books and several scholarly papers – feels secular in origin. We were both called to academia within a year of 9/11, when we were both living and working in New York City as management consultants, and although the call came from both a world in need of repair and from inside of us, it did not in our experience come from on high.

Religious and Secular Callings in the Financial Capital of the World

The first name on the New York City Medical Examiner’s list of casualties of the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks is that of Father Mychal Judge. He died carrying out his calling amid danger, praying to God over victims when he was killed by falling debris. Many people who died that day in a variety of uniforms were characterized as having lived out their callings, according to research we conducted. Most obviously, included are first responders like Jonathan Ielpi, a firefighter who followed his father into a profession in which he was ‘more concerned about others than he was about himself,’ Whether or not those callings were equally heroic, their origins were not always overtly religious.

Some callings sounded decidedly secular in origin, such as those of trader Frank Garfi, who ‘found a job that suited him precisely…fast-paced, demanding and as power-filled as an extreme sport,’ and trader Atsushi Shiratori, who was ‘so obsessed with the stock market that he once spent a two-week vacation in a day-trading salon. Sheryl Rosenbaum, who had known since her childhood visits to her father’s accounting office that ‘this was what she wanted to do,’ continued while she raised two young children of her own.

The History of Religious Callings

The notion of work as a calling has religious origins. As fellow management scholars Stuart Bunderson and Jeff Thompson detail in one of the foundational academic studies of calling toward work, the Protestant Reformation – and specifically the writings of Martin Luther – witnessed the transition of ‘calling’ from a narrow association with clergy work to a broader association with potentially any type of work. The important part was performing one’s work diligently and faithfully, laying the foundation for Max Weber’s notion of the Protestant Work Ethic.

This historical period also marked the culmination of a gradual transition of perceptions of work ‘from curse to calling,’ in the words of philosopher Joanne Ciulla. In Ancient Greece, work – especially manual labor – was seen as drudgery, punishment, and a distraction from one’s main goal of living a good life which was fully experienced in the life of the mind and certain types of leisure pursuits. When work becomes a calling, it becomes not a means to an end, but a meaningful end unto itself, a way to make a unique contribution to the world. The religious view of calling still has purchase in today’s conversations, in both scholarly writings and in the popular press. However, a different view has also emerged more recently that takes this same spirit into an explicitly non-religious context.

The Rise of Calling as a Secular (and Managerial) Concept

In another study, Thompson and Bunderson suggest that religious callings are typically ‘outside-in,’ emphasizing ‘destiny and duty’ and anchored in ‘societal obligations or an external summons.’ They contrast them with secular conceptualizations of calling that are typically ‘inside-out,’ emphasizing ‘passion and self-fulfillment’ and anchored in ‘internal preferences.’ Proponents of the former may express skepticism about whether the latter constitute ‘true’ callings. Proponents of the latter may doubt whether duty absent the passion to carry it out is sufficient to constitute a calling. Proponents of both tend to recognize that the best callings are those in which one feels to called in one’s heart to do what one is called by the world to do – or, in the words of theologian Frederick Buechner, ‘where your deep hunger and the world’s deep gladness meet.’

By the mid-1970s, when the field of management and organizational behavior was gaining traction as an academic discipline, scholars and other writers were increasingly considering work as a calling in a non-religious sense. For example, Studs Terkel’s famous compendium of interviews, Working, had a section titled, ‘In Search of a Calling’ that featured an editor, an industrial designer, and a nun-turned-massage therapist.

Jobs, Careers, and Callings

The presence of calling in management research – where we first encountered it – originated with a book by Robert Bellah and colleagues, Habits of the Heart. This book was not about callings or even work – the section on work was just over five pages long, the same length as a section on ‘leaving church’ – but rather about understanding how Americans’ private lives contributed to or detracted from their civic engagement. Yet, the writings about work proved to have a profound and outsized impact in codifying how ordinary people relate to their work. Based on interviews, the authors distinguished between work as a job or a means to make money, a career or a means to climb a career ladder, or a calling where work is a meaningful end in itself and ‘morally inseparable from [a person’s] life.’

These categories were further popularized and disseminated when they became the subject of study within organizational psychology by Amy Wrzesniewski and colleagues as one of three work orientations. In a pioneering study, Wrzesniewski found that, compared to a job or career orientation, employees who viewed their work as a calling reported greater satisfaction with work and with life and missed fewer days of work. As in Martin Luther’s view, any work could be viewed as a calling by the person holding it – even seemingly low-paid, low-status, and/or ‘dirty work,’ from hospital cleaners to zookeepers to administrative assistants. As a psychological construct, work orientation held that two people with the same position in an organization could come to view their jobs in wildly different ways: one a job, the other a calling.

What Do We Know Today?

Callings Can Be Sacred And/Or Secular

Academic research on work as a calling has exploded in the past two decades, which almost exactly mirrors a focus in the popular press on finding one’s calling through work. Reviews of calling research are quick to note the dual (if not dueling) perspectives on whether callings are sacred or secular. The neoclassical view of calling preferred by Bunderson and Thompson aims to build directly on the classical, religious view put forth by Luther and later Weber, defining calling as ‘that place in the occupational division of labor in society that one feels destined to fill by virtue of particular gifts, talents, and/or idiosyncratic life opportunities.’ The modern view, articulated by Dobrow and Tosti-Kharas, defines calling as ‘a consuming, meaningful passion people experience toward a domain, such as work.’

Both Kinds of Calling are Paths to a ‘Good Life’

A recent meta-analysis, of which Jen was a coauthor, examined more than 200 empirical studies of calling over the past 20 years, finding that experiencing a strong calling toward one’s work was related to a sense that one’s life was good. Whether a function of our work-centered modern culture, or of some jobs becoming objectively ‘better’ in post-industrial society, work is no longer necessarily a curse. The meta-analysis authors then looked at whether the type of calling, internal/modern or external/neoclassical, related to different types of well-being, hedonic (happiness or pleasure) or eudaimonic (meaningfulness, purpose, and self-realization). Both internal and external callings related to both types of well-being; however, internal callings were more strongly related to hedonic well-being, while external callings were more related to eudaimonic well-being.

What Does This Mean for Workers?

Callings Have Great Benefits…

In any case, possibly because we spend so much of our waking time at work, feeling that work has positive meaning has the potential to enhance our own and others’ flourishing. This is especially so with eudaimonic well-being, which can be supported by callings whether they are religious or secular in origin.

…And Can Come at Great Costs

Yet, the picture of how callings contribute to our lives is complicated, because they often demand sacrifices that can have deleterious effects on our well-being. The zookeeper study, which employed a neoclassical lens, portrayed calling as ‘a painfully double-edged sword.’ On one hand, a sense of calling elevated the importance and meaningfulness of work in subjects’ lives; on the other hand, it required sacrifices in the form of pay, long hours, and even social esteem. Further research supports that, regardless of whether callings are seen as secular or religious, they are intensely-felt and may involve a host of irrational behavior, from over-estimating one’s ability at work to ignoring the advice of trusted mentors to sacrificing money. A study of church ministers found that those with strongest callings had the hardest time disengaging from work at the end of the day, which in turn negatively affected their sleep quality and their vigor the next morning.

Callings are Worth Pursuing…

All of this is to say that, if we are fortunate enough to have a choice in the matter, we should choose wisely about whether to pursue work as a calling and which callings are worth pursuing. We should be realistic about what to expect of a calling, because even people who love their work may not be happy about the sacrifices and demands it requires every day. The cliché that if you ‘do what you love and you’ll never work a day in your life’ is often false, as anyone who has so much passion for their work can attest when the lines between their personal and professional lives blur to the point that they cannot escape work. We should also be mindful about whether some callings are ‘better’ than others. In our 9/11 research, which was based on close relations’ idealized reflections of how they wished their loved ones’ lives to have been, we found not only that a disproportionate share of victims were depicted as having worked at a calling but also that those callings which emphasized helping others and cultivating relationships with them were particularly admired. In those portraits of victims’ lives, their close relations found reasons for why even the most mundane or low status work – including that of receptionists and security guards and window washers – might have been worth loving.

…But Are Not a Panacea

As university professors, we counsel students not to feel undue pressure to ‘find their callings,’ especially as a surefire path to a perfect life. We teach them that some people are born knowing exactly what they were called to do and others search their entire lives in vain for a calling. They can’t control which one they might be, but it is within their control to carefully consider what pursuits are worth undertaking in a life worth living.

Jennifer Tosti-Kharas is the Camilla Latino Spinelli Endowed Term Chair and Professor of Management at Babson College.

Christopher Wong Michaelson is the Barbara and David A. Koch Endowed Chair in Business Ethics and Academic Director of the Melrose and The Toro Company Center for Principled Leadership at the University of St. Thomas and on the Business and Society faculty at NYU’s Stern School of Business.

Jen and Christopher are the authors of Is Your Work Worth It? How to Think About Meaningful Work (New York: Public Affairs, 2024) and The Meaning and Purpose of Work: An Interdisciplinary Framework for Considering What Work is For (London: Routledge, 2025).

The Centre for Enterprise, Markets and Ethics is pleased to announce the appointment of Revd Dr Philip Krinks as its new Director with effect from 6 October 2025.

Richard Turnbull, who served as Director until April 2025, will remain with the Centre as Director Emeritus.

Philip will bring a wealth of experience, knowledge and expertise in both business and theology. He is the ideal person to build on the solid platform laid by our Founding Director, Richard Turnbull in leading the work of the Centre.

I am deeply grateful for the opportunity to serve as Director. I am committed to building on the foundation laid by Lord Griffiths, Richard Turnbull and the whole CEME team, contributing a Christian perspective to economic debates.

Our vision has never been more relevant: a competitive market economy based on high ethical standards, where everyone can contribute with integrity to prosperity and the common good.

Over the coming months I look forward to engaging with CEME’s stakeholders and supporters – from economists, policymakers, and theologians to church leaders, entrepreneurs, and the business community – as together we advance this work.

Philip Krinks has a background in the academic study of enterprise, ethics and theology, in church ministry and in business consulting.

He read Classics and Philosophy at Magdalen College Oxford, and completed the management training programme at Citibank in London, before working in the Citi Foreign Exchange Sales & Trading business.

In 1998 he began a connection with Boston Consulting Group (BCG), which has lasted over 25 years. This included 5 years as Partner and Managing Director in their London Office, serving as Global Head of BCG’s Metals & Mining practice and undertaking pro bono projects with HM Treasury and the World Economic Forum.

In 2012 Philip left the BCG partnership to train for ministry in the Church of England. Subsequently, he served for 5 years as a Church of England Vicar, as Chaplain to the Bishop of Winchester and as Executive Director of the international social enterprise Pepal Foundation.

In addition to his Oxford MA, Philip holds an MBA from INSEAD, a PhD in Ethics from the University of London and an MA in Theology from King’s College London. He has published scholarly work on enterprise, ethics and theology.

I am delighted that Philip Krinks will succeed me as the Director of CEME. He will bring unique gifts and have unique opportunities. CEME was a remarkable vision that was in Lord Griffiths’ heart for many years. What a joy it was to bring that to fruition. We have built a great team and I know that they too will welcome Philip with open arms.”

Richard Turnbull is not an easy act to follow. But with a background of classics, philosophy, ethics, theology and the Church as well as practical experience in the world of consulting and financial trading, Philip Krinks is ideally placed to lead the Centre and I very much look forward to working with him.

The Centre for Enterprise, Markets and Ethics is pleased to announce an event in November 2025

Bishop of Oxford’s Office and the Church of England’s specialist on AI and tech within the Faith and Public Life Team

Tech Entrepreneur

We have compiled some news, comment pieces and announcements that we hope our readers find interesting. In this instalment, there are stories relating to free markets and patriotism, pharmaceuticals and markets, pay growth, consumer spending, public attitudes towards capitalism and free enterprise, the environment, and artificial intelligence and the stock market:

America’s new ‘patriotic’ capitalism (Financial Times)

The American government has bought a 15% share in MP Materials, a company that aims to produce rare earth minerals, and has guaranteed a ten-year price floor for its products. This is an interesting move in a country traditionally considered committed to free markets and is likely based on security concerns and the dearth of rare minerals supplies in the United States. It is perhaps also reflective of a wider shift in thinking within the administration, towards a more mercantilist outlook – at least with regard to security – particularly in view of China’s domination of the global supply of rare earth minerals, such that the government feels that in order to compete with China, something more than free market forces alone will be needed. An implication of this is the possible emergence of a new paradigm of ‘patriotic capitalism’ – a factor that investors may need to take into account when valuing assets in future.

Britain can’t win its fight against Big Pharma (The Spectator)

Recent reports surrounding the increased price of weight-loss injections and the Health Secretary’s claims regarding drug pricing reveal some interesting trends and phenomena in the market for pharmaceuticals. One is that negotiations between pharmaceutical companies and governments naturally involve a series of overlapping but not identical interests. Another is that NICE (the government health body) has been slow to adjust the figure that it is willing to spend on drugs for the National Health Service, which naturally leads to disputes with suppliers. In addition, the manufacture and supply of drugs is heavily regulated, which means that developments are slow and market principles are heavily skewed (particularly by certain forms of purchase arrangement). In addition, President Trump’s insistence that the United States should not be paying more for pharmaceuticals than other developed nations is likely to increase prices for other buyers. Where development costs are vast and prices appear likely to change, discounts for a relatively small buyer might be hard to secure, so is reform needed to the way in which prices are agreed and drugs purchased in the UK?

Britain’s jobs market has a slow puncture (The Economist)

With wage growth at around 5% per year and inflation above the Bank of England’s target (at 3.8%), the UK could arguably benefit from a softer labour market, but recent government measures increasing the minimum wage and lowering the threshold at which employers pay National Insurance, while also increasing the rate appear to press down on demand by increasing costs for employers, particularly when hiring lower-paid workers. So far there appears to have been no increase in redundancies, but vacancy rates are falling. Some employers are passing on costs to customers but others are simply not taking on new staff, not replacing leavers, or are making greater use of self-employed contractors.

UK pay growth close to four-year low (The Times)

According to figures from Incomes Data Research, average pay growth across the economy fell to 3% for July and August, an indication of an increase in available employees and slowing demand for workers:

UK should stop investing in carbon capture for power, government adviser says (Financial Times)

The Chief Executive of Octopus Energy (and government adviser as a member of the Industrial Strategy Advisory Council) has claimed that the UK government should stop investing in carbon capture technology for energy production. His argument is that in sectors where carbon abatement is difficult, carbon capture has a place, but for energy systems it makes more sense simply to burn gas unabated in order to reduce costs. As prices fall, green technologies such as heat pumps will become cheaper and will drive emissions reductions.

America’s middle-class spending power withers to historic low (The Telegraph)

According to Moody’s Analytics, households in the United States earning between $60,000 and $150,000 annually have seen the largest fall in their share of the national economy of any income group, as measured by consumer spending. The middle class now accounts for 28% of total consumer spending (down from 37% in 2002), while those in the top 10% of earners (earning over $250,000 per year) now account for 48%. Spending by those on the lowest incomes has fallen from 12% to 9%. All of this suggests that while globalisation increased overall wealth, middle class jobs in America suffered.

Image of Capitalism Slips to 54% in U.S. (Gallup)

Americans remain more favourably disposed towards capitalism than socialism, though the positive attitude towards captialism has slipped to 54% of those polled from a figure more typically around 60%. Negative attitudes towards socialism remain constant at around 57%, as do positive attitudes at around 39%. The outlook among Republicans is largely fixed, while among Democrats, the proportion viewing capitalism favourably has fallen to below half. Americans remain overwhelmingly positive about free enterprise (81% in favour) and small business (95%), but attitudes towards big business are in decline, with 37% viewing it positively and 62% negatively.

What if the AI stockmarket blows up? (The Economist)

Have investors over-reacted to the capacity of AI to increase productivity? Are we witnessing an investment bubble based on hype over the technology’s capacity to transform the economy? Perhaps so, if returns have so far been disappointing relative to the scale of investment. Nevertheless, there have been numerous bubbles in history surrounding technologies that went on to become essential parts of everyday life (such as electric lighting). The question, perhaps, surrounds the nature of any investment bubble surrounding AI and what kind of crash – if any – might follow. Perhaps the significant determining factors are what sparks the exuberant investment (new technology or perhaps government regulations or taxes), the scale and durability of the capital deployed, the use that the invested capital is put to (whether it results in something useful to the economy more widely) and who bears the losses when the bubble bursts. On these criteria, the apparent AI bubble seems relatively modest at present – though the scale of expenditure could be enormous if one considers the need to invest in data centres to make further development possible. It is also true that politicians have fuelled investment begun by technological innovation. Perhaps the most worrying question is where the losses of any crash might fall: on tech companies and institutional investors, certainly, but with the wealth of richer households heavily exposed to the stock market, as is the case in the United States at present, there are serious implications for an economy whose growth has of late been driven to a significant degree by consumer spending on the part of the wealthy.

The Centre for Enterprise, Markets and Ethics is pleased to announce the appointment of Professor Philip Booth as Academic Advisor and Senior Research Fellow. He was previously an Associate Fellow. As part of his new role, he will be working for CEME one day a week.

Philip Booth is professor of Catholic Social Thought and Public Policy at St. Mary’s University, Twickenham (the U.K.’s largest Catholic university) and Director of Policy and Research at the Catholic Bishops’ Conference of England and Wales. He is also Senior Research Fellow and Academic Advisor to the Centre for Enterprise, Markets and Ethics.

Previously, Philip was academic and research director at the Institute of Economic Affairs from 2002 to 2016 and senior academic fellow there from 2016 to 2021. He has worked for the Bank of England and as associate dean of Bayes (formerly Cass) Business School. He held the positions of Director of Research and Public Engagement; Dean of the Faculty of Education, Humanities and Social Sciences; and Director of Catholic Mission at St. Mary’s.

Philip has written widely on investment, finance, social insurance, and pensions, as well as on the relationship between Catholic social teaching and economics. He curates the website: www.catholicsocialthought.org.uk.

His books include Catholic Social Teaching and the Market Economy; Catholic Social Thought the Market and Public Policy; The Road to Economic Freedom; Verdict on the Crash; and Christian Perspectives on the Financial Crash.

He is a fellow of the Royal Statistical Society, a fellow of the Institute of Actuaries, and an honorary member of the Society of Actuaries of Poland.

He has a B.A. in Economics from the University of Durham and a Ph.D. in Real Estate Finance from City University.

We have compiled some news, comment pieces and announcements that we hope our readers find interesting. In this instalment, there are stories relating to artificial intelligence, free trade, economic growth, employment, post-disaster reconstruction and the environment:

A new wave of clean-energy innovation is building (The Economist)

While the Trump administration has withdrawn subsidies from wind and solar power generation, there are reasons to expect innovation in green technology to continue in the United States. New energy generation technologies reduce dependence on foreign imports, which makes them popular, while the bill withdrawing subsidies from wind and solar leaves support in place for other forms of green technology, such as linear generators, geothermal energy, fuel cells and new types of nuclear power. In addition, tech companies struggling to find sufficient energy to power their data centres are investing in energy solutions, usually with a ‘green mindset’, and in some cases favour the development of small modular nuclear reactors:

https://www.economist.com/business/2025/08/14/a-new-wave-of-clean-energy-innovation-is-building

‘You will have AI friends’: Character.ai bets on companionship chatbots (Financial Times)

The chatbot maker Character.ai is a leader in creating persona-based chatbots for users to interact with. Popular with young users and with the average user spending 80 minutes per day on the app, over a third claim to have discussed important matters with the chatbot or to have transferred social skills practised on the platform to real life situations. The CEO claims that the chatbot characters will not replace ‘real friends’ but that most people will have ‘AI friends’ in the future. The company faces a number of legal suits from parents who claim that their children have suffered real harms from interacting with the platform:

https://www.ft.com/content/0bcc4281-231b-41b8-9445-bbc46c7fa3d1

How America’s AI boom is squeezing the rest of the economy (The Economist)

The development of AI is thought to be responsible for around 40% of America’s GDP growth, in spite of the sector only accounting for a few per cent of national GDP itself. Given the heavy costs of infrastructure and the rate of development, tech companies are increasingly turning to borrowing to fund their projects. As this drives the costs of energy and borrowing upwards, a slow-down in other sectors more sensitive to such price changes appears to be occurring: housebuilding, non-AI business and overall consumption are sluggish, and wage growth is weak. If a reallocation of economic resources is underway, then what will be the wider consequences be for an apparently otherwise flat economy, increasingly dependent on AI investment, should the AI boom turn to bust?

UK vacancies for entry-level jobs hit five-year low (The Times)

Vacancies for entry-level jobs in the UK have dropped to their lowest level since 2020, accounting for around a fifth of the overall market. Contract work has risen by 22 per cent since April, as organisations opt to hire workers on temporary rather than permanent contracts. Vacancies in healthcare and nursing have also suffered significant declines since April, perhaps following changes to employers’ National Insurance contributions and increases in the minimum wage:

The chancellor needs a vision. Can she find it in ‘Abundance’? (The Times)

With the difficulties faced by the Chancellor, should the previously touted vision of ‘Securonomics’, now quietly abandoned, be replaced by a focus on ‘abundance’, whereby the economy is flooded with freedom to operate and constraints on development in housing, infrastructure and energy are removed? If the government seeks to pursue economic growth, then a change in mindset with regard to regulation might well be necessary:

The $140 Billion Failure We Don’t Talk About (The New York Times)

Following Hurricane Katrina, the Federal government invested a sum for reconstruction that, when adjusted for inflation, was more than was spent on the World War II Marshall Plan to rebuild Europe or for the rebuilding of Lower Manhattan after terrorist attacks of 9/11 – yet New Orleans remains smaller, poorer and more unequal than before the storm, lacking basic services and a major economic engine beyond the tourism industry. It seems that the reconstruction lacked any clear vision or accountability, and ended up focusing on replacing what was lost rather than improvement or greater resilience in the future. The outcomes for New Orleans suggest that recovery programmes need to be radically rethought, with accountability, resilience and equity at the centre:

https://www.nytimes.com/2025/08/27/opinion/new-orleans-katrina-funds.html

Born in New York City and raised in the UK, Rabbi Benjy Morgan spent 14 years studying in the top Rabbinic training academies in the world. He is the Chief Executive Officer of the Jewish Learning Exchange (JLE), a London-based organisation which aims to teach Judaism’s relevance and deeper meaning to 21st-century Jewish youth and young professionals, so as to enable them to connect with one another and make informed life decisions.

What Elements of Covenant in Genesis are Relevant to Politics in Western Democracies Today?

The book of Genesis offers a radical theological idea: that God enters into relationship with humanity not as a distant ruler, but as a partner. The first covenants—those made with Noah and with Abraham—are not commands from above but invitations to moral responsibility and dialogue.

The Noahide covenant is universal. After the flood, God makes a commitment to all of creation, establishing a foundational moral framework for society—emphasizing justice, the sanctity of life, the rule of law, and the dignity of every human being. It affirms that every human life has value because we are all created in the image of God.

The Abrahamic covenant introduces particularity—not for the sake of privilege, but to take on a role of moral responsibility. Abraham is not given a detailed system of laws, but a calling: to build a life and legacy grounded in faith, justice, and service to others. His journey begins the intertwining of religious faith with historical purpose.

For modern democracies, this theology warns against treating politics as ultimate. The state is not God. Power must be tempered by ethical principles. A covenantal worldview calls for shared responsibility even amidst difference. It teaches that society thrives when citizens see themselves as morally bound to one another.

Is Reference to the Sacred Necessary when Using the Word ‘Covenant’?

Yes. A covenant is not just a contract between individuals—it is a three-way relationship that includes a higher moral authority. It reflects a belief that our obligations are not only to each other, but to something greater.

Even when used in secular contexts, the word ‘covenant’ carries with it echoes of this deeper meaning. It implies that life is not merely about personal freedom, but about purpose. It affirms that we are not self-made, but called. In Jewish thought, this is why obligation is often seen as more important than autonomy: because it roots us in a shared moral vision.

Trying to speak of covenant without reference to the sacred is like describing a flame without fire. It’s not necessarily about organized religion, but about the idea that life has meaning, that we are responsible, and that we are part of a larger story.

What are the Vital Elements of a Covenantal Economy?

A covenantal economy is more than just an ethical marketplace. It is built on the understanding that land, wealth, and even time are not ours absolutely—they are entrusted to us. We are stewards, not owners.

Several key principles in Jewish law illustrate this:

A covenantal economy, then, asks a different set of questions: not just ‘What can I earn?’ but ‘What do I owe?’ Not just ‘What is profitable?’ but ‘What is just?’ It places generosity, dignity, and long-term stewardship at the heart of economic life.

How Understood is ‘Covenant’ Today, and How Can it be Made More Accessible?

Today, the term ‘covenant’ is not widely understood. Yet the longing for what it represents is everywhere: people crave connection, purpose, and belonging. The challenge is to give this ancient idea modern language and relevance.

In Jewish thought, covenant is how a people survives history—not through force, but through faithfulness. It’s a structure of hope: the belief that the future is not predetermined, but shaped by the commitments we make.

We can make the idea of covenant more accessible by:

Ultimately, covenant means that each person matters. Our choices matter. And the future depends on the values we choose to uphold together.

Conclusion

Ours is an age, not of cynicism but of seeking. People are no longer content with fragments; they long for wholeness. They search for meaning that binds the personal to the collective, the moral to the spiritual, the ‘I’ to the ‘we.’

Covenant speaks precisely to this moment. It tells us that freedom is not isolation, but responsibility. That identity is not exclusion, but connection. That truth is not imposed, but shared. In a world crying out for belonging, covenant is the music of relationship—the sacred bond that turns individuals into communities and life into a journey of purpose. We are not alone. We are bound—by trust, by hope, by a story we tell together.