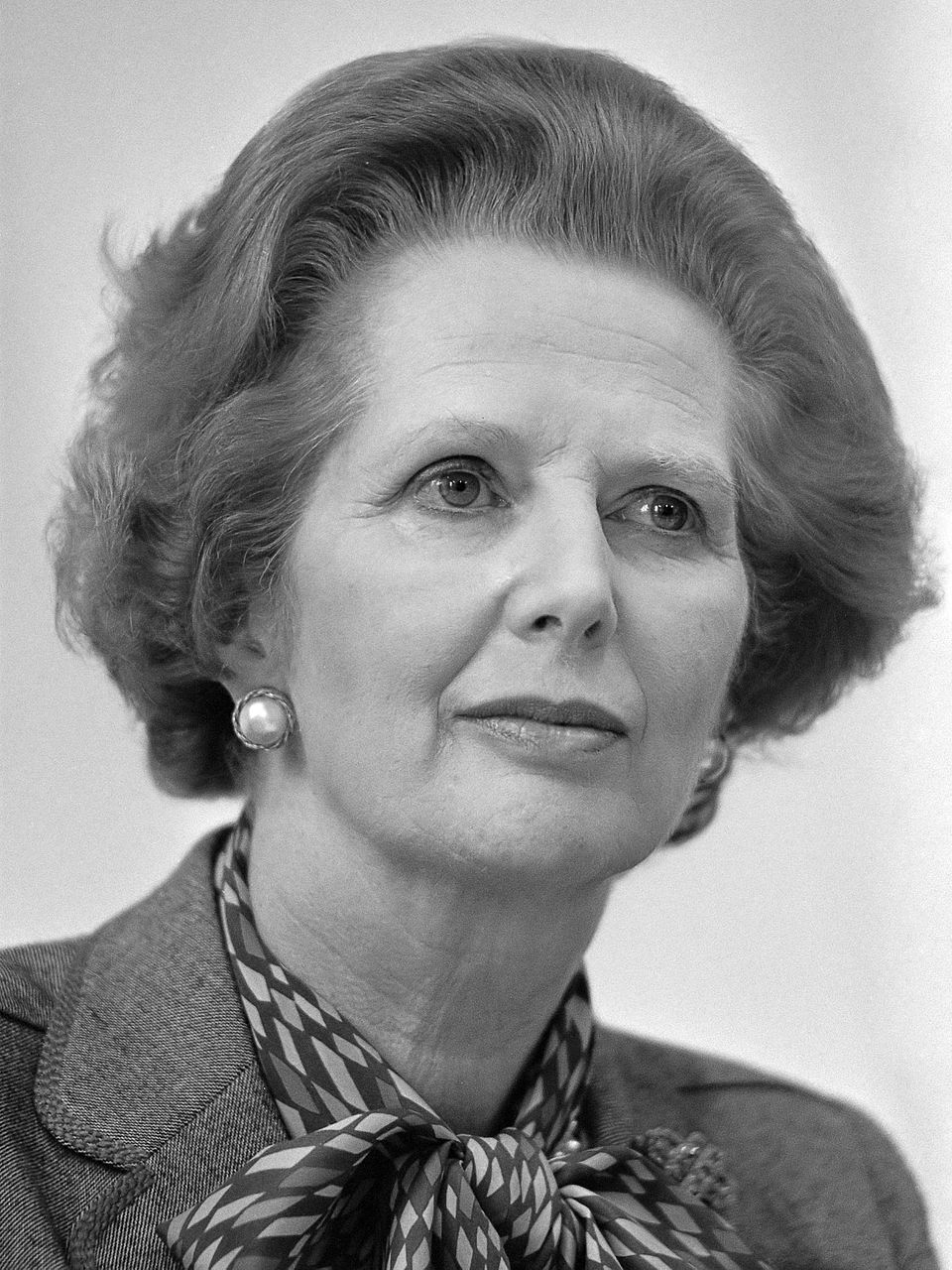

Brian Griffiths: Margaret Thatcher – A Life & Legacy: Mrs Thatcher’s Economic Policy

Talk given at the Danube Institute’s Conference, Budapest, 2nd October 2025. Brian also gave an interview about related topics.

Mrs Thatcher became Prime Minister in May 1979 at a time when the UK economy was suffering from ‘the British disease’ and known as ‘the sick man of Europe’.

We had just emerged from the ‘Winter of Discontent’, during which there had been constant industrial disputes and strikes, many unofficial, uncoordinated and local. Some years earlier inflation had reached 27%. The Chancellor of the Exchequer Denis Healey had been forced to go, cap in hand to the IMF to avoid defaulting on our debts; no one would lend us money. We were bust. Inflation was still 13% in 1979 rising to 18% in 1980. Over the decade mismanagement of the economy and trade union militancy had led to the downfall of three governments: those of Wilson in 1970, Heath in 1974 and Callaghan in 1979. There was in British society a sense of helplessness, a feeling that the country had lost its way.

Mrs Thatcher set out to find practical remedies for the problems facing the British economy. She realised that not all could be achieved at once and I believe she thought of the response to the challenge in terms of three major steps.

First inflation must be defeated.

Second the size of the state in the economy must be reduced.

Third the market economy must be strengthened.

To start with it would be impossible to improve the standard of living without bringing inflation under control and establishing financial stability.

Inflation had been accompanied by rising unemployment which was not the Keynesian expectation. Inflation created uncertainty. It deterred business investment. It was hated by the public. Unexpected rises in the cost of living led to hardship with consequences such as higher interest rates which continued long after inflation had come down.

Although she was a practical politician, Mrs Thatcher was always interested in ideas. She was genuinely intellectually curious. She invited people into Number 10 from all sorts of different fields in order to explore ideas: historians, environmentalists, educationalists, theologians, architects and so on. And the field of economics was no exception. She valued meeting economists from abroad such as Milton Friedman, Fredrick von Hayek, Karl Brunner, Allan Meltzer as well as central bankers such as Otmar Emminger, and Karl Otto Pöhl (Bundesbank Presidents) and Fritz Leutwiler (Chairman of the Swiss National Bank).

Unlike many economists in the UK and senior officials at the Bank of England, these academic economists and practical central bankers saw inflation as a monetary phenomenon. They claimed they had achieved price stability in their countries because they had successfully controlled money supply growth, not because they had introduced prices and income policies. (Incidentally, money growth had been the traditional explanation for inflation in the writings of David Hume, Adam Smith, and Alfred Marshal – and even Keynes had spent six years in the 1920’s producing two large volumes entitled A Treatise on Money (1930), analysing the Quantity Theory of Money). This approach was also that of a small number of contemporary British economists such as Professor Alan Walters, whom she appointed as a special adviser based in No10, and Professor Harry Johnson, who held a joint chair of economics at the London School of Economics and the University of Chicago. By contrast these were not the views of the Bank of England or the UK Treasury which were still strongly influenced by Keynesian thought.

However, recognising that inflation was a monetary issue proved to be far easier than controlling the growth of money itself. How was it to be measured? How easily was it to control in the short term? How stable was the demand for money? How might it change when there were changes in the regulatory structure of the banking system, such as Competition and Credit Control 1971? Or external shocks to the system such as the Great Financial Crisis in 2008-9? These were difficult existential challenges for the Bank of England tasked with controlling money supply growth and financial stability. Controlling money supply growth however ensured that by 1986 retail price inflation had fallen to 3.4%.

Mrs Thatcher recognised that for the monetary policy to be successful, fiscal policy should accommodate monetary tightening and not work against it. This it did through the creation of a Medium Term Financial Strategy (the first ever for the UK Treasury) which linked targets for money supply growth to public sector deficits, public sector borrowing and the annual Budget. Alan Walters claimed that

It is difficult to exaggerate the importance of the commitment to the MTFS. It provided a frame of reference for all financial and economic policy. Never in the post-war history of Britain had the spending programs and the revenue and taxation consequences been so closely associated at the highest level of government decision making.

(p.83, Britain’s Economic Renaissance, OUP, 1986)

This framework provided effective fiscal discipline and led to the notorious 1981 budget. This was condemned by 364 UK academic economists in a letter The Times following a ‘round robin’ initiated by two Cambridge University professors, Frank Hahn and Robert Neild. For them, the uncomfortable fact was that this budget proved to be the turning point for Britain’s economic renaissance.

After having set out on a policy to introduce monetary discipline the second element in her policy was to reduce the scale of the state.

The case she made was that the state took too great a share national income, so government spending as a proportion of GDP needed to be reduced. The public sector borrowing requirement was crowding out private sector borrowing, so it, too, needed to be cut. In addition, state owned industries would be much better managed as commercial entities rather than being answerable to elected politicians in parliament.

This led to the policy of privatisation – steel, airlines, telecommunication, cars (Jaguar), gas, electricity, aerospace, petroleum, coal and so on. What was remarkable about privatisation was the way in which the policy, once shown to work in the UK, was adopted in the following two decades by so many countries throughout the world.

The scale of the state was also reduced by a housing policy which allowed the sale of council houses by local authorities to their tenants at considerable discounts, ranging from 33-50%, depending on their tenure. This meant a highly significant transfer of wealth and the ability of new house owners to pass their property on to their children.

The third element of Mrs Thatcher’s economic policy focused on strengthening the market economy.

In 1974 Mrs Thatcher and Keith Joseph had set up the Centre for Policy Studies to make the case for a market economy. By enabling prices to change and firms to enter or exit markets, they believed a market economy could achieve a more efficient allocation of resources than state planning, public ownership or government bureaucracy ever could.

They were also convinced that markets should be placed in the broader context of social responsibility. Many of the criticisms of the market economy were that it produced a culture of greed, individualism, and ‘dog-eat-dog’. They thought the creation of greater wealth through the market economy must be achieved alongside greater resources being available for those in need, whether due to ill-health, advanced age or deprivation.

Strengthening the market economy involved the abolition of rent controls, the abolition of foreign exchange controls, the removal of constraints on competition in banking and the London Stock Exchange – permitting foreign companies to enter London’s financial market – the removal of general controls over prices and wage growth and an almighty battle against trade unions to allow management to manage their firms without constant interruption from militant unions. This last required bitter battles in parliament and confrontations between police and protesters.

Her economic policy focused on wealth creation was part of a wider policy framework which increased parental choice and standards in education and training and increased expenditure in health and welfare. The social market economy provided the safety net for those unable to benefit directly from greater wealth. Standards in schools were improved. Scientific research dealing with technology and radical innovation was supported.

Thatcher’s economic policy had a coherence to it. It set out to achieve stable prices, reduce the size of the state and create a vibrant but socially responsible market economy. She succeeded in some areas: the importance of monetary policy in defeating inflation, reducing the size of government spending in GDP from 43% to 35%, strengthening an enterprise culture, extending home ownership and privatising state-owned industries. In others she did not succeed: the privatisation of water and railways, the imposition of the community charge for local services (the ‘poll’ tax) and increasing charitable giving.

There is one final point I would like to make.

While Mrs Thatcher engaged with the specific details of monetary policy or trade union legislation, this was in the service of an underlying moral world view. However, the idea that she had an ‘unidentified morality’, as Shirley Letwin has suggested, is somewhat misleading.

What she had was more than an intellectual framework or worldview. It is perhaps better understood by the German word Weltanschauung, which means not just an intellectual framework, but a driving force animating one’s being and generating a purpose for life’s work.

This for Mrs Thatcher was undoubtedly her Christian faith, something she made very clear in her speech to the General Assembly of the Church in Scotland on May 21st, 1988, in which she identified ‘three beliefs’ of the Christian faith.

First, that from the beginning man has been endowed by God with the fundamental right to choose between good and evil. Second, that we are made in God’s image and therefore we are expected to use all our own power of thought and judgment in exercising that choice; and further, if we open our hearts to God, he has promised to work within us. And third, that our Lord Jesus Christ the Son of God when faced with his terrible choice and lonely vigil chose to lay down his life that our sins may be forgiven. (Christianity and Conservatism, edited by The Rt Hon Michael Alison MP and David L. Edwards, Hodder & Stoughton, 1990, p.334)

She also spoke of ‘my personal belief in the relevance of Christianity to public policy’, recognising both the importance of the teaching of the Old and New Testaments and especially the importance of the family, on which ‘we in government base our policies for welfare, education and care’. (Speech by Mrs Thatcher to the opening of the General Assembly of the Church in Scotland, 21st May 1988, Christianity and Conservatism)

I believe you will never really understand Mrs Thatcher’s economics or politics unless you grasp her Judaeo-Christian worldview.

In conclusion, I believe this is ultimately the greatest legacy which Mrs Thatcher gives us today on the Centenary of her birth.

Brian Griffiths (Lord Griffiths of Fforestfach) is a Senior Research Fellow at Centre for Enterprise, Markets and Ethics (CEME) and Founding Chair of CEME (serving as Chair until 2023). Among other things he served at No. 10 Downing Street as head of the Prime Minister’s Policy Unit from 1985 to 1990 and Chair of the Centre for Policy Studies (CPS) from 1991 to 2001.